I’m going to try to convince you that if you have a budget DSLR slung over your shoulder, there’s a high likelihood that you’ll be better served by a point-and-shoot camera. Weird, right? But hear me out.

Shuttered

You remember the old point-and-shoot you lugged around in the mid-aughts? You ditched it for the camera in your smartphone, which was a good move! The migration started around the time of the 2010 release of the iPhone 4, even before smartphone cameras were legitimate replacements. The convenience of your phone trumped the nuisance of a standalone point-and-shoot that produced images that were only marginally better in a layman’s eyes.

None of that’s news. You’ve lived it yourself. Thanks to a new breed of point-and-shoots, though, compact standalone cameras are making a comeback. And what they’re able to replace aren’t the smartphones that conquered them before, but a technology that’s become as outmoded as your Canon PowerShot was three years ago: the budget DSLR.

The consumer versions of the once professional-only DSLR sprang up about a decade ago, and in that time they have become nearly ubiquitous. Their rapid adoption made sense at first; their large APS-C sensors far outshone the point-and-shoot alternatives. But while DSLRs still take better photos than smartphones, evolving technology in compact mirrorless cameras has made it easier than ever to find similar high-end image quality in a much more convenient package.

DSLR sales are slowing down, but not as fast as you would expect. But let’s draw a line in the sand. You don’t need to shrink down you expectations just because you shrink down your camera. Camera size no longer equals quality. I’m not saying go mirrorless. In fact, I’m saying go smaller. Go point-and-shoot.

Resurrection

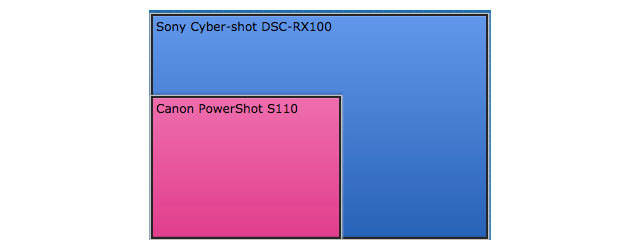

You can trace the return of the point-and-shoot directly back to 2012, with the original Sony RX100. The compact camera looked like a slightly larger version of more refined point-and-shoots that started popping up about five years ago, around the time the smartphone conquered all. But under the hood, the RX100 had a one-inch image sensor, much larger than its predecessor. Just look at how much bigger the RX100’s sensor is compared to Canon’s leading tiny, cheap point-and-shoot of the day.

Bigger image sensor, better image quality. Picture: Image Sensor Comparison Tool.

The RX100 and its two successors have been (rightly) very successful, and that success has inspired a copycat: The new Canon G7 X is basically a variation on the same design. One-inch sensor, integrated zoom lens, tiny body.

And these two aren’t alone in the new wave of large-sensor compacts. A certain strain of street photographer might opt for the Nikon Coolpix A or a Ricoh GR, two tiny fixed-lens cameras that have APS-C sensors — exactly the same size chip as the DSLRs ambitious amateurs have been slinging around for a decade.

Panasonic has followed suit, replacing its LX cameras with the larger, but not huge, LX100. This camera has the micro four thirds sensor found in Olympus and Panasonic mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras. It’s not quite as large as an APS-C sensor, but it’s far larger than a traditional point-and-shoot format.

All of which is to say that if you’re carrying around a DSLR because you want better images than what you can get from smartphones and point-and-shoots of yore, that’s totally understandable. But what you really want is one of the cameras I just listed. They all meet the minimum requirements: They take take great photos, much better than your smartphone or cheapy point-and-shoot. Plus, they’re easier, lighter and more practical to boot.

There are caveats to simply ditching a DSLR for a pricey point-and-shoot. The smaller cameras aren’t nearly as flexible as DSLRs, which have bodies designed for quickly switching shooting functions. Maybe more importantly, DSLRs have interchangeable lenses. These allow you to tailor your setup for exactly what you need. On the street, I might use a fast, 50mm prime whereas for shooting sports you might want a very long 300mm telephoto lens. A universally versatile lens is never as good as pinpointing exactly the right one for the job.

Let’s be real though. Are the bulk of people toting around budget DSLRs really taking advantage of the sophisticated on body shooting controls, or are they simply shooting automatic? What’s the realistic likelihood that the average shooter is swapping lenses in the middle of a dinner party, while they juggle their baby and a bottle in the other arm? And even if they wanted to swap lenses, buying a robust collection is expensive, which is antithetical to the why you would own a budget camera in the first place. On the same point, carrying around lots of lenses is also antithetical to the convenience most people crave.

Yes, these new point-and-shoot cameras aren’t cheap, all costing more than $700. These days you can get a budget DSLR or mirrorless camera with a stock kit lens for that much money, but, again, using only a kit lens largely defeats the purpose of a DSLR. A DSLR will cost you more money, really, than a well considered point-and-shoot, even if these happen to be pricey.

If you’re going to spend the money on a better photographic experience, you shouldn’t be afraid to spend it on the smaller shooter any more. In fact, unless you know for a fact that you need the DSLR, the resurrected point-and-shoot is the way to go.

Picture: Michael Hession