In 1948, the US Supreme Court ended the stranglehold Hollywood studios and distributors had on the US movie market. Declaring the big eight a monopoly and ordering them to divest of their ownership of movie theatres and cease other non-competitive practices, with US v Paramount Pictures, et al, the Court opened the movie industry to independent producers and theatres, and indelibly changed the way we see films (and the films we see).

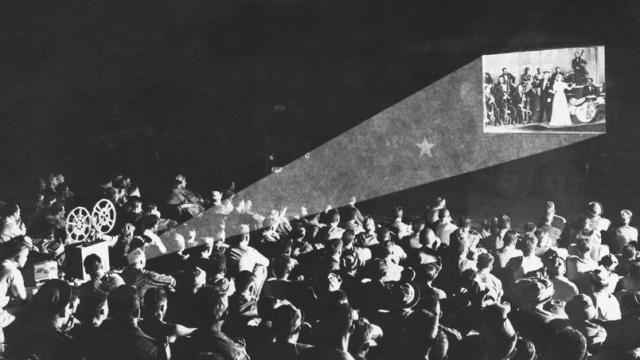

Prior to the government’s efforts to break their trust, a handful of Hollywood studios and distributors controlled nearly all of the movie theatres in the United States, either through direct or indirect ownership, or by the system of “block booking”. With this latter, the big boys insisted that independent theatres contract to run a “block” of films (some set number). Between controlling the distribution and exhibition, and its strong-arm negotiating, these few companies decided not only where and when any movie would be shown, but set admission prices, as well.

Clearly anti-competitive, beginning in 1928 Uncle Sam sought to limit the studios’ power. Identified by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) as having a monopoly over 98 per cent of domestic movie distribution, the Justice Department brought suit in 1929 against Paramount-Famous-Lasky Corporation, First National Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Universal, United Artists, Fox, Pathé Exchange, FBO Pictures, Vitagraph and Educational Film Exchanges (together the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America or MPPDA). Declared a trust in the lower courts, the Supreme Court affirmed the decision on November 25, 1930.

But, since the country was in the mire of the Great Depression, that decision was never enforced, and, rather, in 1933, under the protection of the National Industrial Recovery Act, the studios and the government agreed that the former could continue with business as usual. That is, they continued to own and control movie distribution (and block booking continued, as well).

Nonetheless, as the economy improved, the government decided to limit the big studios’ grip on distribution, and in July 1938, filed another suit, this time against seven studios (Paramount, Loew’s, RKO, Warner Bros, 20th Century Fox, Columbia and Universal) and one major distributor (United Artists). The trial was halted only two weeks after it began, and on November 20, 1940, the parties reached a compromise that allowed the studios to keep ownership of theatres, but inhibited block booking.

This angered independent movie producers, including Charlie Chaplin, Samuel Goldwyn, Mary Pickford, Orson Welles, David O. Selznick and Walt Disney, and together, they formed the Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers (SIMPP) to fight the consent decree. Effective, eventually the antitrust suit returned to federal court, and on December 31, 1946, the district court of New York found the defendants in violation of anti-trust laws. It then ordered that bidding had to be competitive and movies were to be licensed individually, as well as prohibited admission price fixing, block-licensing of copywritten movies, and joint ownership of theatres by distributors and exhibitors, among other things.

The parties returned to the Supreme Court, and on May 3, 1948, it entered its decision. The high court agreed with the district court on most points, including affirming the prohibition against price-fixing, joint ownership, major franchises and block licensing; however, the court reversed and remanded on the issue of competitive bidding, noting:

The system would be apt to require as close a supervision as a continuous receivership . . . . The judiciary is unsuited to affairs of business management and control through the power of contempt is crude and clumsy.[1]

This Supreme Court decision still controls movie distribution and exhibition in the US, and today, studios split gross profits with theatres. But how they do it is pretty interesting.

During the first few weeks of a movie’s run, the studio receives the bulk of gross ticket sales. While the details vary based on deals between the theatres and the distributors, it’s quite common for the theatre to fork over 90 per cent-95 per cent of the revenue from the film on week one, perhaps 80 per cent on week two, etc. By the end of the movie’s run, when the fewest people are going to see a film, the theatre is taking in the lion’s share of the gross. When averaging the whole run, the theatre might only get 20 per cent to 30 per cent of the gross ticket sales, with these numbers varying a bit based on a variety of factors.

As one commentator has noted, this system provides a strong incentive for the studios to make “movies with built-in demand — in the form of a superhero in the lead or a plot drawn from a hit book — and the potential to open with a bang.”

Over time, this has developed such that it’s not uncommon today for theatres to take a loss for a given movie based on ticket sales alone, particularly movies from major studios. There’s really little the theatres can do about this, however, as they have extremely limited leverage in negotiations (particularly for small theatre chains). They can’t make the movies themselves, and certainly can’t turn away major blockbusters, lest people stop going to their theatre(s). In addition, if a given small theatre chain is dealing with a major movie studio, the studio may also say something like, “Well, if you don’t put this movie on 1/4 of your screens for this amount of time and give us X% of the gross, you’ll not be seeing any more Warner Bros. films offered to your theatres.” Major theatre chains have a little more leverage in these negotiations, particularly when dealing with smaller studios, but still not that much in general.

What this all means is that the theatre must find other ways to make money outside of ticket sales. The solution is to charge ridiculous prices for concessions, which nonetheless is necessary for them to stay in business at all, at least given the way things are done today. (The concession hike began in earnest around the 1970s.) For reference, even with the exorbitantly high prices on food items, only about 4 per cent of a theatre’s gross revenue in a given year is profit, despite typically around an 85 per cent profit margin on concession sales themselves, according to Australian market research company IBISWorld.

So, as 55 year veteran of the movie theatre business Jack Oberleitner observed, theatres have “left the movie business and [are] now in the popcorn business.”

On the other side, big movies cost pretty amazing sums to produce, and when they flop, that means huge losses for movie studios, despite the favourable terms they get with theatres. Since many feel this is a direct consequence of the prohibition of studio ownership of theatres, they are calling for a change in the law. One of the many arguments they make is claiming ending the prohibition would have the benefit of allowing studios to target releases geographically to better place movies in more favourable markets, and broaden the types of movies they make. As an example, they point to Magic Mike which “hugely overperformed” in St Louis, Nashville and Kansas City, but had disappointing sales in New York and LA. If the studios owned the theatres, they would have shortened Magic Mike’s runs on the coast, and perhaps shown it more in the Midwest; thereby, suffering fewer losses, earning greater profit, and giving people more of what they actually want.

Another potential benefit of studio ownership of movie theatres is that it would shorten the time it takes a stale film to move from theatres to home release. As one industry insider noted: “If 92 per cent of the gross of a movie comes in the first four weeks, wouldn’t it make sense for [a studio] to put out a movie and say, after four weeks, ‘We’re moving this to DVD?’”

Beyond that, studios would have some small incentive to lower the price of concessions in order to increase the number of people coming to the theatres, and thus increase ticket sales and hype for their movies. If Disney owned theatres saw higher volumes of ticket sales for their movies, and ticket prices were reasonably close between studios, Disney movies would consistently be topping the box office charts. Under the current system, theatres really have little incentive to focus on overall volume of customers, instead trying to focus on the right customers- ones that not only buy tickets, but also are willing to pay the high prices for concessions.

Of course, with the few potential benefits of allowing studios to own theatres again comes potential drawbacks, many of which were seen before US v Paramount Pictures, et al.

Melissa writes for the mildly popular interesting fact website TodayIFoundOut.com. To subscribe to Today I Found Out’s “Daily Knowledge” newsletter, click here or like them on Facebook here. You can also check ’em out on YouTube here.

This post has been republished with permission from TodayIFoundOut.com.