People don’t die of the Black Plague in the 21st century — except when they do. And the disease won’t be going away any time soon.

Earlier this month, a high school student in Colorado died of the disease. On average, seven people in the US catch the plague every year; some years, it’s only one, and in other years, it’s as many as 17. Worldwide, the plague strikes about 2000 people every year, and about 10 per cent of them will die. That’s quite a step down for the disease that killed nearly a third of the population of Medieval Europe in its heyday. But why hasn’t the plague faded quietly into the history books?

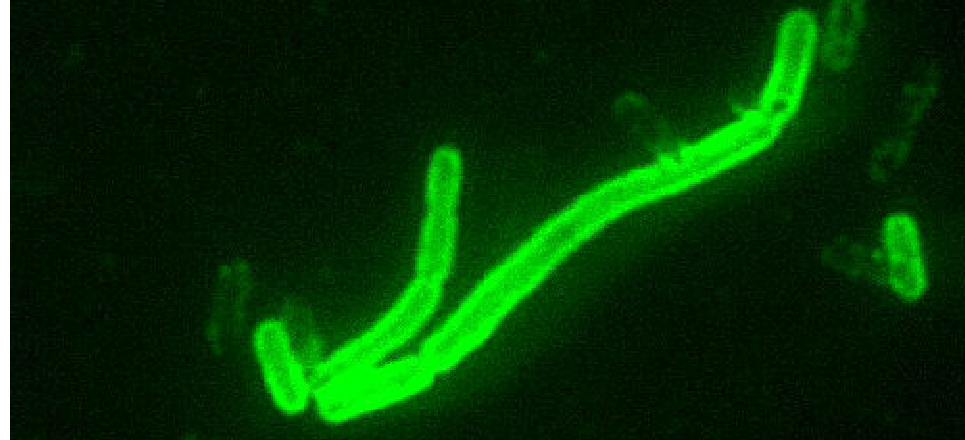

Meet Yersinia pestis

The bacterium Y. pestis. Image credit: CDC via MicrobeWiki.

An Italian cobbler and tax collector named Agnolo di Tura lost his wife and five children to the Black Death when it struck Siena, Italy in the 14th century. He wrote:

The victims died almost immediately. They would swell beneath the armpits and in the groin, and fall over while talking. Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another; for this illness seemed to strike through breath and sight. And so they died … Members of a household brought their dead to a ditch as best they could, without priest, without divine offices. In many places in Siena great pits were dug and piled deep with the multitude of dead. And they died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in those ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. … And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.

That horror is the handiwork of a bacteria called Y. pestis, which spends part of its life cycle in the digestive systems of fleas. There, it multiples until the flea’s esophagus is clogged with bacteria, so when the flea bites and tries to feed, it chokes on the teeming mass of bacteria in its throat. The flea vomits the pathogen into the bloodstream of its unsuspecting host, passing the infection on.

Y. pestis normally infects the lymphatic system, which is part of the immune system. Lymph nodes in the groin, armpits, and on the neck swell up, oozing with blood and pus. These swellings, called buboes, give the disease its proper name: Bubonic Plague.

But the bacteria can also infect the bloodstream, causing what’s known as septicemic plague. This is what happened to the student who died in Colorado on June 8. Septicemic plague moves quickly, and often patients are in very bad shape before they even realise they’re infected. It brings diarrhoea and vomiting along with the fever, and patients sometimes develop gangrene in their fingers, toes, and noses. This blackened, dead tissue gives the disease it’s other name: the Black Plague.

If it’s not treated in time, the bacteria that cause the plague can migrate into the lungs. Patients begin to cough, releasing aerosolised droplets of plague into the air. Anyone who breathes it in will soon have the Black Plague growing in their lungs, too. The plague spreads very quickly this way, and some historians think this is how an epidemic wiped out half of London in the 17th century.

Oh, Rats!

Image credit: Ivan Tunja via Wikimedia Commons

Normally, the fleas that carry the plague live on wild rodents like rats, marmots, squirrels, and prairie dogs. Infectious diseases and their hosts eventually adapt to one another, to a certain extent, so plague-carrying rodents can die of the disease — but generally it moves among them without killing very many, very often. Indeed, one of the ways scientists can tell which animals are a disease’s natural hosts is by tracking down the infected species that don’t suffer epidemics. Of course, occasionally a major outbreak will flare up among the wild rodents in an area, leading to a higher death toll than usual.

Only rarely do the fleas, or the bacteria they carry, make the leap to humans. Scientists who study epidemics say that rodent populations are a “reservoir” for the plague.

That said, the plague can make a jump to humans any time they come into contact with infested fleas, which is usually when people get too close to wild rodents or their nests. Pets and livestock can also pick up the fleas, the disease, or both from wild rodents and then pass the infection on to people.

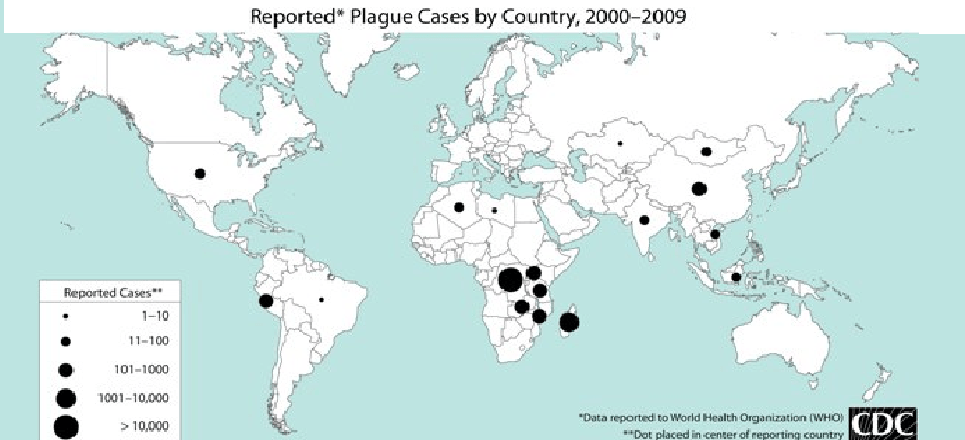

It’s actually surprising that plague outbreaks aren’t more common. Historians think the disease probably originated in central Asia, but today Black Plague is endemic among wild rodents in the western part of North America, in central, eastern, and southern Africa, in South America, and in much of Asia. It mostly sticks to rural areas — small towns and farming villages — but outbreaks still occasionally happen in Asian and African cities. In the U.S., most of the people infected are camping, hiking, or hunting in areas where infected rodents live.

And that’s why it’s still around. The plague survives because it has a natural reservoir of wild rodents, which it’s neither feasible nor wise for us to eradicate. It’s followed us through history, and it probably always will.

The Modern Day Plague

Image credit: CDC

Fortunately, the plague isn’t the apocalyptic specter that it was in Medieval Europe. Modern doctors can treat it pretty effectively with antibiotics most of the time. That’s why it’s less terrifying than diseases like Ebola, a virus for which we have no vaccine and no effective treatment (although researchers seem to be getting close). In fact, there actually is a vaccine for the Black Plague, but it’s usually only given to people whose jobs put them in regular contact with infected rodents, according to the World Health Organisation.

Mortality rates among the few people who do catch the plague are about 8-10% worldwide, but that average isn’t really a good reflection of reality. In the U.S., people rarely die from plague; the recent case in Colorado made the news precisely because of its rarity. In some areas, where health care is less accessible, that death rate is higher. In very remote areas, it’s hard to tell what the death rate from plague really is, because cases may go unreported, any many are never diagnosed at all.

The plague may be survivable these days, but it’s still a harrowing experience. Lucinda Marker and her husband, who live in New Mexico, shared their account of the plague with the Guardian in 2010:

I remember in the hotel, getting sicker and sicker, having this feeling of impending doom and darkness. That was a characteristic of the plague back then. The burning fever, the achiness; it was so accurate. No one knows why it affected John more than me. During the Black Death, there were people who survived and there are theories that some of us over here have genes from our European ancestors that protect us.

John lost his legs to the disease; Lucinda was relatively unscathed. The only difference between what they experienced, and what their ancestors went through 700 years ago, was that they had a chance to survive. And ultimately, that’s what matters.

Picture: Rita Greer via Wikimedia Commons