While pundits point fingers at who’s to blame for California’s catastrophic drought, it seems that the state is finally taking one big step towards action. Last week, California’s water board sent a letter to senior water rights holders warning that their rights might be curtailed. But what does this really mean?

The complicated rules that govern the planet’s most precious resource have been challenged in the face of a new and frightening scarcity. Advances in science and technology — like more accurate precipitation forecasts and better ways of tracking use — have allowed countries and states to reevaluate their water policies around the world. Yet in many places outdated and downright archaic laws remain on the books.

So what are water rights? And what do they mean in a time of drought like this? Water rights vary based on jurisdiction, of course, but we can pick a particular place to use as an example. How about California?

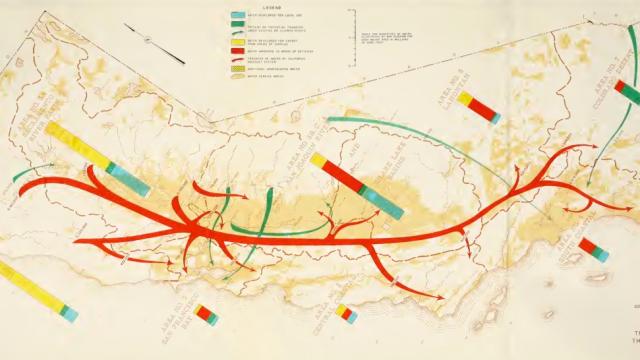

Water infrastructure projects like the San Luis Reservoir are developed by federal or state groups but the water itself belongs to no one. (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli)

A water right is permission…

Water rights used to be very simple. If you owned property on a body of water, you had the right to use as much of it as you pleased, and you could also decide who else could come onto your property and help themselves. But as the population swelled in California during the late 1800s, and growing cities filled with thirsty residents, new laws were needed to fairly distribute water to those who did not have direct access to a source.

The way water rights were established for those who did not own a water-adjacent property was tied to the mining industry. As miners staked their claims they also needed to bring water to the site to process the claim. Whoever made the improvements to help divert water to the claim had first dibs on the water as well.

This way of thinking continued even as larger infrastructure projects like irrigation canals and aqueducts were built. This adage “first in time, first in right” has pretty much guided water rights policy for over a century.

…to use a reasonable amount of water…

Although some water rights still date back to those prospector days (more on that in a second), water and its sources can technically not be owned by anyone anymore, so about a century ago authorities began to control access and allocation. In California, the State Water Resources Control Board decides how much water each rights holder can have — this includes anyone from a small Central Valley irrigation district, to the Metropolitan Water District, which supplies water to the City of Los Angeles. These amounts are called “claims” on water. After many years of little oversight, rights holders must now “prove” their claims by showing how much water they have historically used and how much they plan to use in the future.

…for beneficial purpose.

Here’s the tricky part, and the part that many are contesting in light of the drought. In California, the State Water Resources Control Board issues a complicated array of permits, licenses, and registrations to allow individuals and groups to have water for uses “such as swimming, fishing, farming or industry.”

But many critics believe that irresponsible farming methods to produce climate inappropriate crops or industries like oil extraction no longer qualify as beneficial purpose. Plus the environmental impact of water diversions previously thought to be “beneficial,” like dams, have been reconsidered or even reversed in recent years, changing the water landscape significantly.

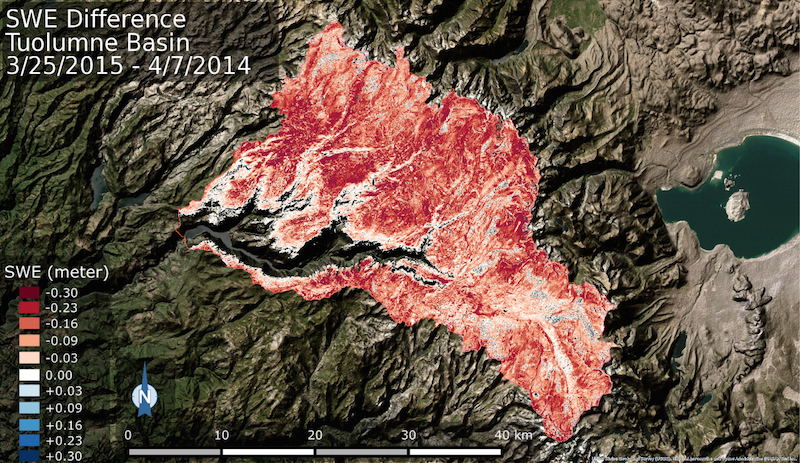

Usually California’s surface water falls as precipitation, mostly as snow. A 3-D composite image map of the Sierra snowpack shows the lowest snow levels in 65 years of record-keeping. (AP Photo/NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Furthermore, there are two kinds of water…

Surface water is what we normally think of when we think of water rights. It includes rivers and lakes but also the man-made reservoirs and other storage facilities that collect the water which falls as precipitation. This is why the reports that California’s snowpack is only at six per cent are so bad — this winter’s snow is this summer’s surface water, and this year, it doesn’t exist.

Groundwater is any water that’s extracted from the ground via a well. This is in many ways a touchier issue when it comes to rights because until last year groundwater rights were not regulated in any way by the state. This has led to years of agricultural interests digging deeper wells to drain local aquifers.

Also, the overuse of groundwater (which is usually only in emergency situations) can ruin the quality of the water table or deplete it entirely. Additionally, many of the groundwater regulations passed for California won’t go into effect for a few years.

…and several different kinds of rights.

To decide who gets precedence in taking available surface water, a hierarchy of water rights has been established by the state. At the very top are riparian rights holders, which are most like the water rights of pioneers: Those with a river or flowing water source on their property have the right to draw a reasonable amount of water from it. (Of course, if that river is very low due to drought, the amount they can take is much lower.)

The kind of rights that most farmers have are appropriative rights, which include the act of taking water to a place that would normally not have any water on it. Appropriative rights in California are further divided into two groups: post-1914 appropriative rights and pre-1914 appropriative rights. These pre-1914 appropriative rights holders gained their rights before the permitting process was set in place in 1914 — their claims are grandfathered in. Along with those with riparian rights, these are the most senior rights holders, who argue their water use should never be restricted.

An irrigation canal normally filled with water is drying up on a farm near Yuba City, California (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli)

How do water rights help farmers?

By knowing where they sit in the priority system, farmers are able to make somewhat educated economic decisions about what to plant. Those who know they are likely to get water can plant more water-intensive crops. Those who might not get as much in drier years can plant more drought-tolerant crops. Some farmers will plant more profitable crops on fields where they have more access to water through senior rights and save other low-yield crops for fields with junior rights.

So what happens during a drought?

When water supply is estimated by scientists to be lower than normal, California’s water board takes an action called curtailing rights which revokes the ability of rights holders to draw their allotted amount of water. This is where the hierarchy comes in, because the rights are curtailed from the bottom up, starting with the most junior rights holders.

Last year California curtailed the rights of its most junior holders. It’s likely that will happen again this summer, and Brown suggested last week that rights for the senior holders might be curtailed as well. A letter that went out to rights holders this week prepared them for the worst: “If dry conditions persist through the spring, it is anticipated that all holders of post-1914 and many holders of pre-1914 water rights in certain watersheds will receive curtailment notices soon.”

Does that mean California is out of water?

No. Just because rights are curtailed doesn’t mean there aren’t more ways to get water. Many cities and municipalities have invested in storage systems which they can use as backup. But many smaller towns that rely exclusively on wells can run out of water if groundwater is depleted, either by drought or by agriculture overtaxing the water table.

Farmers have several options when their rights are curtailed: They can use recycled wastewater from nearby treatment plants, they can pump groundwater (noting the above issues around this), or they can buy water from more senior rights holders. They can also choose to reduce production so they don’t have to water certain fields, although this is not possible for some crops (like almonds) because the trees will die.

Farmer Rudy Mussi installs drip irrigation on his almond farm. Mussi is one of the senior water rights holders in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, where farmers have been accused of stealing water from junior rights holders (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli)

Why are so many people angry about this system?

One of the biggest criticism of the state’s water board in California is that it has handed out too many claims while failing to take other measures that would ensure conservation of water sources. It has been reported that allocations have been granted for five times the amount of the state’s annual supply, yet there are huge accountability issues with tracking how the water is actually used. Some say rights should come with a requirement for farmers to switch to more efficient watering methods like drip irrigation.

Of particular concern is a quirk in the water rights nicknamed “use it or lose it.” If a farmer, for example, doesn’t use all the water he was allocated, his future rights to that water might be revoked. This could cause farmers to waste water just to ensure that they will get rights to the same amount the next year.

Also criticised is the practice of still giving priority to senior rights holders from before 1914. It seems a bit ridiculous to still honour rights that date to a time when California’ population was only 2.5 million and the LA Aqueduct was the only major piece of water infrastructure in the state.

The economic and environmental landscape have changed so dramatically, especially when it comes to farming. But many of the senior rights holders are also very large and powerful entities which could lobby against legislation or bring lawsuits against the state if they suddenly changed the rules.

So can’t we change the way this works?

Hey, that sounds like a great idea! Many people have been pushing for a reformed system that would do away with existing water rights, including establishing a set price for water every year. Australia reformed its water rights after its catastrophic 2000 drought (which has technically lasted 15 years).

Australia’s Water Act of 2007 changed the way that water is allocated to farmers and cities. At the beginning of each year, scientists look at all available water to determine how much each claim is awarded and how much it will cost. Since rights holders know how much water they will get (and that their supply is finite for that year), it incentivises conservation or investments like putting long-term storage systems into place.

While California hasn’t proposed any such changes yet, it would seem that the time is right for some sweeping reforms.

Sources: California Water Impact Network; 100 years of California’s water rights system: patterns, trends and uncertainty; “California warns of deep water rights curtailments amid drought,” SacBee ; “How Growers Gamed California’s Drought,” The Daily Beast ; “A New Water Paradigm for California,” Civil Eats; “The wrong way to think about California water,” LA Times; “Whose Water is it Anyway? California Water Rights, Explained,” KCET