It’s weird to see a working Nest thermostat on display at a Smithsonian museum in Manhattan. It’s even weirder to tinker with the gadget, pushing buttons and changing settings. But touching and tinkering with technology is the Cooper Hewitt future museum’s specialty.

You could consider the Cooper Hewitt to be the Smithsonian’s computerized crown jewel. The century-old design museum recently finished a three-year-long renovation that gutted the Gilded Age mansion that once belonged to Andrew Carnegie and, perhaps more importantly, completely reinvented how a Smithsonian institution deals with data.

Put simply, the Cooper Hewitt put its entire archives online, free for anyone to view, and employed 21st century technologies like NFC and touchscreens to give visitors more access to that data than ever before. The whole experience is rooted deeply in an elegant open API and guided by a custom-built “pen,” a magic wand of sorts that lets you interact with every single object in the museum.

Building the museum of the future isn’t just about tossing a bunch of technology into an old mansion, though. The Cooper Hewitt’s own museum futurist, Seb Chan, recently explained to me how it’s as much about a change in philosophy as it is a question of technology. And when I found myself playing with historically important gadgets, sending data about exhibits to a personalised webpage, and watching a robot draw my face in sand, I started to understand what he meant.

The House That Carnegie Built

Just a few blocks from the Guggenheim, the Cooper Hewitt sits on a conspicuously lush patch of land like a country home that got stuck in traffic on Fifth Avenue. This was Andrew Carnegie’s intention. The cherub-cheeked steel magnate picked the far uptown location so that he’d have enough land for sprawling gardens. Nevertheless, it wasn’t the landscaping that set this mansion apart from the rest. It was technologically advanced features like full electricity, an elevator, and climate control.

When the Cooper Hewitt took over the space in 1970, amenities like these had become pretty pedestrian (except for the elevator). The spirit of innovation stuck around the house, though. After all, the museum had been founded by the granddaughters of American industrialist Peter Cooper on a forward-thinking idea. Museums shouldn’t be designed to preserve precious objects. The more heroic mission should be to preserve the information that those objects possess. It’s a perfect mission for a design museum, when you think about it.

That mission endures at the Cooper Hewitt to this day. As part of its massive overhaul, the museum put every single object in its collection of over 200,000 objects online. The collection is sorted by people, by country, and even by colour. Each object gets a permalink, a detail that’s central to the new pen (a.k.a. “magic wand”) and the visitor’s ability to save details about their experience to web. All of this information, Chan says, is the property of the American people.

Because Information Wants to Be Free

When I met Chan, he was wearing bright orange shoelaces and an even brighter smile. The Australian data evangelist, technology enthusiast, and former DJ came to Cooper Hewitt after a stint at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney. (They have an API, too.) Chan now heads up Cooper Hewitt Labs, a small team of visionaries that includes former Flickr engineer and digital artist Aaron Straup Cope. As we walked around the museum, we spotted some of the Cooper Hewitt Labs team dissecting the software on one of the museum’s new touchscreen table tops. It almost looked like they were tweaking an instrument panel on a space ship.

It was an exciting day for Chan and his team. That morning was the very first time Cooper Hewitt visitors could make use of the NFC-enabled pen. The cigar-sized piece of technology is linked to each individual’s unique ticket data and its corresponding spot in the Cooper Hewitt databases.

When you’re walking around the exhibitions and find a pretty thing that you want to learn more about, you just tap the pen on a special “+” sign by the placard. That basically bookmarks the object’s permalink so that you can look back at your list of favourite pretty things after you’ve left the museum.

“Giving every visitor one of these flips their expectations,” Chan told me, holding up the pen proudly. And it immediately made sense to me. It’s kind of like an anti-audio guide since it compels you to interact with the exhibits.

I’m a desperate museum-goer, the kind of person who takes a notebook to an art museum so that I can write down the dates of my favourite paintings and research the time period when I get home. In the smartphone era, I’ve been taking pictures of placards, intending to circle back to my favourite exhibits. I’m also a button pusher. When I go to a science museum, I want to see how things work. If there’s a Van de Graaff generator, I want to touch it so I can feel the static electricity pulse through my body and make my hair stand up. I’m desperate for more information, more interaction.

The Cooper Hewitt delivers on both fronts. This idea of appealing to museum-goers’ potentially infinite curiosity and interactivity is central to the whole experience. Chan said that the new design was supposed to make the Cooper Hewitt more “useful.” He said the challenge was “making it an experiential space and not an informational space.”

A Museum You Can Take Home With You

At first I thought Chan had contradicted himself. Wasn’t the Cooper Hewitt supposed to showcase the Smithsonian’s information, the information that belongs to all Americans? Then what’s the deal with redesigning the museum around some half-baked concept of an experience?

Turns out, it’s a pretty good deal. Tickets to the Cooper Hewitt aren’t exactly cheap at $US18 a pop, but of the information about the collection is free and online. You can look through page after page of beautiful chairs and unusual handles and crazy wallpapers from the cheap comfort of your own home. If you want to sit in one of those chairs or hold one of those handles, you can buy a ticket and do just that. The museum makes it worth your while, too, with interactive features that eclipse any other museum I’ve ever visited.

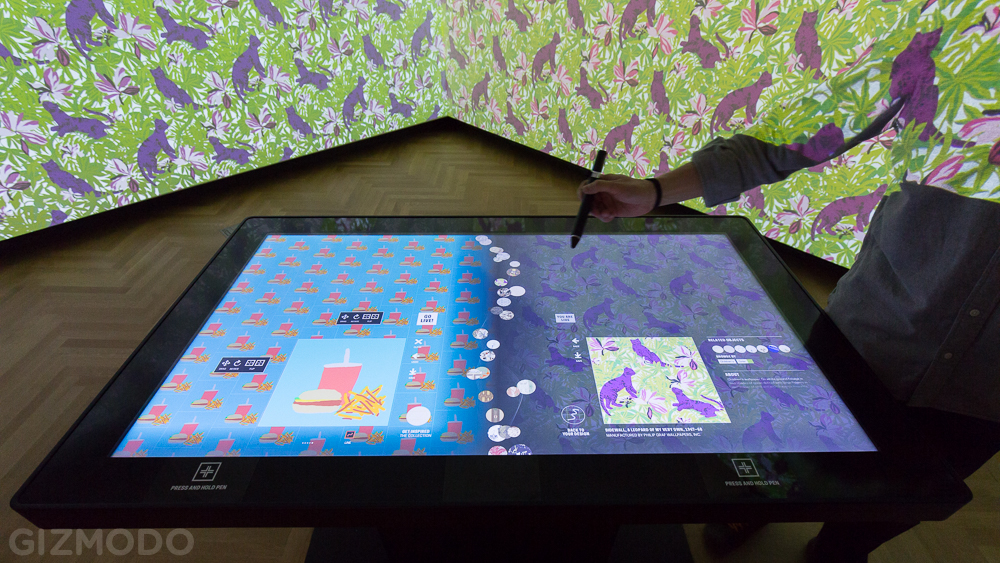

Take the Immersion Room, for instance. This got a lot of buzz when the Cooper Hewitt initially reopened back in December. The Immersion Room is a windowless chamber with giant projectors that display the museum’s huge collection of wallpaper. Instead of staring at lonely strips of paper, the technology shows you what the wallpaper looks like in its native habitat. You can even create your own wallpaper, save it to your collection, and share it with your friends.

Then there are those tables. The pen isn’t just an NFC reader; it’s also a capacitive stylus that works with these massive touchscreen displays. You can browse through the Cooper Hewitt’s collections not only by searching for your designer but also by drawing shapes with the pen. Using the museum’s robust API, the table then finds objects in the collection that are that shape. It also gives you the ability to draw an idea and turn it into a concept. Chan made a squiggle with the pen and quickly turned it into a rather attractive lampshade.

I’d read about all of these things before I got the chance to visit the Cooper Hewitt. It sounded like buzzworthy but ultimately run-of-the-mill interactive exhibits I’ve seen (and forgotten about) at other museums. There’s something about that pen, though.

There’s something exciting about this idea that your visit to the museum will be saved in a database that only you can access — and you can easily delete if you so choose. It’s like a digital shoebox of your favourite pretty things, some of which you created.

By the end of our tour, I was sold. The Cooper Hewitt Labs crew doesn’t just want to change how their museum works. They want to change how all museums work. That’s probably why they explain all of their projects in detail on a blog and became the first museum to waive all copyrights to certain pieces in its collection through a Creative Commons “CC Zero” licenses.

I did shutter a couple of times, when he talked about how the museum was designed to be selfie-friendly. There were even signs that said “Photography is encouraged” with a special note: “No Selfie Sticks But Selfies Are Fine!” Good call on the selfie stick ban, but selfie-takers don’t need that kind of encouragement.

Then I got a little less grumpy and realised that the selfie stuff acted as a rather poignant metaphor for how Cooper Hewitt is changing our whole conception of a museum visit. Just as social media makes everything about you — sometimes to a damaging degree — this Smithsonian outpost is trying to personalise the museum experience. And while I think this selfie trend is pretty obnoxious, a lot of people like it. People like remembering where they have been, and they love showing their friends. The Cooper Hewitt experience is designed to make those two things easier, all while opening up access to information for everyone. All museums should work like this!

After I said goodbye to Chan, I wandered into the “Beautiful Users” exhibition. This is where I found the Nest. Nearby, I saw the first laptop ever invented — invented by former Cooper Hewitt director Bill Moggridge, nonetheless. Moggridge, the founder of the legendary design firm IDEO, coined the term “interactive design.” Moggridge is the one who said, “It doesn’t occur to most people that everything is designed — that every building and everything they touch in the world is designed.”

I was thinking about this idea, as I stood there tapping away on the Nest. What earned this futuristic thermostat a spot in a Smithsonian exhibit isn’t merely the fact that it’s pretty. It’s there because it’s useful. The half-century old Honeywell Round thermostat on the wall next to the Nest is there for the same reason: good design. You’d expect as much at a design museum.

It wasn’t until the next day that it all came together. Moggridge was the director of the Cooper Hewitt from the early stages of the renovations until his death in 2012. His legacy is everywhere still. In his deeply influential book Designing Interactions, the late luminary wrote:

What makes humans special first and foremost is that we can model the world, and we can predict the future. Then we can imagine the future.

When you think of the Smithsonian, you probably don’t usually think about the future. But the Cooper Hewitt is doing something refreshingly futuristic. It’s enlisting technology to make information more free. It’s also making the experience of a museum visit not only less fleeting but also a little bit immortal.

Imagine if all museums did this…

Pictures: Michael Hession