Here’s a staggering statistic: Kickstarter backers pledge roughly $US1.5 million

every day. Crowdfunding is a big business, despite its image as a folksy, grassroots-style approach to money. It’s so big, in fact, that it’s spawning a cottage industry of professionals who can help you cash in on your idea. For a fee.

Picture: Jim Cooke

Kickstarter turned five this year, while its wilder older brother, Indiegogo, is nearly eight. Dozens of other splinter sites have popped up in their wake, and Kickstarter alone has raised more than $US1.3 billion over its half a decade of existence, distributed to more than 70,000 projects. It’s a boon to startups, artists and activists, and a risk for fools too easily parted with a dollar.

It’s also home to a service industry unto itself — dozens of small companies and experts you can pay to help you crowdfund. There’s TeeLaunch, a company that will help you print and send out all those t-shirts you promised your backers. Or BackerKit, an outfit devoted to helping you deliver your final product on time. But before any of that happens, you have to sell yourself to the world. And for that, there are a growing handful of unusual agencies devoted to helping you pitch.

The crowdsourceress

Alex Daly didn’t set out to run other peoples’ Kickstarter campaigns.

She’s a filmmaker who funded a documentary on the site and was so successful, other people started asking her for her natural expertise. Over the course of the last two years, she’s run dozens of successful campaigns — in fact, her agency, Vann Alexandra, has a 100 per cent success rate getting projects funded. It has garnered the nickname “the crowdsourceress,” and today, she’s regarded as something of a wunderkind at getting the internet — an elusive bunch — to believe in the ideas of the designers, artists, and filmmakers who hire her.

The Standards Manual, a Vann Alexandra client.

Let’s say you’re trying to crowdfund an idea for a gadget. Daly and her team can manage nearly any aspect of the process, beginning months before the launch of the final campaign. That could include producing a video for you — arguably the most important, emotional part of your pitch — as well as planning which blogs and other media outlets you should reach out to.

If you don’t have a Twitter feed or a Facebook page yet, Daly’s team can set one up for you. If you need coaching to nail the presentation, or copyediting on your description, they can help you with that too. They will even help you hold up your end of the bargain once your project is funded, managing everything from order fulfillment to payment processing.

I first heard of VA when the agency contacted me with a pitch about a Kickstarter campaign by two designers I had written about before. Curious, I asked Daly how the crowdfunding business was treating her small, Brooklyn-based company.

The answer seems to be: Very well. A small sampling of projects from this year include Neil Young’s a campaign for Pono, a music download service that raised more than $US6 million on Kickstarter, as well as a website called Bellingcat for Brown Moses, née Eliot Higgins, the British journalist behind some of the year’s biggest scoops. They have pushed through campaigns for documentary films, independent venues, and notably, helped gin up $180,000 for a dog gaming console.

Pono, a Vann Alexandra client.

Daly now has so many referrals, she can “cherry-pick” the best campaigns. She describes knowing which campaigns have the greatest chance of success as an “intuitive” process, one that relies on a loose equation of funding goal divided by number of engaged fans.

“I’ve learned that having a huge social media following isn’t the answer to a successful campaign,” she says. “It’s targeting the people within that following and figuring out what they’re interested in. How you can get the most amount of people who are not only interested, but who will convert into dollars.” She has a remarkable knack for finding great ideas from filmmakers, artists, and designers — not always the best salespeople — and helping the internet see why they’re so great.

Getting paid to get you paid

About those dollars.

Ostensibly, anyone who’s using Kickstarter to raise money doesn’t have a conventional budget in place to pay for an agency’s services. So how does Vann Alexandra get paid? It depends on the project. In the beginning, it took a commission from each successful campaign. Now, Daly usually asks for a retainer up front, then a commission based on the final goal and other factors, like how much work is required and how much her team will need to work on fulfillment once the project is complete.

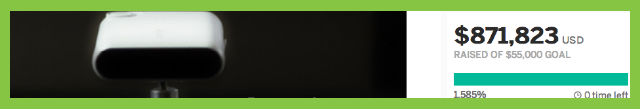

Gramafon, a Vann Alexandra client.

In the end, clients can end up paying up to 20 per cent of the gross funds raised. If you’re talking about a multimillion-dollar campaign, that’s quite a haul.

I asked another crowdfunding services company, Agency 2.0, the same question. Chris Olenik, the co-founder of the agency, was on his way to speak at Indiegogo’s first-ever Hardware Demo Night, a sort of “speed dating” for prospective crowdsourcers interesting in launching campaigns for hardware and tech.

Olenik has been in the business since 2010, when his campaign to fund a documentary about soccer player Jay DeMerit ended up raising $US233,000. He’s since helped several campaigns to raise over $US1 million, many of them for gadgets like a smart pen and Touch Pico, a device that will turn any surface into a touch interface. Agency 2.0 offers many of the same services as Vann Alexandra, and it operates on a purely commission basis. If you don’t make money, neither do the coaches.

TouchPico, an Agency 2.0 client.

Both Vann Alexandra and Agency 2.0 are on the haute couture end of this nascent industry; they are specialists who tailor their fees to you and, in a way, become partners in your campaign by linking their paycheck to your success.

There are cheaper, less personal ways to get crowdfunding advice, too. For a one-time fee of $US349, CrowdFundBuzz will edit your pitch and send it around to prominent bloggers, analysing your analytics and promoting it on social media. A company called Daily Crowdsource will give you an instant consult on your project for $US94 (founder David Bratvold’s fees start at $US20,000). For $US200, this company will write the copy on your landing page. For $US250, they will build you a press kit.

Selling a product that don’t exist… yet

What companies like Vann Alexandra and Agency 2.0 are doing is fairly similar to what a traditional advertising agency does: They take a product and figure out the best way to sell it to people. There’s just one crucial difference in their model: the things they’re helping to push often don’t exist yet.

Equil, an Agency 2.0 client.

That’s both the lure and risk of backing a project on Kickstarter and Indiegogo. And as these platforms boom, a certain percentage of campaigns inevitably won’t follow through with their promises. There was PopSockets, an iPhone case that never arrived. Or Levitatr, a levitating keyboard that will never be produced. Washington State’s attorney general is bringing a consumer protection case against the one company that failed to produce its Kickstarted playing cards.

It’s an increasingly common story as crowdfunding booms. Daly says she hasn’t dealt with it directly with a client yet, but says that it’s getting more and more common. “Before the campaign launches some project creators don’t budget out expenses and are hit hard by shipping, VAT, and production costs,” she said over email. That was the case with one of Agency 2.0’s many technology campaigns: The Kreyos smartwatch (tagline: The ONLY Smartwatch with Voice and Gesture Control).

GoKey, an Agency 2.0 client.

Though plenty of similar campaigns have followed through with their final product, Kreyos was plagued with delays and production issues. When it finally did arrive, backers took to the internet to complain that the smartwatch did just about none of what it claimed to do. Kreyos’ founder, a young entrepreneur named Steve Tan, had promised too much for too little. As Gizmodo’s Eric Limer recently explained, it was a case of an “absurdly low budget goal, unrealistic promises, too-good-to-be-true price tag, all from an untested manufacturer.”

For Agency 2.0, Kreyos was a shock — Olenik had played with an early prototype of the watch — as well as a harbinger of things to come as the nature of crowdfunding changes. “It appears that the exact product delivered was the prototype,” he said over email. “This is very unfortunate to the backers and it is our responsibility to ensure these campaigns never happen again.”

These days, Olenik and his partner vet each client’s project for feasibility and require working prototypes before they agree to take them on. “This is the only way this works,” he says, comparing his system to the ratings that a bank or insurance company might give. “We only represent the strongest of campaigns.”

ChargeAll, an Agency 2.0 client.

It’s certainly not Agency 2.0’s fault for helping a young entrepreneur get noticed. But if Tan’s pitch had looked less slick and professional, and more realistic about the process of developing a device like a smartwatch, would he have raised enough money to try? Should all companies that help crowdfunders have to “vet” their clients’ ideas for feasibility? And if so — assuming they’re even able to vet effectively, given how early-stage most of these are — doesn’t that make them more like partners, rather than service providers?

The core value proposition of Kickstarter and Indiegogo was that they offered a way to bypass the Man and support the Little Guy. That’s no longer exactly the case. Campaigns today are sometimes run by major corporations, and often carefully groomed by smart agencies. The consumer’s role in the bargain, meanwhile, hasn’t changed. Backers are still subject to the risk of an unfulfilled promise or failed product, and few of them possess procedural knowledge about manufacturing and product pipelines. All they have is their emotions and credit cards.

Just like OkCupid, LinkedIn, and even Wikipedia, crowdfunding sites were originally designed to connect people. And just like all three of those sites — which each has its own culture of for-hire experts — Kickstarter and Indiegogo now hosts a vibrant cottage industry of consultants who can help make those connections happen with less friction than ever before. In some cases, incredible projects have become a reality. In others, inherently flawed projects have failed. In the end, these are still the same risky ideas. They’re just harder to tell apart than ever, and come with a prettier bow.