The tuatara isn’t actually a lizard. It’s the last survivor of a 250 million year old group of reptiles that mostly went extinct with the dinosaurs. It doesn’t have a penis, and ironically, that’s made it a linchpin for understanding how penises evolved in vertebrates.

The tuatara’s penis-less state stands out because the other descendants of the first scaly animals to evolve shelled eggs that require internal fertilisation — called amniotes — do have penises, and those penises are wildly diverse.

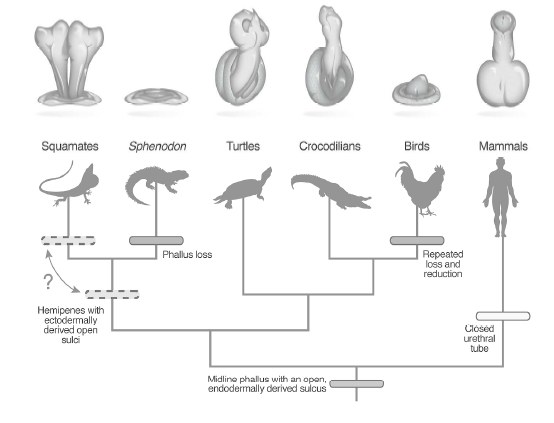

Mammals use cylinders of inflatable erectile tissue. Turtles have a terrifyingly large organ that layers inflatable tissues on top of a stiff tongue-shaped shovel. Crocodilian penises are permanently stiff, pushed out by muscles and pulled back in by bungee-cord tendons. Snakes and lizards have two, which are stored inside-out in their bodies and inflated into females. And then there’s the high-speed flexible madness of waterfowl like ducks.

For years, those anatomical differences fed a debate about penis evolution. The tuatara has a lot of features biologists think were also found in the earliest amniotes. If “no penis” was one of those ancient characteristics, then the wildly different shapes of lizard, crocodile, and mammal penises could have evolved independently. But other biologists argued that penises had evolved once in early amniotes and changed in unique ways within each group over time. If that view were true, the tuatara would be one of the rare groups of animals that had lost their penis.

A study released in yesterday’s Biology Letters adds a new piece to the puzzle, lending support to the idea that the amniote penis evolved only once.

The very best way to resolve the argument was to take a close look at some tuatara embryos. If the embryos never developed any of the early stages for growing a penis, it would support the idea that penises had evolved more than once. But if they started to grow a penis that was later reabsorbed, it would suggest that all living amniotes inherited a penis-building blueprint from an ancient ancestor. For Martin Cohn and his team of developmental biologists at the University of Florida, it was also one of the last remaining steps in a years-long project to track genital development across vertebrates.

There was just one problem: the tuatara is an endangered species that breeds incredibly slowly: it takes a tuatara about as long as a human to become sexually mature, and females only lay a clutch of eggs every 2 to 5 years. As a result, every one of their eggs is precious and tightly controlled by the New Zealand government.

100 Year Old Embryos

Getting fresh tuatara eggs was going to be impossible. But Thomas Sanger, a postdoctoral associate in Cohn’s lab, thought there might be another way to attack the problem.

Before he had moved to Florida, Sanger had worked at Harvard University. And he’d learned that Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology owned a historic collection of slides that included a few tuatara embryos.

The slides had belonged to Charles Minot, a comparative embryologist who’d amassed an enormous number of specimens from around the world before his death in 1914. In 1909, he had received four tuatara embryos, which he sliced thin and mounted on a series of 82 slides. “It was a great wealth of historical information that we could use for our modern questions,” said Sanger.

But first, he had to track down the right slides. A little detective work showed that one of the four embryos, specimen 1491, was collected at the same developmental stage where they saw the earliest hints of penis development in other amniotes. If the tuatara embryo had the same genital swellings as snakes or alligators at a similar stage, it would be evidence that the animal had the potential to grow a penis.

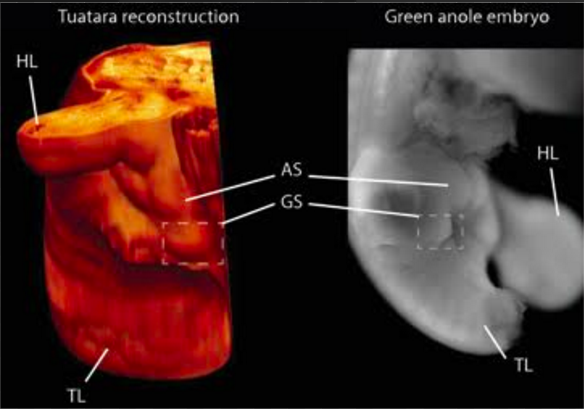

The swellings, if they existed, would be visible on the surface of the embryo. But this particular embryo had already been sliced up like a loaf of bread. If they were going to answer their question, they needed to reassemble the loaf. Working with Marissa Gredler, then a graduate student in the lab, Sanger photographed every undamaged section on each slide and used an imaging program to stack them, creating a three-dimensional model of the tuatara embryo.

“The slides had been in storage for most of the 20th century,” Sanger said. “so some slides had gone missing. They were also pretty dusty and beat up, and required some careful cleaning before I could photograph them. But for specimens that were over 100 years old, the histological quality was amazing.”

Tiny Genital Swellings in 3D

Some of the lost slides included the left half of specimen 1491. But out of the slides that were left, Sanger and Gredler were able to build a virtual 3D model of the embryo showing its tail, right leg, and underside. Clear as day, there were bumps on the tuatara that corresponded to the anal and genital swelling of other amniotes: structures that in animals like lizards and turtles grow and fuse to eventually form the rim of the cloaca and the penis.

Key for diagram: HL = hindlimb | TL = tail | AS = anal swelling | GS = genital swelling. From Sanger, Gredler and Cohn 2015

The implication is that male tuataras start to grow a penis as an embryo, but reabsorb it before they’re ready to hatch. That means every single amniote lineage has the wherewithal to make a penis. And that suggests a penis is an ancient amniote trait that has diversified in many amazing ways over time.

Penis diversification within the amniotes. From Sanger, Gredler and Cohn 2015

But since this project is based on observations of just one half of one embryo, it leaves a lot of questions about the tuatara’s reproductive development unanswered. “The fact that the penis shares a developmental pathway with the limbs might be a real constraint that keeps basic genital development in all amniotes,” said Patricia Brennan, who studies the effects of sexual conflict on genital anatomy at Mount Holyoke College. “It would be nice to see a follow up with a whole tuatara embryo.” Or ideally, multiple embryos at different stages of development.

That’s because one embryo represents just a single frame of the entire developmental drama. It can only tell us what’s happening at one moment in time. It cannot answer questions about how long a tuatara penis grows before it destroys itself, or whether it is built on the single-shaft model like most other amniotes or shares the split-shaft form of the snakes and lizards that are its closest cousins.

The Cohn lab has even seen this sort of penis disappearing act before: in birds like chickens, penis growth starts normally in the embryo, but the organ is eventually destroyed by an expanding wave of self-destructing cells. “It would be cool to test whether the regression of genital buds in the tuatara occurs the same way as it does in birds” said Gredler.

[Gillingham et al. 1995 [Nelson et al. 2010 [Jones and Cree 2012 [Herrera et al 2013 [Sanger, Gredler and Cohn 2015]

Top image of tuatara by A. Sparrow via Flickr [CC BY 2.0; other images from Sanger, Gredler and Cohn 2015]