As rescue efforts in Nepal begin to shift to recovery mode, relief workers in the earthquake-ravaged country are focusing on infrastructure — including the catastrophic loss of so many historic structures. And they’re increasingly using emerging technology to do it.

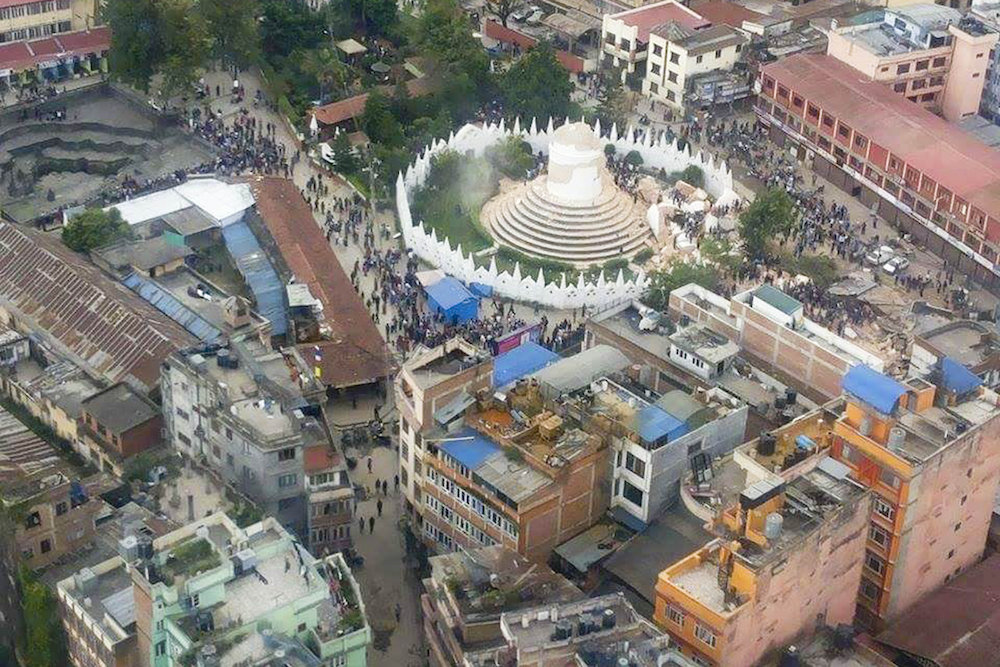

How bad is the damage? Earlier this week UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre released a report on its Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Property, seven sites that include Buddhist monuments and Hindu temples which date to the fifth century AD. Of the seven properties, three of the sites — the “Durbar squares” or urban plazas of Kathmandu, Patan and Bhaktapur — appear to be almost totally destroyed, their statues toppled, their towers snapped in half.

A Cost-Effective Assessment

The teams of archaeologist, historians, scientists and local architects charged with repairing these sites have two jobs: they must first make a thorough and accurate survey of the damage, then formulate a plan to rebuild. But after disasters that paralyse airports and freeways, it’s often hard to get teams on the ground quickly, and even then the assessment part can take years.

The World Monuments Fund (WMF) has been working with the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) for over a decade on a project called Arches to solve this problem. The software system developed by Farallon Geographics allows groups of any size — cities, engineers, preservationists — to create open-sourced digital inventories of cultural assets that can help provide an instant before-and-after comparison in the wake of a disaster. This means detailed GIS data, satellite imagery, photographs and laser scans, historical details — all in one place for quick reference.

“It all comes back to having good information at the outset, and that’s the issue that we’re hoping to address with Arches — to give a better tool that will allow for organisations to create more effective inventories,” says the WMF’s Yiannis Avramides. “It’s a big problem in our field, because it’s chronically underfunded, like a lot of other heritage professions.”

Arches’ precursor MEGA-Jordan allows groups like the WMF to collect large amounts of data about a historic site in one place including images, digital renderings and satellite maps

Saving History In a War Zone

The need for a program like Arches originated with the work that groups like the WMF were doing in the Middle East. Many heritage sites in the region there have been threatened by ongoing political unrest, their contents plundered by troops or structures destroyed in combat. Certain sites in Jordan and Iraq that suffered complete losses of their ancient monuments prompted a precursor to Arches called the Middle Eastern Geodatabase for Antiquities (MEGA), a web-based geographic information system (GIS) to index the sites and any changes happening around them.

With the proliferation of satellite imagery, it’s easier for scientists and historians to keep relatively current visual tabs on a specific area, says Avramides. But it becomes more complicated when monitoring the ongoing condition of a heritage site, which can be hundreds of square miles. Using the tool, scientists can not only map assets but also track and document tiny changes to the landscape over time, including signs like tents or vehicle tracks which might mean someone is looting the site.

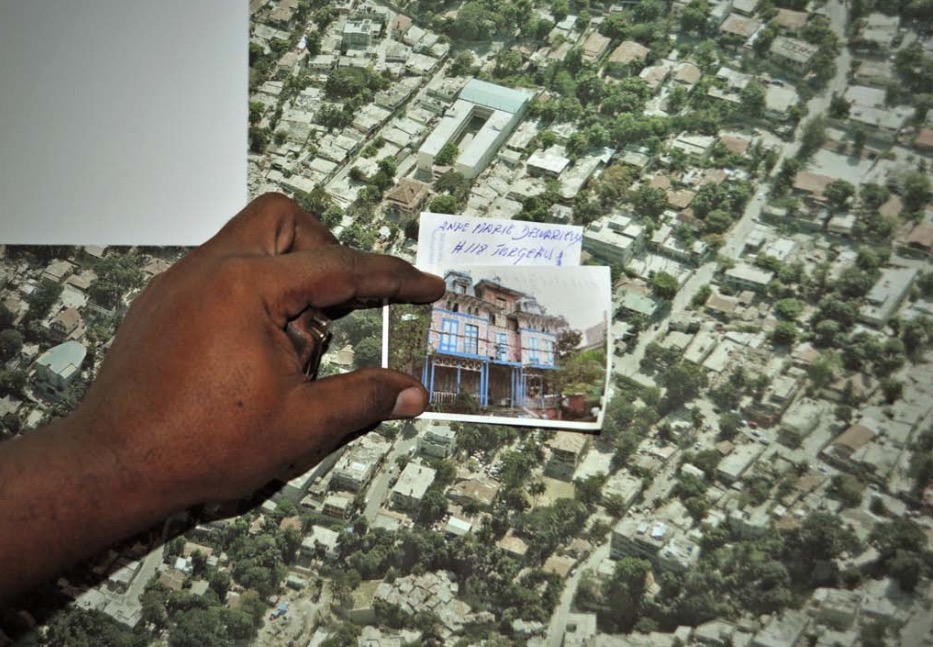

After Haiti’s earthquake, the WMF was able to survey satellite imagery remotely then followed up with on-the-ground photography to document the damage in a historic neighbourhood

A Field Test In Haiti

After a disaster, workers begin by putting together a report called a preliminary damage assessment. This quick survey is like architectural triage, which can help them decide which buildings need the most attention. What was once accomplished on paper with lots of legwork can now be achieved with a digital inventory.

After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the World Monuments Fund was particularly concerned about the damage to over 300 ornate Gingerbread-style houses in a Port-au-Prince neighbourhood. In the days after the earthquake they were able to assess the situation remotely by looking at new aerial images for signs of destruction, like debris scattered around the homes. The WMF even partnered with certain satellite companies that could provide better angles on images or capture them at a particular time of day to make sure details weren’t shadowed.

This kind of remote assessment can save organisations time and resources which might prevent further damage from looting or even potential aftershocks, in the case of an earthquake. By the time the World Monuments Fund team landed in Haiti, it didn’t need to do a house-by-house inventory — the group of historians and and engineers had a fairly good idea of which homes needed the most work, helping them put together a prioritised plan for restoration efforts.

Community-Sourcing Data

In the last few years we’ve seen a tremendous transformation in the kinds of tech tools which can help infrastructural first responders to do their jobs better. A crowdsourced version of this kind of asset mapping has already been seen in Nepal, where OpenStreetMap launched an effort to map disaster relief routes. The public could be employed to help find and tag damage to buildings, or share their photographs of a certain site before it was destroyed.

A still from drone footage captured by Shreejan Bhandari via AP shows the crumbled Dharahara Tower, which was nine storeys tall before the earthquake

The kind of rapid assessment imagery that Arches replies upon is undergoing another revolution as well due to the use of drones. Already, footage from several drones of damaged sites in Nepal has made its way online. Now recovery teams won’t even need to wait for new satellite imagery to work from — a drone operator could work on-site, recording new aerial footage while looking at pre-disaster maps for a real-time comparison. “This has become a very attractive and cost-efficient way of getting arial footage,” says Avramides “From what I have seen it seems like Nepal will be a real proving ground for UAV technology in general.”

My conversation with Avramides got me thinking about how important it is that cities take this kind of inventory as a precautionary measure against any kind of disaster — natural or man-made. So far, Los Angeles has been the first to mount a large-scale citywide survey using Arches, collecting all the data for public use at HistoricPlacesLA. Just yesterday morning we had a tiny earthquake here in LA and I immediately thought of my walk with the city’s seismologist, who told me how the large-scale destruction of so many historic buildings at once would be extremely difficult to address because all the documentation about them would need to be digitised first.

With these tech tools in place, it might not take as long to put the city back together again after the big one.

Picture: AP Photo/Niranjan Shrestha