Joe Oxenbury was born without a left hand. “It was a glitch,” says his father, Chris. “That’s what the doctors told us. His hand just didn’t grow when he was in the womb.”

When Joe was eight years old, Chris organised a fundraising campaign to buy his son a £2000 prosthetic hand. But children can quickly outgrow their prosthetic limbs — hands need to be updated as often as every nine months to ensure they fit correctly. At that cost, Chris wouldn’t have been able to provide Joe with a replacement as often as he would need.

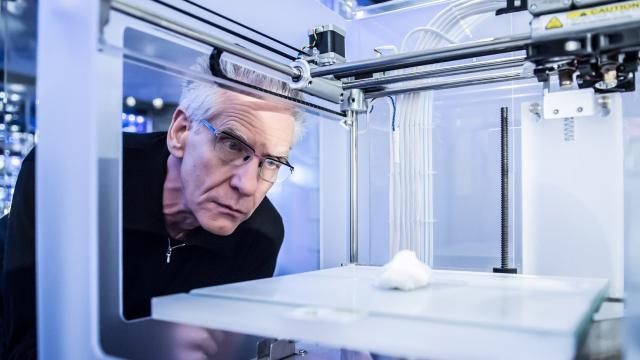

Then, in 2014, Chris read about an organisation called e-NABLE, a 5000-strong international group of 3D-printing enthusiasts. Using open-source prosthetic designs, these volunteers print and assemble prosthetic hands and arms costing as little as £40. Those wanting a prosthesis send through photos, measurements and other specifications. The organisation then matches recipients with volunteers.

“When you get a 3D printer, once the novelty of printing keyrings and trinkets has worn off, you immediately want to do something useful with it,” says James Holmes-Siedle, a London-based architect and the Enable volunteer who made Joe his first 3D-printed hand.

Anyone with a 3D printer can take part, although volunteers are asked to print and assemble a test hand as a show of their commitment and capability to build one. Recipients, however, have to display a certain amount of movement in their wrists or elbows to qualify, since the functionality of the prosthesis very much depends on it. A prosthetic hand, for example, is activated by wrist movement: rotating the wrist forward to open and backward to close.

When Joe’s 3D-printed hand arrived in the post, “within four or five minutes he was picking up oranges and all sorts of things,” says Chris. Joe can now grip a bat with both hands to play rounders at school.

Joe’s prosthetic hand is currently with Holmes-Siedle for repairs owing to wear and tear. Holmes-Siedle sees this as a positive sign — it’s being well used — but it also highlights a limitation: durability. Many volunteers print in polylactic acid, a plastic-like material, which makes the prostheses light enough to attach to the body with a Velcro strap but means they aren’t strong enough to hold larger weights or sustain heavy impacts.

“The technology is great, but the material is not durable enough [to withstand] normal life,” says Dr Abdo Haider, Lead Consultant Prosthetist at The London Prosthetic Centre. Haider uses 3D printing to make prototypes of new prosthetic designs.

Holmes-Siedle stresses that his creations aren’t meant to be full-blown medical prostheses. “They are not prosthetics in the traditional sense. A prosthetist will meet the end client, make moulds, and take very detailed measurements and assessments. We try to be careful about expectations, because that is not what we’re doing.”

What they can do is help kids like Joe, who may have to wait until they are older to suit more costly prostheses. “Because children grow so fast, there might be periods of time when they don’t have constant access to new prosthetics, and this is intended to fill that gap,” says Holmes-Siedle.

One exciting thing about 3D-printed prostheses is that the designs are all freely available open source and constantly evolving. Holmes-Siedle is particularly interested in tensioning, and the fishing wire that acts as tendons in the prosthetic hands. He made some changes to the basic design of Joe’s hand and within minutes of sharing his new designs online, other volunteers around the world were printing, testing and giving feedback on the adjustment. He’s now working on a new revision based on what he’s learned.

Some Enable volunteers are even experimenting with prostheses that are less functional for general purposes but great at one particular thing. “Let’s say you want to ride a bike,” explains Holmes-Sidele. “It’s actually quite difficult to do that with a hand-based product, but it’s easy to have a different [gripping] device on the end that will allow the child to do that.”

Tony McGarry of the National Centre for Prosthetics and Orthotics at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow believes 3D printing also has a lot of potential for low-income and postwar countries where the need for prostheses is rarely met: “There are millions of people who will never get prosthetics, and maybe some day down the line 3D printing might help to address this.”

But perhaps the biggest effect is on children’s self-esteem. The ease and speed of the process mean that it’s easy to design a bespoke prosthesis, different from the usual flesh colours. The first hand Holmes-Sidele made was for a young boy named Charlie, who requested a superhero-themed design. Charlie was later approached by two older boys in the park: “They said ‘Wow, we wish we could have an arm as cool as that!’” Holmes-Sidele’s newest client, a girl, has requested a rainbow theme. Joe went for a steampunk design.

As for Chris, he simply hopes that one day he and Joe will be able to make a hand together: “What I want to do in the future is raise money for myself to get a 3D printer, [and] to give somebody the feeling we had when we opened that box with the hand in it. If I could give that feeling to somebody, it would be amazing.”

This article first appeared on Mosaic and republished here under Creative Commons licence.

Picture: Canadian Film Centre/Flickr