Edward Snowden may know a thing or two about encryption, but his remarks on encrypted alien signals aren’t sitting quite right with SETI. According to those in the business of searching for extraterrestrials, Snowden should probably keep his security advice limited to human affairs.

As we reported earlier this week, Snowden sat down recently to chat with Neil deGrasse Tyson. The conversation started out covering familiar subjects like privacy and government, but then it strayed into something a bit outside Snowden’s wheelhouse: aliens.

Perhaps seeking to impress the astrophysicist, Snowden explained how data encryption might actually be making it harder for us to chat with our cosmic neighbours, because properly encrypted signals often cannot be distinguished from random noise. Here are his off-the-cuff remarks on the matter:

“So if you have an an alien civilisation trying to listen for other civilizations or our civilisation trying to listen for aliens, there’s only one small period in the development of their society when all their communication will be sent via the most primitive and most unprotected means.”

That’s true but there’s a rub: SETI isn’t just looking for alien messages. They’re searching the sky for all kinds of signals — including waste heat signatures from extraterrestrial technologies, alien pollution, and the normal chatter of telecommunications that accompanies an advanced society. A direct communication beacon would be fantastic, but we’re not putting all of our eggs in that basket.

SETI director Seth Shostack shared these thoughts on the matter with Scientific American:

Data encryption is beside the point, Shostak said. So far, most of the hunt for alien signals has used radio waves, based on the theory that radio is a relatively easy and cheap way to send signals a long way through space.

The SETI Institute uses powerful radio telescopes on Earth to search for narrow-band signals, or signals focused at one spot on the radio dial, Shostak said. Lots of natural bodies make radio noise, he said, but the only thing that makes a narrow-band signal, as far as scientists know, is a transmitter.

Thus, a focused band of signal is a waving flag, signalling, “Hey, there’s somebody out there who can build a radio transmitter,” Shostak said. The message itself might be indistinguishable from noise if it were well encrypted, but it would still, obviously, be a message.

However, Snowden might have been onto something with his remark that there’s only a short window, time wise, in which we can detect an alien civilisation. That’s because advanced societies could very well abandon “noisy” technologies entirely. As Berkeley SETI director Andrew Siemion pointed out to me in a conversation about aliens earlier this month, “From a scientific standpoint, we have to ask the question: If they’re hundreds of millions of years more advanced, would they even still use radio technology, or electromagnetic radiation?”

Then again, there might be another way to detect the traces of hyperadvanced civilizations — hunting for signs of their destruction. As io9’s George Dvorsky explained recently, some astrobiologists have proposed we hunt for signs of advanced civilizations that have destroyed themselves in a nuclear, biological, or technological apocalypse.

Searching for signs of life beyond Earth is one of the most challenging tasks facing scientists today, and we’re tackling it from all angles. Hopefully, we’re not going to let a little encryption prevent first contact. And hey, if it turns out aliens have gone to great lengths to encrypt all of their communications, perhaps we don’t want to be talking to them.

Follow the author @themadstone

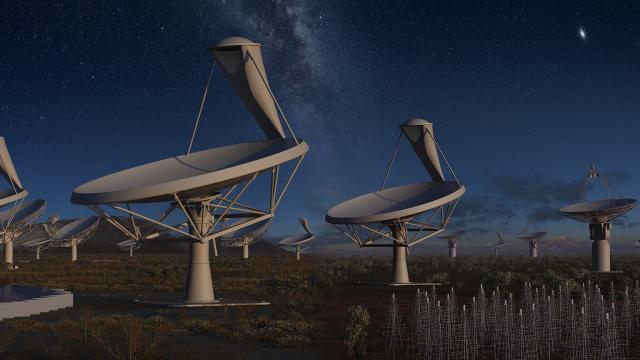

Top image: Artist’s concept of the Square Kilometer Array, via Wikimedia