As the drought in Southern California continues for a fourth punishing year, depleting groundwater reserves and demanding large-scale restrictions on usage, residents are regularly forced to confront the more unsustainable aspects of contemporary US life. For many, that means swapping their natural lawn for a simulated version.

Can you tell which California lawn is real and which is synthetic? Image via AP

As The New York Times and Los Angeles Times have recently noted, the demand for artificial turf — commonly referred to by the brand name AstroTurf — is on the rise in the United States and with it, controversy over its merits. While some proponents celebrate ditching natural grass as a to reduce water use, others point out that synthetic coverings reduce the viability of lawns as ecological habitats and that making is itself a resource-intensive manufacturing process in itself.

As the debate grabs headlines, it provides a good opportunity to explore the technology and engineering behind manufacturing artificial grass and the surprisingly important role it plays in how we experience the world around us — from the millions of square feet of ubiquitous lawns that stretch across the country, down to the design of the perfect blade of grass.

Mimicking Reality

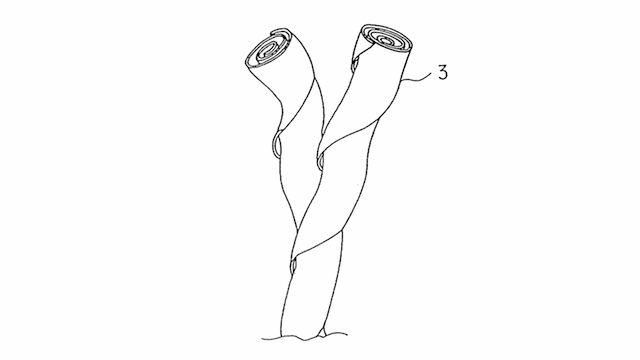

A cross section of a spiralled blade of artificial grass, among the more recent advances in aesthetic fidelity to natural grass, reveals the preoccupation with not only mimicking natural phenomena, but improving on them through engineering. US Patent No. 5,601,886, “Artificial Turf,” 1997

To learn more about the meticulous process of manufacturing nature, I perused the database of the US Patent and Trademark Office for AstroTurf product reveals over its four decades of technological development.

There’s a clear theme that emerges in these collections of drawings: the greater and greater fidelity with which artificial turf attempts to depict real grass. The inventors’ engineering efforts seem squarely focused on reproducing, to an almost reverential extent, every nuance and peculiarity of natural flora.

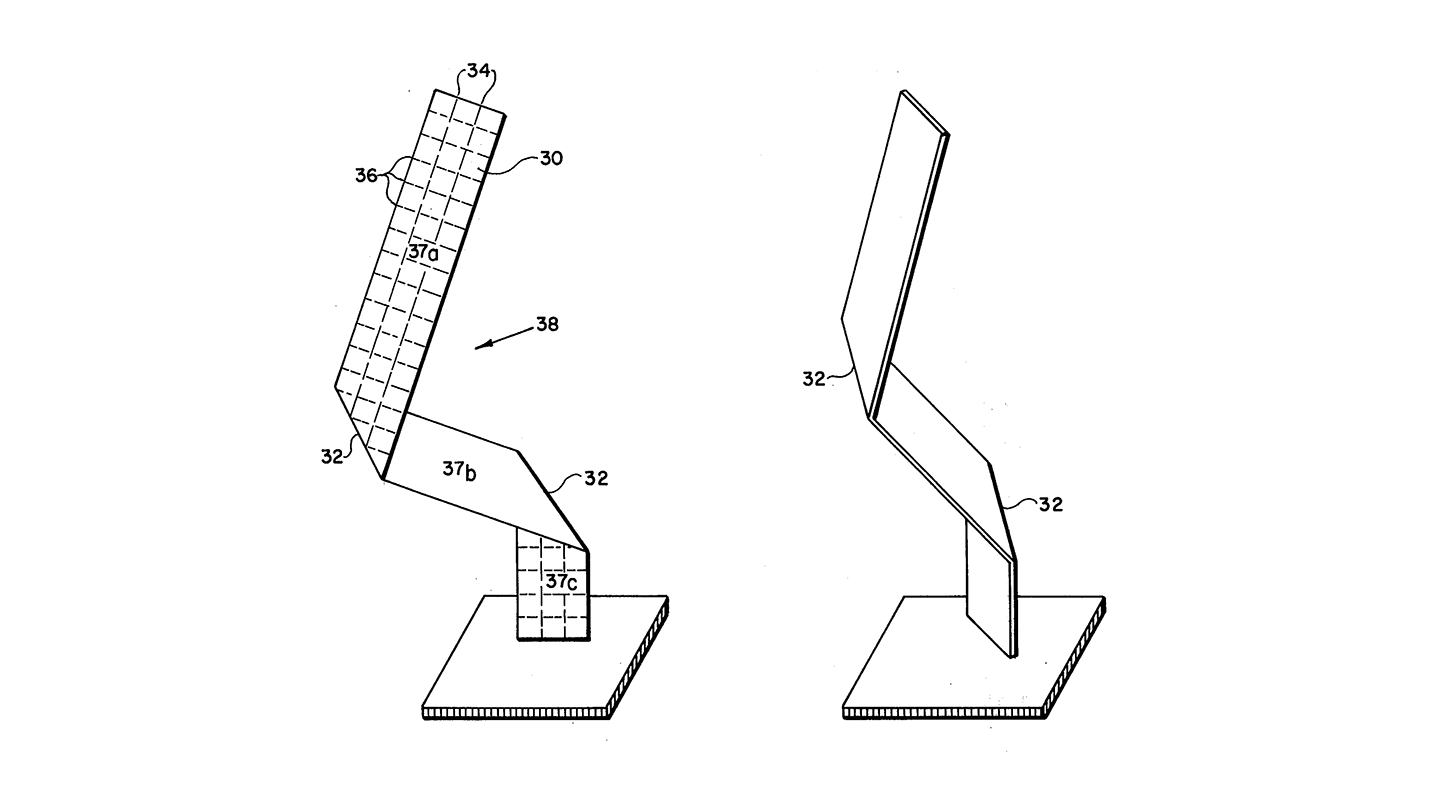

Here, a blade of grass is diagrammed and depicted as one might for a work of sculpture on a pedestal. U.S. Patent No. 4,061,804, “Non-Directional Rectangular Filaments and Products,” 1977

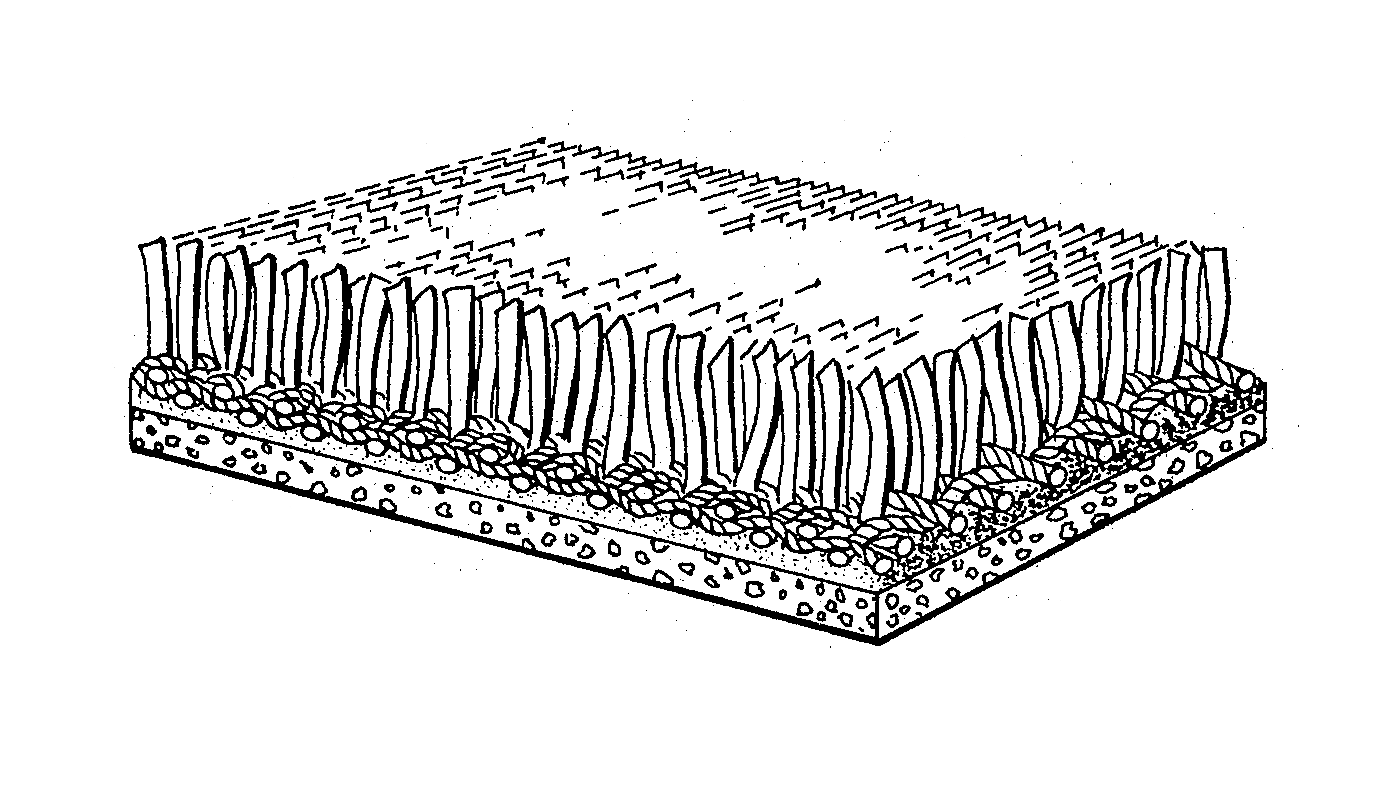

The earliest patents describe the basic process behind manufacturing artificial turf: Small pellets of nylon synthetic polymer, along with colouring pigments (usually shades of green and yellow) and stabilizing additives are heated and extruded into the thin, blade-like strands, or ribbons.

These long strands are then tufted and stitched through a thick backing, generally rubber or latex, and sliced to create the impression of individual blades. The backing is then coated with adhesive and punctured for permeability.

Is it a carpet? Or is it a scrub brush? U.S. Patent No. 3,332,828, “Monofilament Ribbon Pile Product,” 1967.

Over the years, the technological advances centred on perfecting the tufting and structural methods behind the look of the strands, and making synthetics and weaving more durable and resistant to ultraviolet degradation. As digital design and fabrication technologies play a greater and greater role in the production of the constructed world around us, it’s not difficult to imagine a day in which extruded petroleum filaments and layers of synthetic backing can be manufactured in such a way as to blur any easy distinction between fake grass and real grass.

The Origins of Artificial Turf

AstroTurf was developed by chemists at Monsanto in the mid-1960s, the first artificial turf product intended to be not just a cosmetic covering, but an actual substitution for real grass. Research and development in synthetic polymers and stitching techniques made for a surface that could withstand heavy athletic use, outdoor installation and promised performance characteristics “comparable with those possessed by natural turf.”

To a certain extent, the development of artificial turf mirrors facets of our culture in the 20th century. Through the late 60s and 70s, when synthetic turf was just becoming commercially viable, technological specifications focused on the wants and needs of middle-class suburbanites.

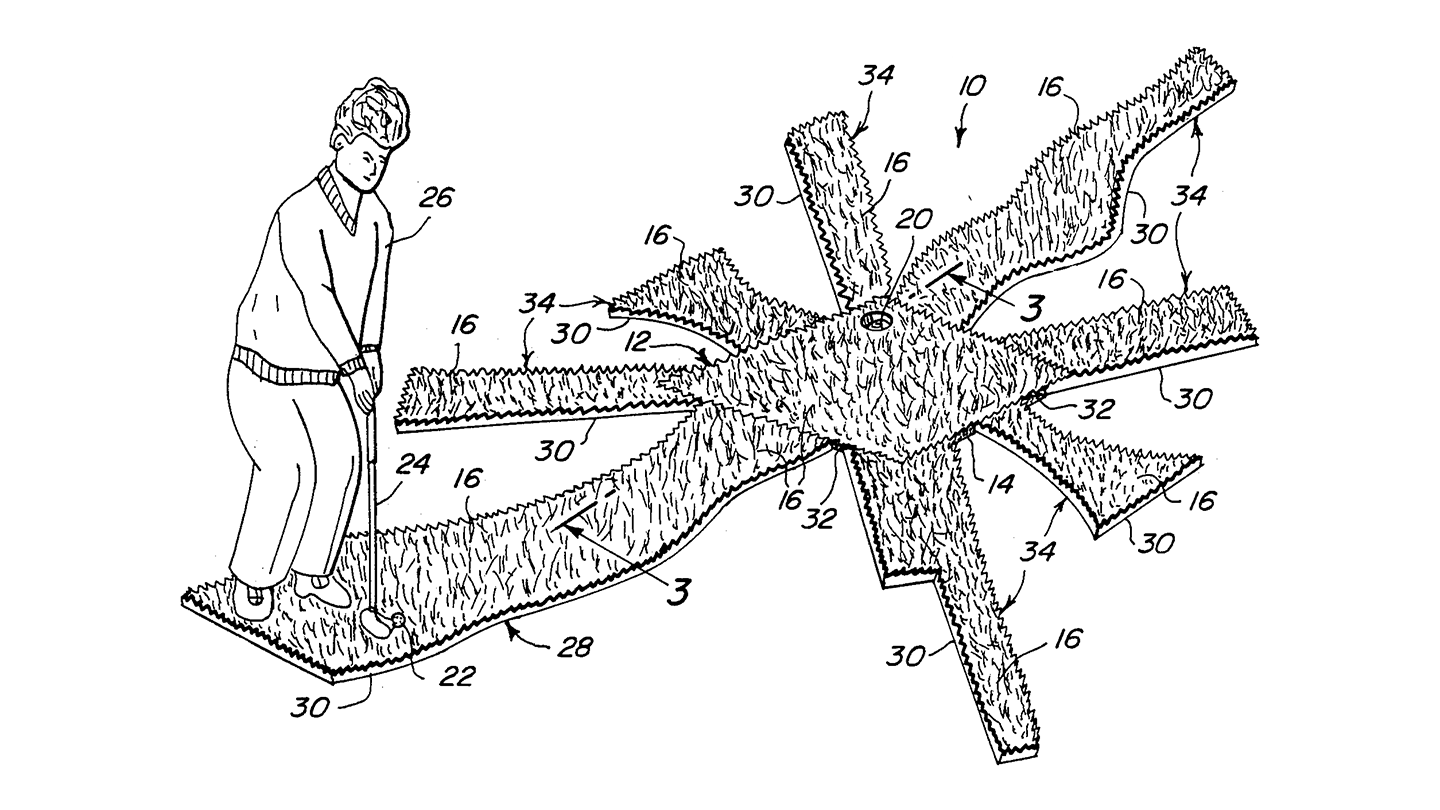

Perhaps no other recreational activity has been so closely associated with middle-class aspirations and professional ambition than the sport of golf. And because of the comparatively small size of the ball in play, the technical challenge of engineering the perfectly performing span of simulated grass was significant.

The stakes were high — and early inventors and engineered devoted meticulous attention on every aspect of the product’s performance. There are patent filings for cigarette burn-proof artificial turf, and systems meant to simulate the challenges of the putting green for those who couldn’t make it to a well-manicured golf course. The use of artificial grass in stadiums and fields took off through the 1970s, after it was used as a replacement for natural turf at the Astrodome in Houston.

The ambition to control and perfect nature while still capturing its richness of variety, captured inUS Patent No. 4,850,594, “Perfect Putting Surfaces,” 1989.

Artificial turf both benefited and suffered from societal and cultural trends that existed around it. AstroTurf entered the market at time when American confidence and enthusiasm for chemistry and technology were surging. In the 1960s, synthetics, plastics, and polymers promised middle-class lives of ease, security and comfort.

But artificial grass soon had to contend with a national sentiment that became far more critical of technology, chemicals, and there implications. The 1970s saw the effects of dioxin by American forces in Vietnam, the burying of toxic waste at Love Canal, and industry efforts to conceal deaths associated with asbestos.

AstroTurf and American Culture

As the changing environment impacts the accessibility and abundance of resources — fossil fuels, plant habitats, and freshwater reserves — it’s worth considering what cultural practices are radically altering, or doing away with altogether. Is a natural grass lawn worth the threat of depleted aquifers? Are facsimile yards worth the expenditure of fossil fuels? Or would we be better off fundamentally rethinking the organisation and distribution of the built environments around us?

In a way, the history of synthetic turf mirrors how we think about nature, wilderness and our domestic spaces. Just consider the iconic suburban lawn.

Our homes provide us with a reassurance of boundaries, shelter, and safety. The grass that so characteristically surrounds the average suburban home is a symbolic gradient between the wilderness of the outdoors and the comfort of the indoors.

Mike Davis writes about suburban lawns as spaces that reveal “the clear-cut, impermeable, but essentially imaginary boundary between the human and the wild” in his book, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster. The lawn softens the metaphorical edges of our walls and roofs, making the stark divide between indoor and outdoor more beautiful.

“The ideal suburb is adjacent to nature,” Davis continues, “but never directly implicated in it.” Perhaps, synthetic turf is a way to make the natural world more stable and predictable — to bring the wilderness under our control. In this case, then, we might say that the artificial landscape could be seen as a more forceful assertion of the uncrossable divide between indoors and outdoors, development and wilderness, or civilisation and nature.

These unnaturally bright green swaths fundamentally change the way we interact with the landscape around us. Historically, that was a labour of nurturing and sustaining living organisms — the plant life that surrounds our homes. But opting for artificial turf changes this work into an effort to maintain something that was mechanically produced.

Instead of watering, edging, fertilising, weeding, mowing, trimming, and cutting, the synthetic yard demands a type of upkeep that is less attached to the ambition to nourish and encourage natural growth, but simply to maintain a product in “like new” condition.

Rather than cultivating a living thing, the focus of work becomes maintaining the perpetual sameness of a factory produced artefact. Artificial lawns are installed, occasionally brushed or sprayed clean and eventually removed to make way for a replacement covering. A typical lifespan for an artificial lawn is 25 years. In many cases, the turf may be subject to a product warranty, or to some other guarantee of satisfaction.

We might agonise the idea of the lawn as no longer a space of clear distinctions and boundaries, whether between drought or flood, indoors and outdoors, or real and fake. But at least we can derive some comfort in the knowledge that the patent drawings for “Real Fake Grass” will probably look amazing.

Top image: AP