Sometime in the next two months, the FDA will vote on whether to approve flibanserin, a new drug to treat women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder, or lack of desire for sex. The drug has been touted as “female Viagra,” in the sense that it helps bring sex back into these women’s lives. But Flibanserin doesn’t actually work like Viagra. Here’s how it works.

Viagra, and drugs like it, act on the erectile tissue inside the penis, to increase blood flow in men with circulatory system problems. Men who use erectile dysfunction drugs don’t have a problem desiring sex; their bodies just don’t respond to that desire.

Women with HSDD — about 8-9% of women between the ages of 30 and 60 — have a very different problem. There’s nothing physically wrong with their genitalia: they can become aroused and have intercourse, even orgasm, but they feel no motivation to have sex. For some reason scientists still don’t understand, the “desire circuits” inside their brain aren’t turning on, either for their partners or even for their own fantasies. Flibanserin, currently under development by Sprout Pharmaceuticals, acts on the brain, and claims to help some women turn those circuits back on. Here’s how it works.

The Neuroscience of Desire

Women with HSDD seem to experience erotic situations differently than women with normal sexual function.

Some researchers think this happens because they can’t easily dial down the activity of certain parts of the brain. One 2009 study of women with HSDD found that the parts of their brains that were responsible for monitoring internal emotional states were overactive when they watched erotic videos — as if their brains were focused on judging whether their reactions were appropriate, instead of living in the erotic moment. Flibanserin helps to change the balance of active circuits in the brain by acting on the neurons that are normally controlled by two neurotransmitters: serotonin and dopamine.

Neurotransmitters are the chemicals that neurons use to send signals to other neurons. They’re released after an electrical signal moves through a neuron: When the signal reaches the end of a neuron’s axon, it releases the chemicals into a tiny gap between neurons called the synaptic cleft. Neurotransmitters diffuse across the gap and latch onto specific receptors on the neighbouring neuron. When neurotransmitters dock into receptors, they start chains of chemical reactions that can help get an electrical signal moving through the new neuron.

Or not. Neurons aren’t simple on/off switches. Some neurotransmitters excite the neurons they dock to and push them toward firing, but others damp down electrical reactions. Every neuron is constantly receiving both types of signals from its neighbours — and the sum of the signals determines whether the neuron fires or not. The interplay between excitatory and inhibitory signals is one of the things that makes brain function so complex, because it allows the same circuits to react differently to a variety of different situations.

Neurons can even change how they react to the neurotransmitters that are released by their neighbours, by adding or removing receptors for specific chemicals to their surface. A neuron can become more sensitive to dopamine, for example, by adding more dopamine receptors to its surface.

What’s more, each neurotransmitter can bind to a family of related receptors, and each one can be tied to a different set of chemical reactions. A neurotransmitter on one type of receptor can excite or depress the cell a different amount than if it was docked at a different receptor.

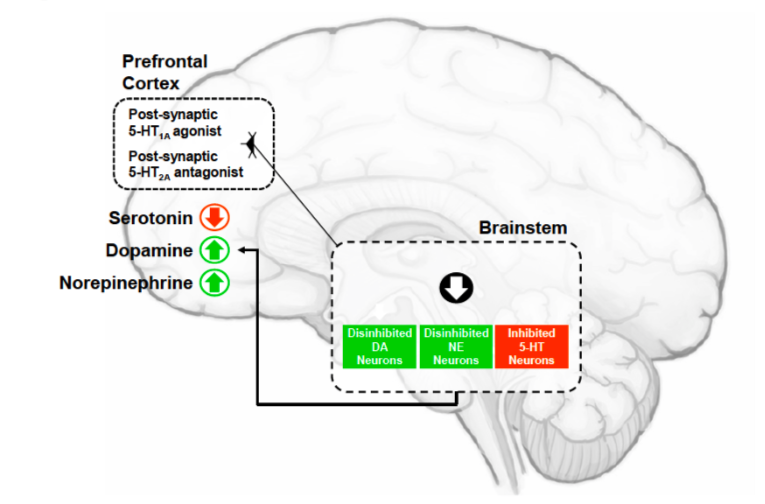

That distinction is important, because this new drug, flibanserin, can act on two different types of serotonin receptors. When it binds to a 5-HT1a receptor, it has the same affect as a serotonin molecule. But when it latches onto a 5-HT2a receptor, it blocks the normal effect of serotonin. Serotonin normally inhibits neurons, which means flibanserin tends to reduce neuron activity in areas rich in 5-HT1a receptors and increase it in neurons that have 5-HT2a receptors. Researchers assume that women with HSDD aren’t making enough serotonin in their brains in general, but flibanserin only mimics the neurotransmitter’s effect on one subset of neurons — the ones that have 5-HT1a receptors.

So Does It Really Work?

The net result? Flibanserin quiets neurons in a part of the brainstem called the dorsal raphe nucleus and the memory-and-emotion hippocampus — but it seems to have its strongest quieting effect on the cerebral cortex, where all that ‘self-judging’ activity is taking place.

And because the brain is a network, changing the activity of one set of neurons can also change the behaviour of the neurons in the rest of their circuit. The downstream effects of flibanserin aren’t entirely clear, but one study in rats showed that it can make neurons in the cortex release both noradrenaline and dopamine, neurotransmitters that typically kick motivation into gear. It’s possible that a rise in available dopamine, paired with the drug’s mild effects on one type of dopamine receptor, bumps up the activity of the brain’s reward circuits and makes the prospect of sex more exciting.

But the drug’s effects are subtle. This is not a miracle sex drug that makes women pant for more. In fact, because the drug’s main effect is to restore the brain’s ability to inhibit the parts of the brain that normally suppress ‘desire’ circuits, it won’t even work on most women — their inhibitory circuits work just fine, thank you. Flibanserin only works on HSDD sufferers who have low serotonin levels. And even for those women, Sprout Pharmaceuticals’ clinical trials have shown a complex and fairly modest effect.

And like any other drug that affects brain function, flibanserin can have side effects. According to Sprout Pharmaceuticals’ FDA briefing document, 9 to 11% of women taking the drug in the clinical trial experienced dizziness, fatigue, and nausea (as opposed to 2 to 5% of the women on a placebo). The drug can also interact with other substances that have a depressive effect on the brain, such as alcohol, and amplify their effect.

Earlier this month, the FDA’s advisory committee recommended approval of the drug, so long as it is tied to a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) that helps doctors prescribe it correctly, and keep a close eye on any side effects. The FDA will now decide whether flibanserin’s benefit for the subset of women it works on outweighs its side effects. It remains to be seen whether that group of women is large enough to recoup Sprout’s 50 million dollar investment in the drug.

[Borsini et al. 2002, Cooper er al. 2003, Jovanovic et al. 2008, Montgomery 2008, West et al. 2008, Arnow et al. 2009, Invernizzi et al. 2009, Stahl et al. 2011]

Picture: Sprout Pharmaceuticals | FDA briefing document