While the brass in Washington continue to bicker over the consequences of allowing vaginas into open combat roles, two women have quietly completed the second, creatively-titled “Mountain Phase” of Army Ranger School. A third female soldier will have the opportunity to start the course again, a process known as “recycling”.

All three women are West Point graduates, the small remainder of a group of 19 female soldiers who pre-qualified for the one time-opportunity to attend by passing an intensive 17-day preparatory course. Their participation is only a small part of the Pentagon’s plan to finally join the rest of us in the 21st century, as it begrudgingly implements a 2013 directive to integrate women into every military job by January 1, 2016.

But what does it really take to complete Ranger School, a training program where, in the final phase alone, 22 students died before an “invisible safety net” was instituted following the deaths of four students from hypothermia in 1995?

Rangers have a long and secretive history. The Ranger name predates the Revolutionary War; a set of 19 standing orders still used by the current iteration are attributed to a Major Robert Rogers from the French and Indian War. As for Ranger School, it only has a 42 per cent graduation rate. The average student is 23 and upon successful completion of the course has lost 9kg. A select few of its graduates go on to join the storied 75th Ranger Regiment, a Special Operations unit that has conducted continuous overseas operations since September 11th and joined the ranks of elite forces such as Delta Force and SEAL Team Six.

As a group, Rangers are some of the most physically fit and tactically experienced men in the military — every one is a slightly more realistic Jason Bourne. Even the Ranger Creed is less of a creed than a set of impossible expectations: “I accept the fact that as a Ranger, my country expects me to move further, faster, and fight harder than any other soldier.” (Sounds like the brainwashing portion of the course was a success.)

The school, which is not actually affiliated with the regiment, is run by the US Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). The first Ranger School class graduated in 1950 from Fort Benning, located in Georgia. The 61-day course has three phases — Benning Phase (also known as Crawl Phase or Darby Phase), Mountain Phase (also known as the Walk Phase) and Swamp Phase (also known as Run Phase or Florida Phase).

As should be evidenced by this prime example of very silly military wordplay, each phase builds upon the previous, all designed to push recruits beyond complete mental, physical and emotional exhaustion. All of the training materials TRADOC provides for potential attendees feature the words “grit” and “adversity” in bold on numerous pages (also lots of typos). At one point there was also a short Desert Phase that came after the Swamp Phase, but it was eliminated in the mid 1990s — an interesting choice given the war zones that dominated the previous and following decades.

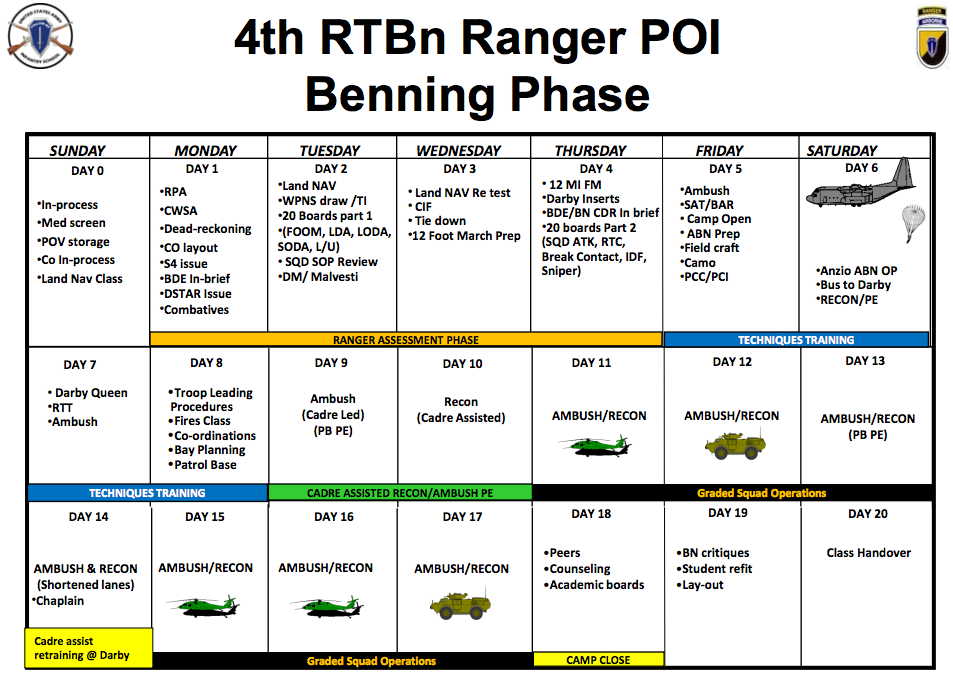

Benning Phase

Benning Phase takes place at the eponymous birthplace of the Rangers in Georgia. The gruelling first four days are known as Ranger Assessment Phase or RAP week, and a full 60 per cent of failures occur during this period. This year, out of the eligible 19 women, eight made it through this section, but all were recycled at a later point in the phase, included the two women who have now completed the Mountain Phase, who were actually recycled twice.

Here are a few things you can look forward to during the first 96 hours of your stay at Camp Darby or Camp Rogers:

- the Ranger Physical Assessment — 49 push-ups, 59 sit-ups, 8km run in 40 minutes or better, and six chin-ups from a dead hang.

- the Combat Water Survival Assessment — a 12m walk across a very high log, a 23m suspension traverse, and a jump into Lake Victory in an Army Combat Uniform, followed by a 15-minute swim in boots. Here’s a video where the recruits are doing it in 32 degree weather:

- waking up at 3.30am for a night and day land navigation test.

- a 3.4km two-man buddy run in “Army combat uniform, un-bloused combat boots, Camelback, carrying an M4, wearing a headlamp, and no headgear.”

- the Malvesti Obstacle Course, where the infamous “worm pit”, a 25m mud pit covered in barbed wire, must be traversed on both the back and belly.

- a 20km ruck march, where students carry an average of 16kg without access to water, which must be completed within three hours.

And that’s just the first four days. After that, meals are cut to one per day. The following two weeks focus on mission planning, patrolling, reconnaissance, ambushes, demolitions training, hand-to-hand combat training, jumping out of aeroplanes, sniper training, lighting fires with no hands or eyes or bodies or minds or anything, and camouflage. Then there is the Darby Queen Obstacle Course, which is comprised of 20 obstacles over 1.6km of lousy terrain.

At any time, a recruit may be told they are in charge of 10 other equally exhausted, dehydrated, hungry recruits, and they are judged harshly on their leadership skills, a theme that strengthens and continues throughout the rest of the phases. This is a school for leaders, and the Army takes that to an incredible extreme.

According to anonymous Washington Post sources, this is where the first crop of women felt they were most unfairly judged. Recruits leading patrols are graded by both Ranger Instructors (RI) and by a peer review system, and given a GO or a NO GO review. Two NO GO reviews means recycling or dismissal. On patrols, many of the women were graded well by their peers, but were later informed they had failed at least two patrols. In addition, men who were placed on patrols with women also did significantly and statistically worse.

One source said, “There’s the sense that no RI really wants to be the first one to pass a woman.” If you’re recycled, you’re required to start the last phase all over again, and graduate at a later date, but not everyone is recycled — some people just get sent home. The Army Times claims that 37 per cent of recruits recycle at least one phase. Here’s a day by day breakdown from TRADOC:

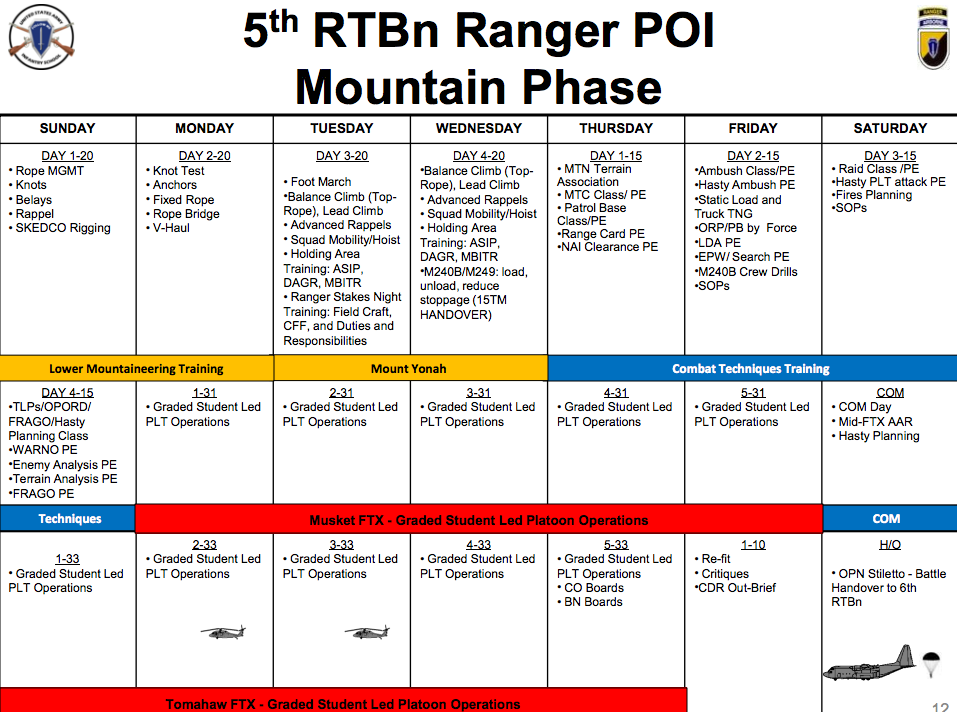

Mountain Phase

This phase moves from the confines of Fort Benning to the mountains of the Chattahoochee National Forest in northern Georgia. The focus is on “military mountaineering tasks, mobility training, as well as techniques for employing a platoon for continuous combat patrol operations in a mountainous environment.” That translates to a series of multi-day exercises that make use of the exposed, difficult terrain to encourage platoon strength and teamwork as well as promote leadership.

Again, leadership is stressed as one of the most important graded aspects of this phase. For women who have little patrol or leadership experience, this comes as a one of the most difficult aspects of the school. It’s a bit of a vicious cycle in that these women are progressing past a point never before attained by female recruits, and then failing because of that lack of experience by female predecessors.

Skills such as learning knots, repelling, climbing, anchoring and belaying are the main focus, and exercises where everything — gear, supplies, the students themselves — must be moved only by rope are commonplace. The most brutal section seems to be the final test where recruits are sent on a nine-day field exercise.

One story from Robert L. Pickett, Lieutenant Colonel US Army (Ret), as told to Mona D. Sizer in her book, The Glory Guys, claims that at one point during the final exercise students were ordered to do a 60m night rappel, only to find themselves geared with 45m ropes. So they had to “stop about two-thirds of the way down the cliff and transfer to a second rope, unassisted, in the dark.” According to Pickett, many of these exercises were done on less than four hours of sleep per day, and the one meal rule was again enforced. Here’s a shot of the Mountain Phase Calendar from TRADOC:

See that parachute at the end of the calendar? That’s because at the end of Mountain Phase, recruits often are transported via plane to Camp Rudder, an outpost of Eglin Air Force Base in Florida where the next phase begins.

Swamp Phase

Swamp Phase makes everyone remember the Indiana Jones line about snakes — it sounds like a literal living hell, and that’s saying something considering how torturous the rest of the phases already sound. In the backwater areas of the Florida panhandle, the final phase consists of days completely immersed in water, traversing swamps with snakes (maybe read a little bit about the python problem in Florida, or maybe don’t), alligators and a host of other things one would only hope to see behind glass. According to the Army website, the “18-day final phase focuses on training students for missions in coastal and swamp environments while overcoming the challenges of severe weather, terrain, limited sleep, food deprivation, and mental and physical fatigue.”

After 40-odd days of extremely rigorous activity, little food, water or sleep, it makes more sense why the 22 tragic student deaths occurred during this phase. In addition to navigating their way around the hellscape that is Florida swampland by Zodiac, swimming or hiking, students engage in mock battles with enemy combatants, or find themselves with little time to rescue “hostages.” Drops from cargo planes or attack from enemy air fire is part of the drill and made easier by the fact that the school takes place near an Air Force base. And that utilisation of air support adds a measure of real life combat awareness that allows Ranger School (or any of the elite training schools) to forge hardened soldiers for the government’s most dangerous, difficult, and often dirty work.

Should any of the women complete the final Florida Phase of the school, they will not be invited to join the 75th Ranger Regiment — that’s still off limits to women. But that could change next year, if the Army decides this little adventure has proven that women have the mental fortitude and physical endurance for combat. It’s a milestone that comes 17 years after Demi Moore took a set of clippers to her head and picked up a Razzie for her role in G.I. Jane as the first woman to attempt Navy SEALs training, a program that has still not been opened to women. It should be noted, the movie did get one thing right — the women who participated in Ranger School did shave their heads in solidarity with their fellow recruits.

According to a recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, it may take up to two years for women to actually be placed in combat positions, following training, testing and assignments. That report alone explains why there have only been three four-star female generals (or the affiliated armed force equivalent) in the military, and why the only medal of honour ever awarded to a woman was issued after she was taken hostage during the Civil War.

There are so few roads to top level command offered to women, which also means the recognitions of their achievements remain disproportionately low. But two women may soon be sporting a set of coveted gold and black tabs, an accomplishment worthy of very high praise, regardless of gender.

All images and screenshots courtesy of the US Department of Defense. Video courtesy of ABC News and the US Army.