It’s not something anyone likes to think about, but your smartphone — or your laptop, or the battery in your hybrid car — created a huge amount of toxic and radioactive waste. And now we know what happens to that waste in the long term. It returns to the earth, mingles with sludge, and finds its way into clay pots.

The mud that makes up each of these vessels was carefully drawn from a toxic lake in Inner Mongolia, where the sludge from the world’s most prolific Rare Earth Element refineries ends up. It was brought to London, where a ceramicist in a hazmat suit worked to turn it into actual pottery, representing the waste created by a smartphone, a featherweight laptop, and a car battery. Starting today at the Victoria & Albert Museum’s exhibit What Is Luxury?, you’ll be able to see each vase in person — a stark visualisation of exactly what’s involved in building your electronics.

But how do you make a vase out of toxic sludge? The two researchers actually went to refineries in Inner Mongolia, collected the toxic mud, and managed to bring it home, and coordinate the complex project of turning it into art. I chatted with them over email to find out more.

The Poisonous Lake

Kate Davies and Liam Young are the founders of the Unknown Fields Division, a design research group that travels to obscure locations around the world to carry out field research and document these environments.

Last year, the group traced the path of the average gadget backwards across the supply chain. They started with a journey to China’s biggest port on a cargo container ship, and ended at the Rare Earth Element mines of Inner Mongolia, where the metals needed to make batteries for virtually all electronics emerge from the ground.

Film still © Toby Smith/Unknown Fields

You’ve probably never heard the names of most of the Rare Earth Elements in your smartphone, but there are as many as eight in the phone sitting in your pocket. And leaching those tiny bits of rare metals out of the earth creates, on average according to Unknown Fields, 380 grams of toxic and radioactive waste. That’s almost a pound per smartphone. In 2014 alone, one billion smartphones were sold around the world.

These little-known mines are the reason our electronics exist. There’s yttrium, a beautiful silvery metal used to manufacture screens. There’s neodymium, a blueish metal used to make the magnets that go into everything from electric cars to wind turbines. Terbium, a green-tinted silvery metal, is used to make low-energy lighting.

Film stills © Toby Smith/Unknown Fields

You can’t just mine these metals as you would gold or copper. They’re not found as free elements — they have to be refined out of other materials. That process is labour-intensive and waste-intensive, creating huge amounts of toxic and radioactive waste. A single ton of Rare Earth Elements creates an incredible 75 tons of waste water, made up of acids, toxic chemicals, and radioactive waste.

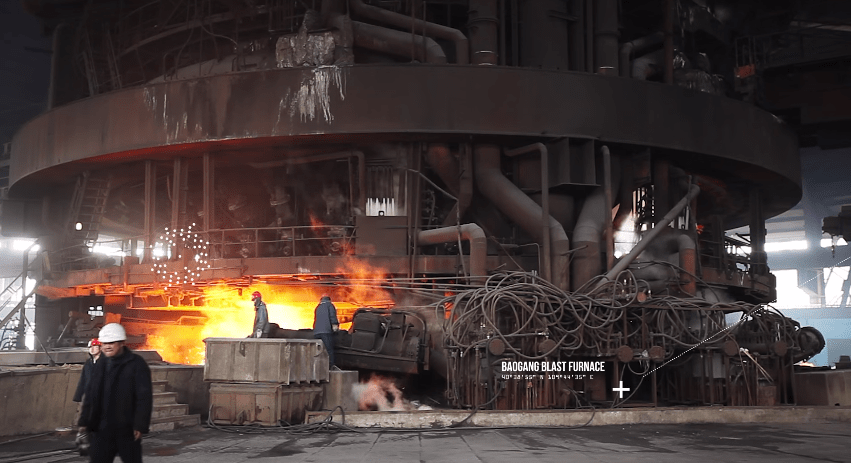

Almost all the Rare Earth Elements refined in our world come from Inner Mongolia — most of them from the mines of a city called Baotou, where Young and Davies travelled last year. Here, the mining process has created a “poisonous lake.” The tailings, or waste, from the refineries has to go somewhere — and it’s here where the thick, black sludge is deposited through massive pipelines.

© Toby Smith/Unknown Fields

Young and Davies were there to conduct research, photographing and interviewing locals in Baotou. But they were drawn to the toxic lake — and ended up carefully collecting the sludge while at its shores. A video from the project shows Young crouching at the edge of the lake, collecting mud while dressed in a bright blue hazmat suit.

That sludge was destined to become part of an exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum that opens this weekend.

Toxic Pottery

If you passed by the pair’s three vases without realising the story behind them, you might think they were simply antiques. They look burnt, as though they have endured hell to get here, and in a way, they have.

When Davies and Young returned to London, they began the process of transforming their vials of mud into pottery. First, they had to figure out exactly how much waste is made to manufacture typical electronics — a smartphone, a super-thin laptop, and a smart car battery. Once they had determined the amount of sludge that each vase would need, they worked with ceramicist named Kevin Callaghan, who was tasked with the unenviable job of actually throwing the toxic mud on a spinning pottery wheel and shaping it with his hands — his carefully protected hands.

“Radiation scientists test the toxic clay collected from the tailings lake and find it to be 3 times background radiation.” Film stills © Toby Smith/Unknown Fields

“At every stage of the process everyone would wear dust masks, gloves, goggles and protective suits when handling the material and any waste has been disposed of via hazardous material routes,” Young told me. “An entire city is built beside this toxic lake in Inner Mongolia yet for us to be safe when handling this material and get past the museum’s health and safety team we all needed full body protection.”

The consistency of the sludge meant that Callaghan had to add thickeners to the mixture to make it shapeable. One plus: The mixture didn’t need to be glazed, because the mud contains so much metal that in the fire of the kiln, it creates its own hard metallic glaze.

Film still © Toby Smith/Unknown Fields

How did Callaghan and the group decide what the pottery should look like? As Davies explains, they’re based on China’s Ming dynasty vases called Tongping, which originated around the 15th and 16th centuries. The reference to the Ming dynasty was intentional. “Ming vases are particularly iconic objects of high value as well as being artefacts of international trade,” says Davies. “A one family global superpower, the Ming dynasty presided over an international network of connections, trade and diplomacy that stretched across Asia to Africa, the Middle East and Europe, built on the trade of commodities such as imperial porcelain.”

In a way, these vases are built on the trade of commodities too — though a very different commodity than those the 15th century world trafficked in.

The Other End of the Supply Chain

Though they’re primarily designers, Davies and Young have way bigger ambitions than most. They want to show you the back alleys and waste products of the global economy by documenting the parts of it consumers rarely see. Their most recent trip was to Bolivia, where they visited the world’s biggest lithium mines.

Pottery seems like a pretty anodine way to get peoples’ attention about the side effects of their technology. And yes, the vases are, like most pottery, functionally useless — they’re mean to be seen and admired. But they’re also dangerous. To go along with the vases in the exhibition, the duo had to engineer protective cases to make sure none of the material flaked or otherwise exposed bystanders. “I like the idea that the vase might sit in the home next to someone phone, the latest gadget sitting next to its shadow,” Young writes. “If we choose to live with the technology then we must be ready to live with its consequences.”

What will happen to the vases once the show ends? It’s unclear. Would you want to live with a radioactive mud vase in your home? As Davies points out, you’re already living with the gadgets that are the reason the sludge — or the toxic lake — exists at all. “They are presented as objects of desire, but their elevated radiation levels and toxicity make them objects we would not want to possess,” she writes. “They represent the undesirable consequences of our material desires.”

Pictures: Toby Smith/Unknown Fields