One of the greatest media experiments of the 1930s and 1940s was the faxpaper. Almost entirely forgotten today, it was a technology that could deliver newspapers over the radio waves, then print them instantly right in your home.

When we think about the evolution of mass media, it usually goes something like this: First came newspapers, then radio, then TV, then the web. But that’s not how technology actually progresses. It usually proceeds in fits and starts, with some ideas born far too early — and then adopted decades later as if they were new. Such is the case with faxpapers.

People of the 1930s were starting to think of the newspaper as an old fashioned news delivery device. Despite the Great Depression, the radio was one of the few new technologies to achieve mainstream success (that and the mechanical refrigerator) at a time when American budgets were stretched thin. So newspapers tried to develop new ways to compete.

Enter the radio faxpaper, a technology that was embraced by at least two dozen newspapers in the United States in the 1930s and ’40s. Newspapers often went so far as to buy their own radio stations to make this happen. But this exciting new media experiment couldn’t find its footing in a world of rapid technological change.

Bite-sized news beamed through the ether

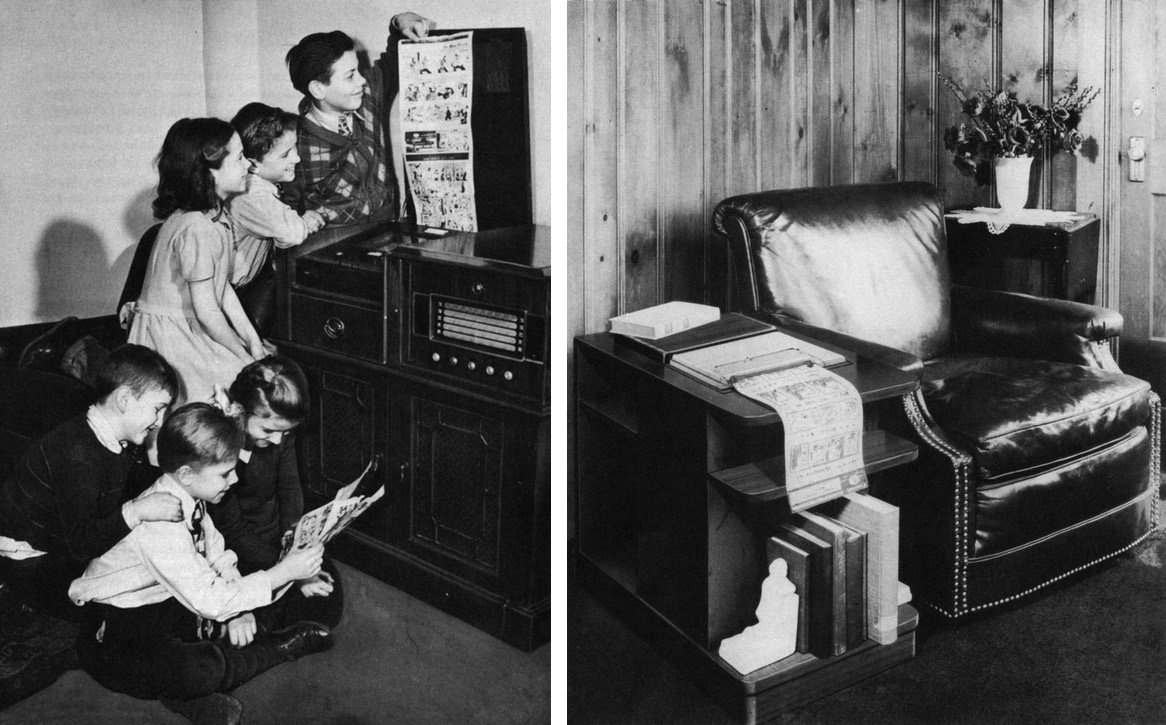

Kids watch the comics section of a faxpaper being printed on a home receiver (left) a chair-side faxpaper receiver from Alden Products Company is displayed (right)

The vision for the faxpaper was about delivering condensed, image-heavy versions of the news as fast as possible. Sound similar to the mainstream media’s immersion into the world of Twitter, Tumblr, and Snapchat? It should.

I spoke with Noah Arceneaux over the phone about the forgotten history of the faxpaper. He’s an associate professor of media studies at San Diego State University and author of the definitive paper on the subject. Arceneaux sees plenty of parallels to the challenges facing the newspaper industry in the 21st century.

“It’s very similar rhetoric we have about printed newspapers today. People realise that there’s just this slow distribution process,” Arceneaux tells me. “You can’t get information immediately about a fire or say a coming storm or anything that’s immediate.”

Faxpapers were supposed to change all that. They would be both a supplement to the daily newspaper and a complement to the increasingly popular radio broadcasts if they played their cards right.

“The radio facsimile newspaper wouldn’t be truly immediate, but faster than waiting for the next morning to get a printed newspaper,” Arceneaux said. “So I think that was the impetus, that we can deliver news to people very, very quickly and we can provide supplemental information that we can’t do purely through oral radio.”

A faxpaper machine for every home

Front cover of the April 1934 issue of Radio-Craft magazine

The trials of newspaper radio fax would start in earnest during the early 1930s. Companies like RCA and inventors like William Finch dove in, experimenting with different ways to transit newspaper pages over the air so that they could be printed in the home.

But the tinkerers and inventors were always beholden to the whims of the Federal Communications Commission. And often for good reason. The broadcasts for faxpaper delivery were so shrill and noisey that the FCC almost immediately banished them to the late night hours, so as to disturb as few people as possible who might accidentally tune in to the experimental stations on their regular sets.

The newspapers who had taken up the experiment spanned the entire country, from the Dallas Morning News in Texas, to the Cincinnati Times-Star in Ohio, to the Radio Bee in Fresno, California. All of the publishers of these faxpapers already owned newspapers or radio stations. But as the tech behind faxpapers looked more and more promising, other companies wanted in on the action as well.

As Arceneaux points out in his paper, there was one company in Jackson, Michigan that was more or less starting from scratch, without the infrastructure of content-producers like a radio station or newspaper. The Sparks-Withington Company opened their station in 1938 and had big ideas about selling faxpaper receivers to Americans. But their enthusiasm would eventually wane. Like other receiver manufacturers, by the end of the 1940s they would focus on television as the more promising technology of the era.

At the end of the 1930s, as World War II was becoming an urgent concern in the U.S. even for isolationists, there were 18 stations that had approval from the FCC to deliver faxpapers over the radio. Both Finch and RCA would have radio faxpaper machines on display at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and people were relatively certain that with some improvements faxpapers could be a real contender. But as we might expect with the benefit of hindsight, their experiments would draw fewer oohs and ahhs than that other futuristic technology on display: Television.

Faxpaper departments and college courses

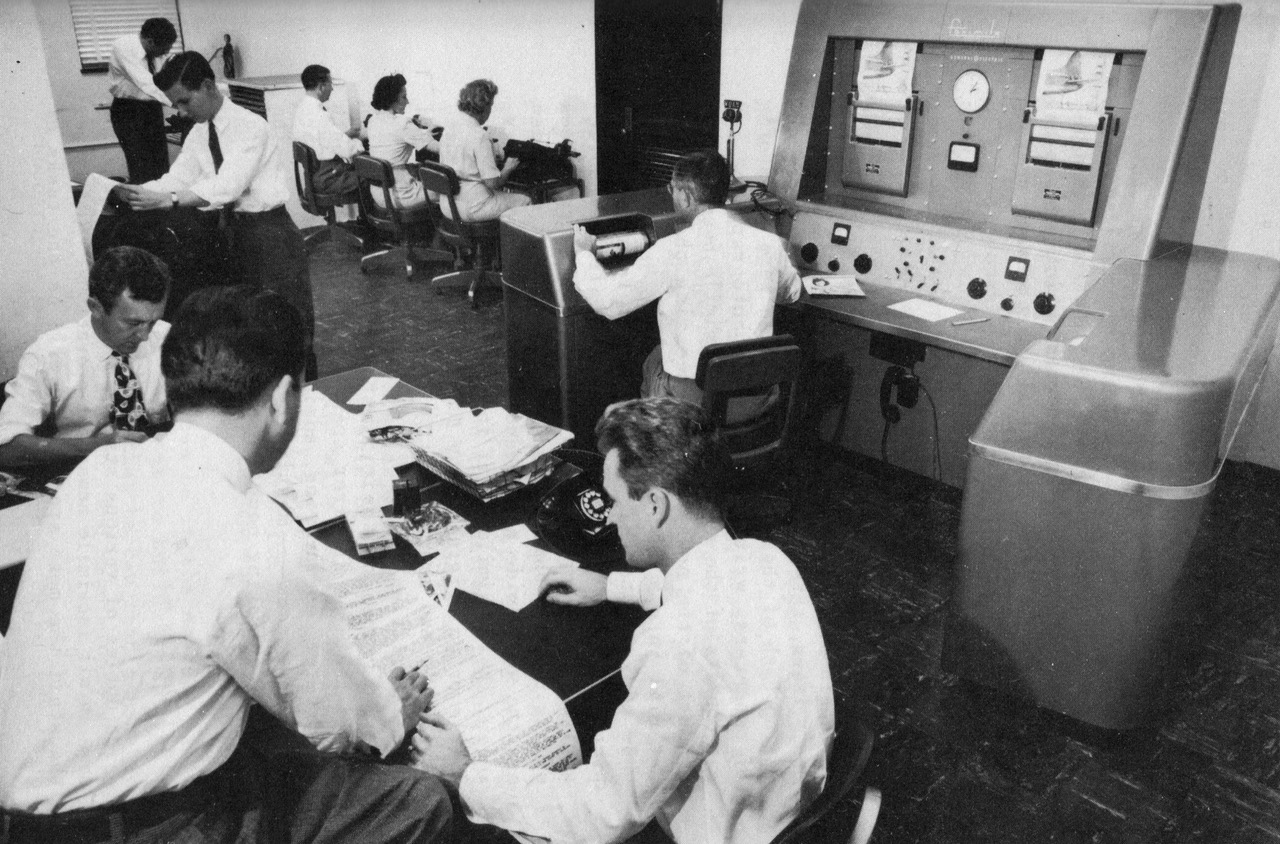

The Miami Herald’s faxpaper department circa 1948

With successful trials of faxpaper delivery humming along, newspapers of the early 1940s had to seriously consider whether this might be the future of their industry. Newspapers like the Miami Herald took it so seriously that they even had an entire team devoted to just the faxpaper, complete with a Facsimile Editor, Timothy J. Sullivan.

The Miami Herald even released a textbook on the subject in 1949 simply titled Facsimile. And not so coincidentally, the University of Miami also started teaching a course in “facsimile journalism.”

The editors of the Herald bragged that even though the students in the faxpaper class had some training in journalism, none had any idea about radio. After just nine months, all of the students “including three girls, were competent to operate the equipment and apply their journalism training to facsimile’s special requirements.”

But much like the anxiety over teaching technologies today, there was reasonable concern that their training would fast become obsolete. That was simply the price you paid for being on the cutting edge of new media.

Visual aides for radio shows

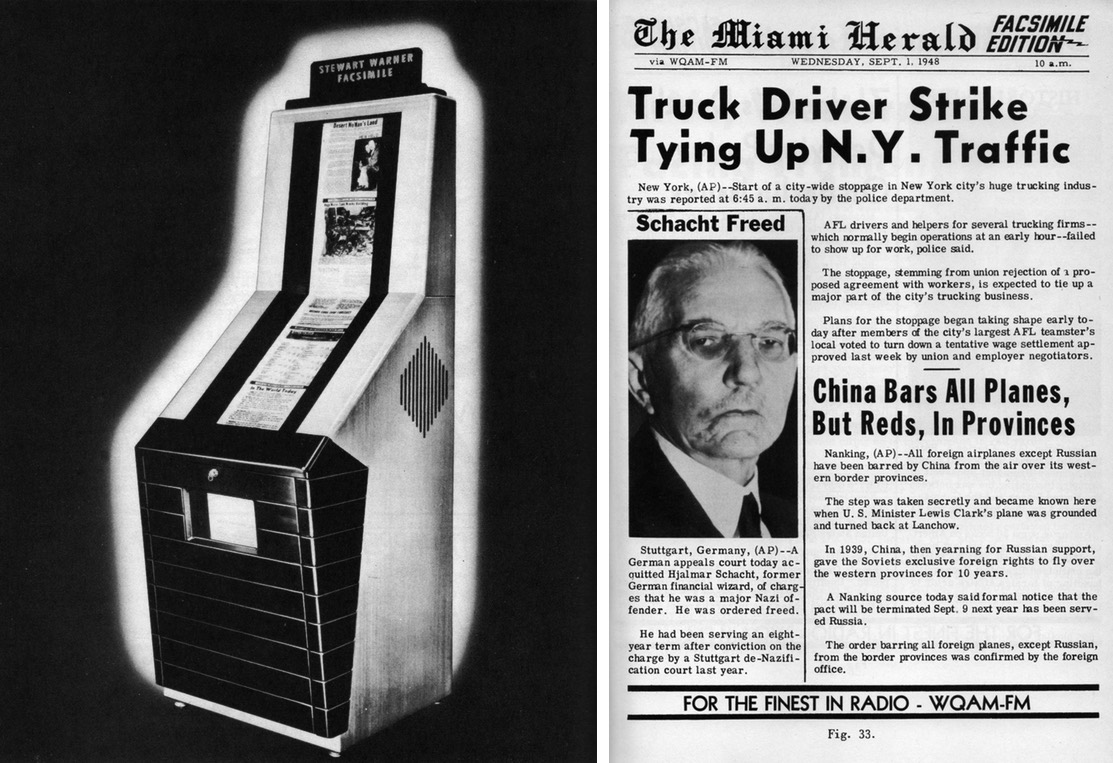

A woman demonstrates a faxpaper receiver made by the Stewart-Warner Corporation

One potential use for a faxpaper delivery system would be to illustrate certain aspects of a news story that were difficult to describe. Faxpaper grew up in the middle of fighting in Europe and the arrival of World War II, so war news was a natural touchstone to describe how faxpaper might be properly exploited to keep people better informed.

“While a commenter in London is giving a play-by-play account of a crisis involving the countries of central Europe, the facsimile station can send maps and photographs to illustrated the areas and personalities involved,” the 1949 book by the editors of the Miami Herald explained.

The ways in which the radio experiment could be enriched and complemented seemed never-ending. Say you had a cooking show on the radio and wanted to give people a recipe. The most common way that this is done in the 21st century seems to be driving people to a website. But back in the 20th century, people were often encouraged to grab a pencil and paper. With faxpaper tech, the recipe could be sent directly into the home while you’re enjoying the cooking show.

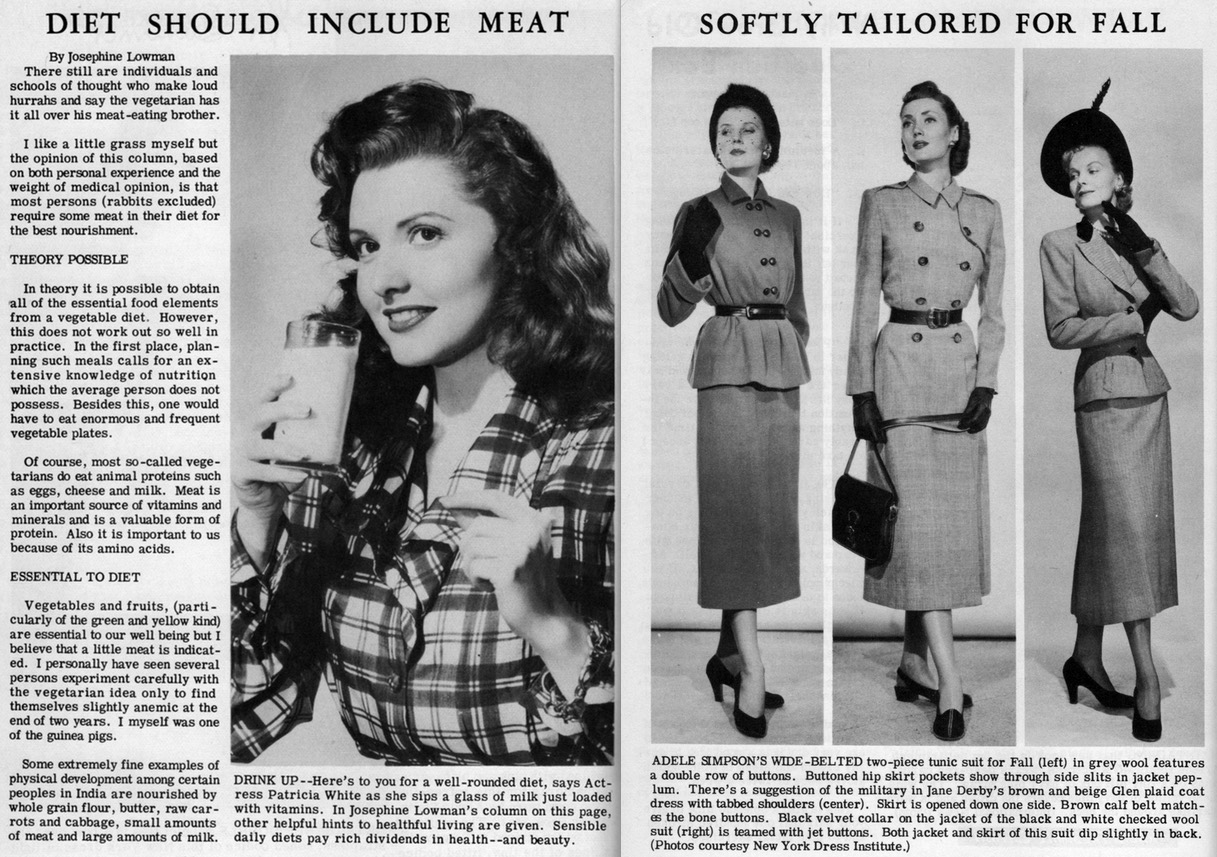

Sample faxpaper pages scanned from the 1949 book Facsimile by editors at the Miami Herald

Arceneaux explains to me that you could even send people a pattern for a dress, “and then they could sort of follow along with someone on the radio” as they were making it.

The book also described a day when the President might be delivering a speech and the full text of the speech would be printed off for future reference. When newspapers of the time were asked by advertisers why they should advertise with deadtree media rather than radio the first answer was generally about the ephemeral nature of the radio. If a listener was only half paying attention or missed something an announcer said, there was no way to rewind the broadcast. Faxpaper tech was supposed to fix all that.

Paper, be it the president’s speech or an ad for cornflakes, was tangible. People could hold it in their hands and properly study the message that the advertiser was trying to deliver. Or at least that’s what the newspaper publisher wanted advertisers to envision.

But how do you pay for it?

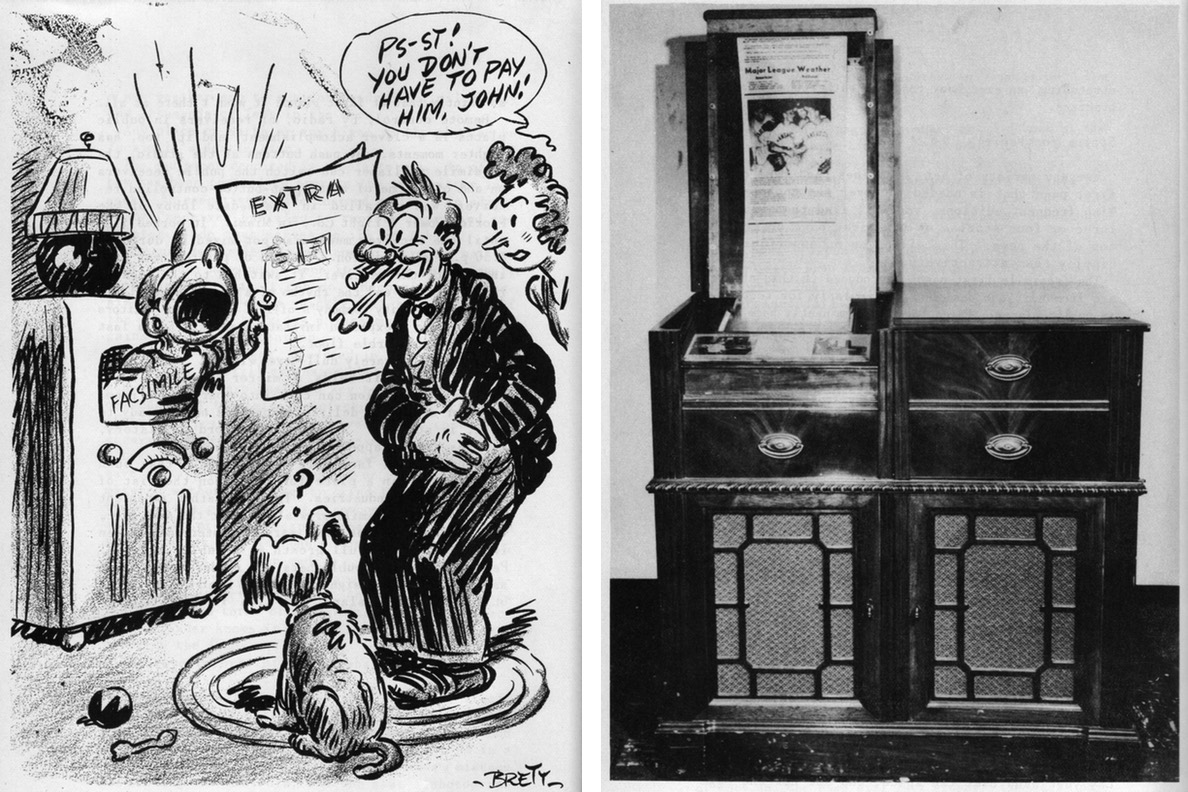

Cartoon poking fun at the idea that you don’t have to pay for faxpapers (left) Top of the line General Electric faxpaper receiver with plexiglass-covered display column (right)

The faxpaper receivers were pretty expensive. You could pick one up at Macy’s in the late 1930s for $US100 — about $US1600 adjusted for inflation. But the nicer RCA receivers could cost over $US220, or about $US3600 adjusted for inflation.

However, once you bought one, there was no way for the newspapers to regulate who could or couldn’t get their faxpaper transmissions — just like the radio. So just like commercial radio in the US, they would have to depend on ads. The big problem at first was that the FCC had to grant permission for that to happen.

Sponsorship and native advertising

Public faxpaper kiosk designed by Stewart-Warner Corporation (left) Sample Facsimile Edition of the Miami Herald (right)

The FCC began allowing radio faxpapers to officially carry advertising in 1948. With that, even commercials could be delivered as printed ads for a double punch of sponsorship.

There were also entire sponsored editions of faxpapers imagined. Think of it as the sponsored blog posts of the 1940s. The book explained that it would be perfectly natural to have a travel edition of the faxpaper sponsored by airlines, railroads, travel agencies or even oil companies. Such editions would naturally be very image-heavy, with maps, schedules and plenty of pictures showing enticing destinations or accommodations.

But all these dreams of faxpaper advertising were dead on arrival. By the time that the FCC allowed faxpapers to advertise, the technology was already on its way out. There were just a handful of stations in the country still dabbling with the tech by the end of the 1940s.

Even if it had survived into an era of faxpaper advertising, the technology still had significant hurdles to make it viable for mainstream consumer use. One struggle? It could be incredibly messy. Arceneaux shared a story with me about his time at the National Archives, digging into this story for his 2011 paper in the Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media.

“When I was looking at one of these faxpapers — it was a long thin ribbon — and the back of it was completely black, like carbon paper black,” he said. “And as I was looking at it […] after like 10 or 15 minutes my fingers were so black that I had to go to the bathroom and wash them. And I did that a couple of times that afternoon.”

“If this is doing this to me in 2010, how bad was it in 1940? I’m guessing these printers may have been pretty messy — spilling ink and spitting out ink, so I’m guessing people didn’t want these in their living room.”

TV kills the faxpaper star

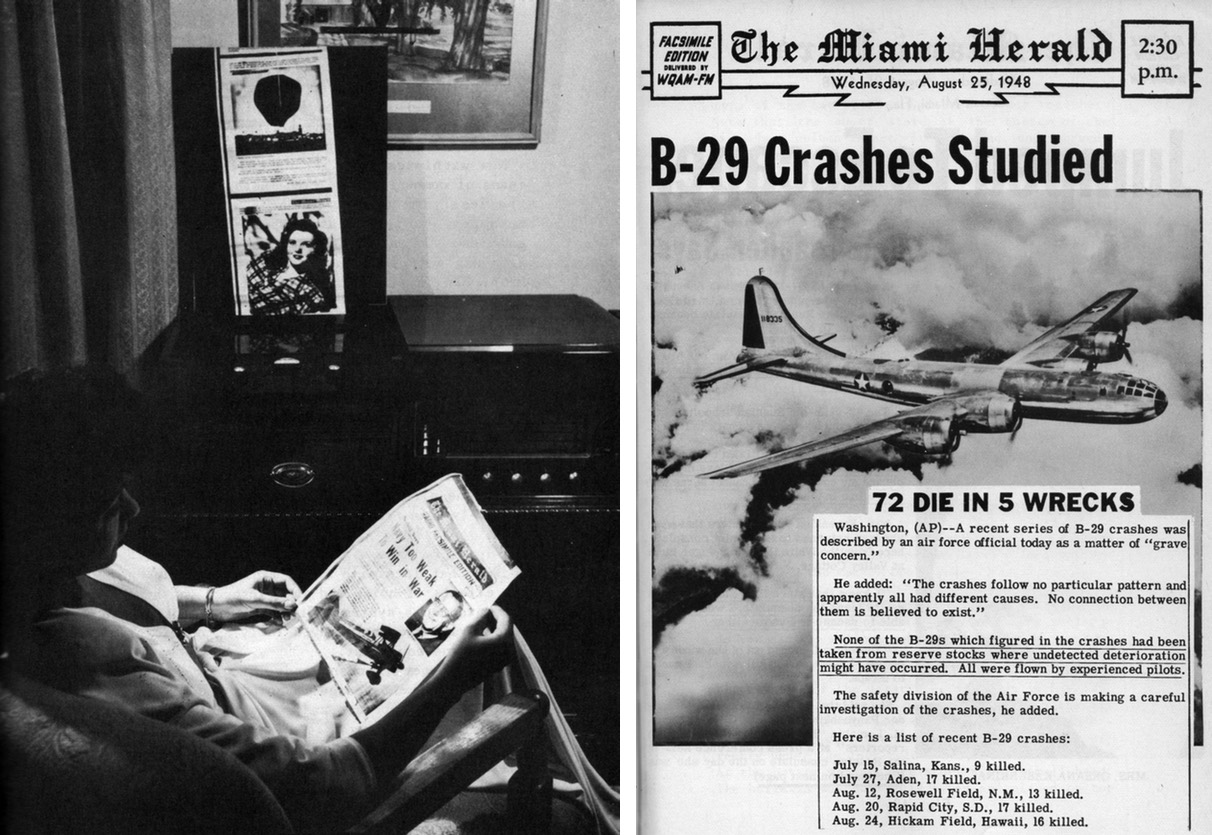

A woman reads a faxpaper in her hotel suite (left) The afternoon edition of a faxpaper from the Miami Herald (right)

So what else led to the downfall of this once-promising technology, aside from everyone’s hands being awash in ink? Price was certainly one major issue, with receivers and paper for them costing so much. The delivery speed was another. What had been envisioned as a way to delivery news incredibly rapidly was far from instant.

“There were some papers that were transmitted overnight and it’d take three or four hours to get a couple of pages. It was just really slow,” Arceneaux tells me. “And they never brought the technology to the commercial mainstream, which maybe could’ve solved the cost problems or streamline the operation. ”

At three to four hours for printing, you may as well go down to the corner store and pick up a newspaper that had been printed four hours ago. The promise of television, still relatively primitive in the late 1940s, was just too enticing for early adopters.

“While that was going on in the late 1940s people could buy a television. And if you went to a department store and you saw the two products side by side, it’s clear. Why would I buy a facsimile receiver when a television gives me live, moving images?”

Why indeed. And Americans did just that. In 1949, just 2 per cent of Americans owned a TV set. By 1955 over 60 per cent of American households had a TV.

It’s fun to think of what the second half of the 20th century might have looked like had faxpapers overcome the technical and regulatory hurdles that kept it down. Radio faxpapers are the futuristic tech that nearly changed the world. But history has relegated it to the forgotten crack in between humanity’s jump from radio to TV.