For an incredibly simple concept — keeping you dry — rain jackets have involved into awfully complicated products. Air flow rates, water pressure resistance, durable water repellent coatings, hard shells, soft shells… the list of technical terms goes on. Here’s what they all mean, and how you can use them to find the best jacket for you.

Hard Shell vs. Soft Shell

Outdoor Research, which manufactures both styles, says:

“There is no formal industry-wide definition for the terms “soft shell” and “hard shell.” The “soft shell” came into vogue about a decade ago when some fabric manufacturers began making soft, stretchy materials that repelled wind and light precipitation, but weren’t fully waterproof. In cold, dry climates, these “soft shells” worked 70 per cent of the time or more for an outer layer. The first soft shells were called that name so that they could be differentiated from the hard, less-breathable but more weather-protective shells that were standard technical outerwear.”

With recent advances in materials technology, the line between the two is becoming increasingly blurred. But, you can generally take “hard shell” to refer to a jacket made with a waterproof/breathable membrane and “soft shell” to mean one that goes without. Yes, that does technically mean a soft shell won’t be fully waterproof, but it makes up for that with much greater breathability.

You see, there’s two things trying to get you wet outdoors: rain and sweat. An old rubberised rain slicker of the kind worn by fishermen is 100 per cent waterproof. But, immediately after putting one on and doing anything remotely active — like walking — you’ll become clammy with sweat and, soon after, utterly soaked through with it. That material is also a 100 per cent barrier to sweat and water vapour trying to escape your body.

So, you need your rainwear to not only keep water out, but to let it escape your body too. In light rain or misty conditions, this may be best handled by a soft shell, most of which are capable of keeping out light precipitation and which maximise breathability. The same goes for strenuous physical activity, where the limited breathability of a hard shell may make them impossible to wear, or in below-freezing conditions, where you don’t have to worry too much about water ingress anyways, because it’s frozen.

But, faced with steady rainfall or anything heavy and you’ll need that hard shell. The big arms race in outdoors apparel over the last few decades has been in maximising breathability while retaining waterproofness. Manufacturers also compete to reduce weight, enhance durability and, in recent years, have even introduced stretchiness to the fabrics, all while retaining the ability to keep water out.

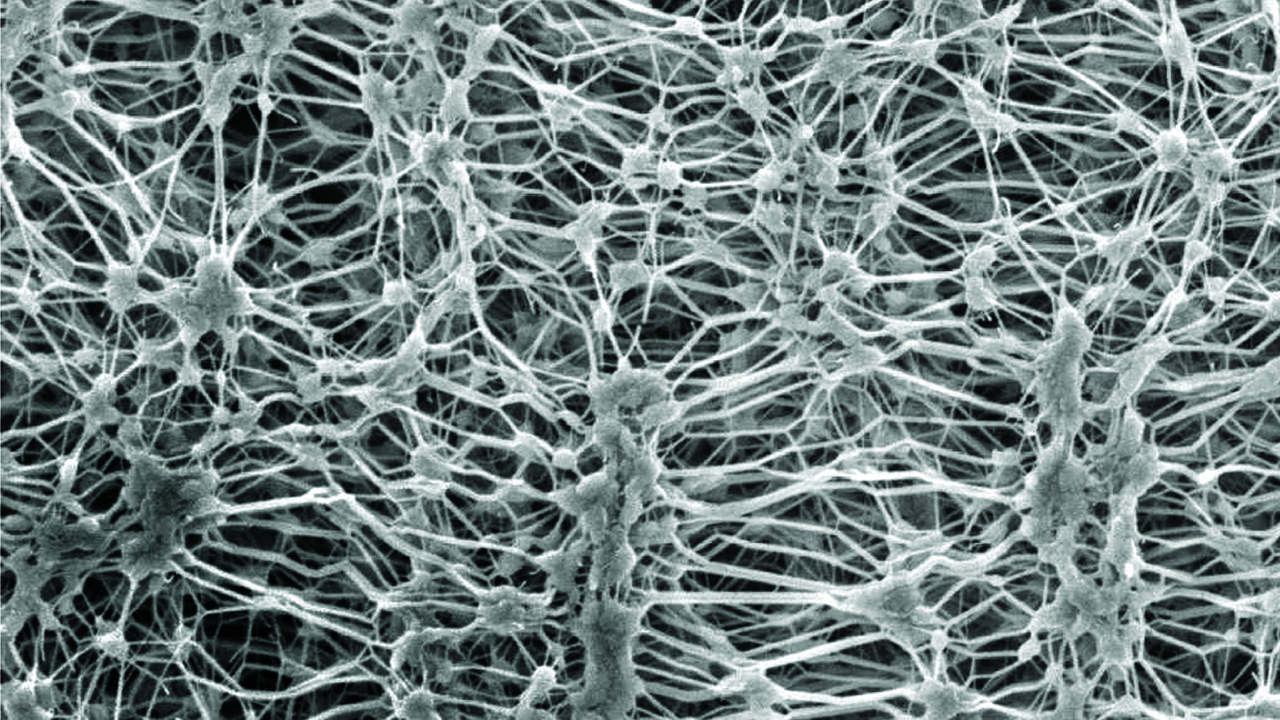

The Gore-Tex membrane, under a microscope.

Gore-Tex, Kleenex And Jeep

Way back in 1969, a man named Robert W. Gore was experimenting with polytetrafluoroethylene, better known as Teflon. By heating rods of that material and quickly yanking them apart, he was able to form a microporous material that was about 70 per cent air.

Those pores are small enough to keep out drops of water, but large enough to allow water vapour — sweat — to pass through.

His family’s company, Gore-Tex was formed to produce the material, which rose to fame as the first waterproof/breathable membrane incorporated into rain jackets from virtually every outdoors brand. In the decades since, Gore-Tex has continued to innovate both with new types of waterproof/breathable membranes and other technical products. One of their largest product ranges is in medical implants, where expanded polytetrafluoroethylene is used to construct heart patches, synthetic ligaments and other life-saving stuff.

Much like the word “Jeep” is casually used to define any 4X4 or “Kleenex” has come to mean any tissue, “Gore-Tex” is used by the general public to refer to any waterproof/breathable fabric. It shouldn’t be, not only does that company now produce a wide range of membranes with differing technical merits, as well as many other products, but it also fails to appreciate the full range of waterproof/breathable membranes that are now available, the best of which often come from other brands.

Layers, And What They Do

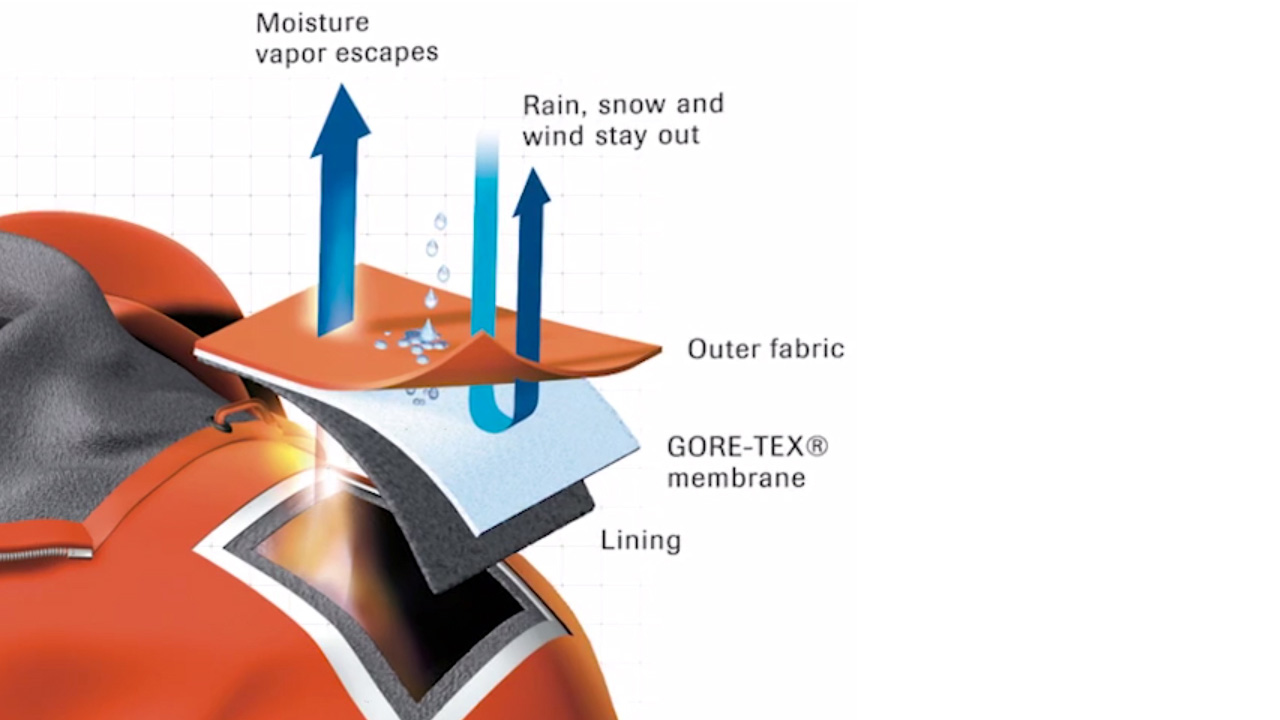

You can’t just run around the woods in a sheet of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene. It’s a very thin, very weak material that would almost instantly suffer tears, cuts and abrasion. To make rainwear from it, manufacturers have to sandwich it between two layers of protective material. This “three-layer” construction has become a more technical way for those in the know to say “hard shell”.

All three are bonded together to create a uniform fabric that feels and moves and (hopefully) stretches like a single piece. Just one that’s now waterproof, breathable, comfortable to wear and capable of withstanding abuse. Any seams in clothes made from this material should be taped — untaped stitches let water in.

On the inside, next to your skin, is typically a soft, brushed liner that facilitates comfort, breathability and which protected that delicate membrane. Newer jackets may even employ a synthetic wicking material for this layer to maximise the surface area of the jacket that evacuates your sweat. Next is the membrane itself, then the outer layer, which is there to protect it from the outside world while retaining good breathability so hot, moist air from your body can continue outwards.

You’ll see some jackets described as two-layer or 2.5-layer; confusingly, they all actually use three layers of construction. Two-layer will be the most affordable. With it, the inner liner is a stitched-in, free-hanging mesh rather than something bonded to the membrane. Conversely, 2.5-layer jackets are lighter, replacing that inner liner with a protective coating rather than a bonded fabric. 2.5s make great “emergency” rainwear, when you may need something light to stuff into your pack for unexpected storms, would like it to stand up to that for a few years of use, but don’t need the day-in, day-out durability of a three-layer.

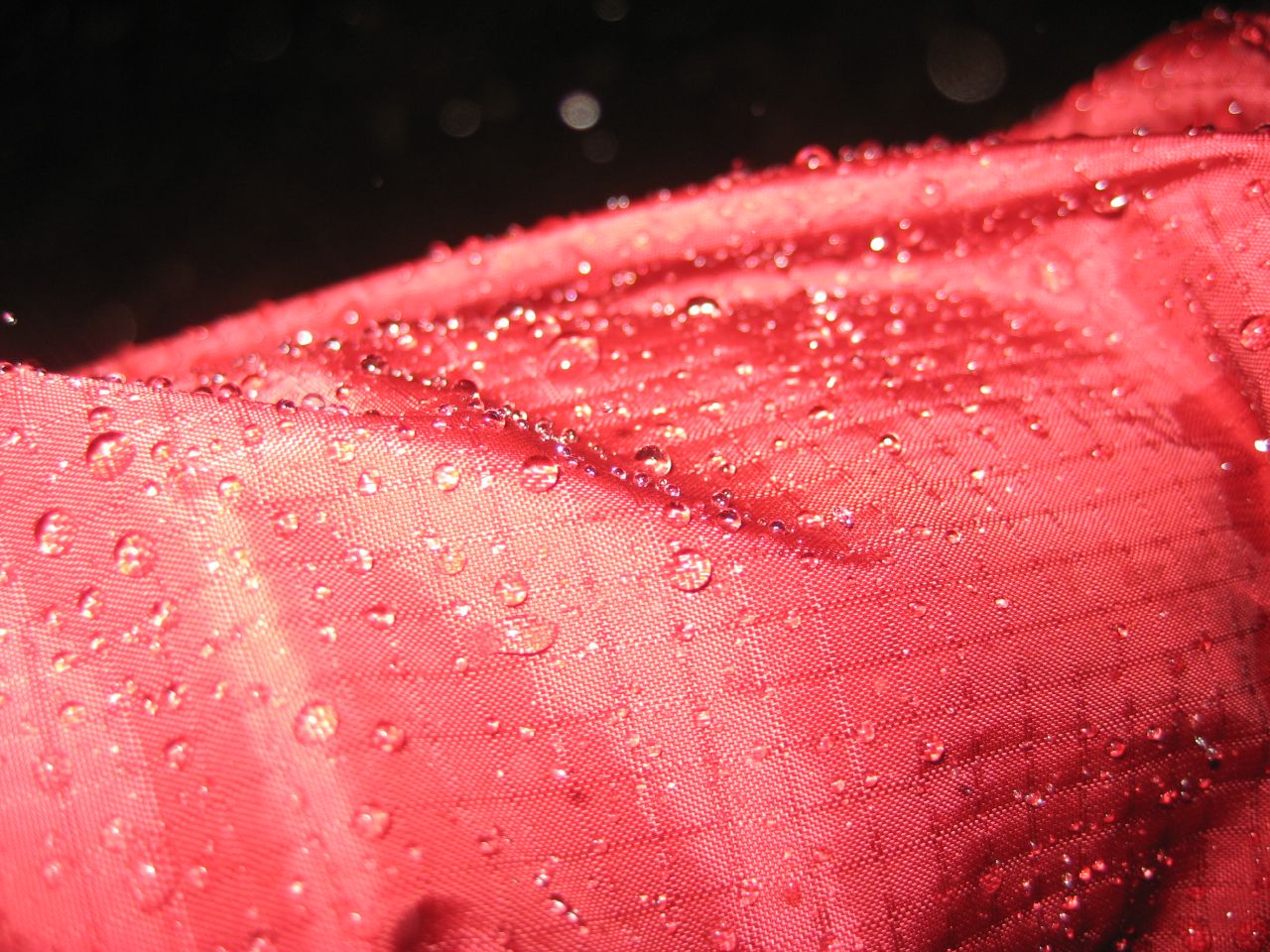

“Durable” Water Repellant Coatings

Three-layer’s tough, synthetic face has always done a great job in giving rainwear strength and durability, but it also creates something of an achilles heel. Brand new, the outer face is treated with a Durable Water-Repellant coating; when you see water bead up on the surface of a jacket, that’s the DWR at work. But, this wears off with time and use and, when it does, that outer layer may then become soaked-through with rain. While this outside water won’t reach you through the membrane, it does massively reduce the material’s breathability, leaving you soaked in your own sweat and defeating the whole purpose of waterproof/breathable rainwear in the first place.

On some jackets, this DWR can be revived by washing and tumble drying (on low!) or reapplied with a spray-in or wash-in treatment. Wet-out is a gradual process that will effect your rainwear over time, not something that will instantaneously sneak up on you. Monitor the performance of your gear as you use it and care for the DWR as appropriate.

Many soft shells also employ DWR coatings to give them an extra element of weatherproofness. With any fabric, follow the care guidelines provided by the manufacturer or retailer.

Columbia just announced a new waterproof/breathable fabric that does away with the problematic outer layer and its need for DWR, instead using a tough-rubber-like membrane perforated with millions of microscopic holes to make it breathable while keeping out water. OutDry Extreme uses a wicking inner liner to maximise dryness and comfort. More soon.

Under The Hood

When you shop for a new car or motorcycle and you care about performance, there’s three numbers that matter: weight, horsepower and torque. By comparing them across brands and models, you can arrive at the fastest or most capable vehicle within your budget.

Is there a similar method for cross-shopping rainwear? Well, yes and no. The two most important numbers you can research are water resistance and breathability.

Water resistance is expressed in millimetres and is the water pressure a fabric can take before water penetrates it. The higher the number, the higher the pressure it can withstand. For instance, my favourite WP/B fabric, Polartec Neoshell, can withstand 10,000mm of water pressure before water will pass through. That’s the bare minimum to be considered “waterproof”, but is still equivalent to being sprayed with a firehose from 10m or so. Basic Gore-Tex is rated at 28,000mm.

Breathability is the rate at which water vapour can pass through the fabric. This is where comparing different materials can be difficult, as there is no standardised test or even agreed on number for representing results across the outdoors industry. So, my Neoshell jacket flows vapour at .5 cubic feet/minute, which is claimed to be four to five times the rate of plain-jane Gore-Tex. But, Gore lists its numbers in g/m2/24 hours. How on earth can I compare CFM to grams-per-square-metre-per-24 hours?!

Adding insult to injury, the lack of a standardised testing procedure means you can’t take a manufacturer’s claim at face value; methodologies vary. Look for same-method testing in independent product reviews or use a manufacturer’s numbers to compare products within a brand.

We’re currently testing the new NWAlpine Eyebright jacket. Instead of traditional three-layer construction, it uses a non-woven Dyneema core woven through with inner and outer layers of an eVent membrane. The Dyneema is inherently waterproof, while the membrane inserts breathability. It’s radically light and packs very small.

Are Alternative Materials For You?

Of course, not every rain jacket out there is a three-layer laminate with a WP/B membrane. There’s vinyl ponchos, waxed-cotton Barbour motorcycle jackets, wool gabardine and even tightly-woven cotton.

If you’re shopping for round-town, casual wear, you may be able to get away with one of these. And hey, if they don’t work, you’ll only be out a few hundred bucks. In the outdoors, getting wet can kill you, use a modern technical fabric.

The right cut and features will allow you to move freely, even while climbing. Photo: Thomas Senf.

Features

Beyond just the material the jacket is made from, its feature set is what makes it comfortable, versatile and appropriate for your unique needs. Climbers, for instance, need a hood designed to fit over a helmet while any of us can benefit from a jacket designed to breath better through zip-open vents. But, features do add weight, price and potential failure-points to a jacket. So learn what they do and try to closely match a jacket’s spec to your needs.

Fit: You want a jacket that suits your body type. Be honest here, not only will a beer belly swell a trimly-cut jacket, but you’ll look best in an item of clothing that fits you correctly all-around. You should be able to buy a jacket in the appropriate size for your shoulders, then layer underneath it without sizing up; that space is already built in.

Articulation: Jackets cut for climbing and similar activities will have underarm gussets and a general construction that allows you to lift your arms over your head without lifting the jacket off your lower torso. I prefer this feature for general active use as it allows excellent freedom of movement without sacrificing coverage during any activity.

Pit Zips: Zip-open vents underneath your armpits massively ramp-up breathability when open and should still keep most rainfall out due to the protected nature of their location. Consider them essential if you plan to be active while wearing the jacket.

Collars: I prefer a collar that goes over my chin and wraps all the way around my neck, independent of the hood. Comfort linings on the back of the neck and chin — areas that rub — are a welcome touch. Tall collars like these really keep the weather out when zipped all the way up and prevent rain from falling down your neck while you have the hood down.

Hoods: You’ll want one in heavy rainfall, but you’ll also want one that stays out of the way any other time. Look for drawcords around the opening, a re-enforced cap-style brim and maybe a design which allows you to hide the hood in the jacket’s collar. If you plan to wear a helmet, you’ll need an up-sized hood designed to be compatible with one, plus a separate drawstring adjuster to draw it tight to that helmet.

Cuff Adjusters: Velcro or similar “straps” on the cuffs allow them to be sized large enough to tuck gloves in or cinch down over your bare wrists. Some lightweight jackets use elastic cuffs or even stretchy neoprene. It’s just a matter of personal preference which will work best for you.

Torso Adjusters: Drawstrings under your pecs and at the jacket’s hem allow you to tailor its fit to suit your body and the layers you’re wearing. Nice to have, but no replacement for a properly-cut jacket that suits your body type.

Zippers: Any zipper on a rain jacket should be water resistant, at a minimum. Fancy PU-coated zippers work very well, but still benefit from being covered by a storm flap. On expensive jackets, look for “zipper garages” that prevent them from being snagged and from touching your chin.

Pockets: The only good pockets on a rain jacket are waterproof pockets. This can be easily achieved by sticking them inside or more expensively executed by giving outside pockets waterproof zippers. Consider the relative location of pockets and any harnesses or packs you may wear. These may limit access, obscure volume or even prevent the use of pockets altogether.

Packed Size And Weight: Important if you’re stowing a jacket in a backpack or similar. More money typically nets you less size and weight.

Damn, This Is Complicated!

Sorry, we warned you. The more you learn about technical outerwear the more you wish you didn’t know. And yes, once you learn just what a jacket can be capable of, that’s when you start buying silly-expensive ones, like my $US500 Westcomb Apoc.

What that jacket nets me is unprecedented breathability paired with complete waterproofness, quality construction, a maxed-out feature set, strong colour choices and a fit that flatters my athletic body. That stuff is all important to me because I’m a) vain and b) spend an awful lot of time in the outdoors, often in front of a camera.

You can make this all much simpler and cheaper by simply visiting the outfitter of your choice and asking the questions raised in this article. How waterproof is it? How breathable is it? How do those numbers compare to jackets up or down the price scale? How durable is the DWR and how easy is it to revive? Does it fit me? Can I use the pockets? Is it light enough for my needs? Find those answers within your budget, complete with a reputable brand name, and you’ll be able to stay dry no matter how bad the weather.

Picture: Chris Brinlee Jr