It’s been more than a decade since the Army adopted its first pixelated camo pattern — it was the start of the Iraq War, and the blocky digital pattern seemed to signal a new era of futuristic warfare. One problem: It didn’t work. At all.

The fast realisation that this pattern didn’t work led to something called the Camouflage Improvement Effort — a four-year-long design competition to find something better. In the end, the Army ended up not choosing any of its finalists, instead announcing it would adopt something called Operational Camouflage Pattern, or OCP, last year.

This week, the Army announced that the official replacement pattern would be sold in stores across the country starting in July 1. The Army is finally, officially, putting its decades-long camo nightmare to rest. So why did it take so long? And why did they abandon four years of design work? Read on.

After nearly a decade, multiple false-starts, and many billions of dollars, the Army has finally chosen a new camouflage for its troops. Except it’s not exactly new. It was originally developed back in 2002. And it looks a whole lot like one of the patterns that the Army was in talks to adopt from an independent company.

What happened? Like the patterns at the root of the issue, it’s complicated.

To understand the odd and twisting plot arc of the $US5 Billion Snafu camouflage debacle, you have to look back a full decade. It all started back in 2004, when the Army adopted a new-fangled camo called the Universal Camouflage Pattern, a digital pattern that made quite a splash with its distinctive pixelated look.

Unfortunately, it was also terrible. Really, really terrible. Just totally ineffective and, it turned out, completely untested. In fact, a fatal design flaw is what did it in, as Gizmodo reported this spring. Because the scale of the patterns in the camo were badly chosen, it triggered an optical effect called “isoluminance,” a phenomenon in which the eye interprets many patterns and colours as a single mass. In other words, it was actively making soldiers less safe.

The Army needed a fast fix. Eventually, it adopted a stop-gap pattern for troops in Afghanistan, licensing a pattern called MultiCam from Brooklyn-based security company Crye Precision. It also launched something called The Camouflage Improvement Effort in 2010, a competition to find and test the next Army camo pattern from a group of four final security design teams. The entrants included Crye Precision, the supplier already making camo for troops in Afghanistan.

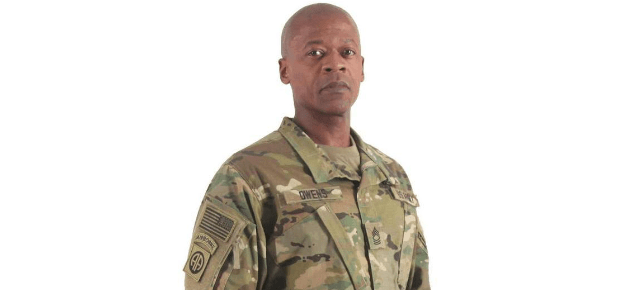

Troops wearing MultiCam on a mission. Image via Crye Precision.

The Army has spent more than four years on the Camouflage Improvement Effort. The four finalists were announced in 2012. But by 2014, the Army was still delaying the winner’s announcement. In January, an Army spokesperson told Gizmodo that “the Army is weighing numerous options and are factoring in recent legislative restrictions,” referring to legislation that would block it from adopting specific patterns for each arm of the military. Rumors ran rampant that MultiCam, or a similar variant, was the pick, since its pattern was already in use.

But as spring lapsed into summer, that announcement never came. Instead, this week the Army released a statement saying it would be adopting a pattern none of its finalists had designed for the Camouflage Improvement Effort. In fact, it would adopt a pattern it designed itself at Natick Research Center, the Army’s Massachusetts lab responsible for designing survival systems for soldiers.

In a terse statement on July 31st, the Army said the pattern would be called Operational Camouflage Pattern. It wouldn’t repeat the mistakes of 2004. And vitally, it would be as fiscally responsible as possible. That’s because this “new” pattern is actually an updated version of a camo developed by Crye under contract for the Army in 2002, according to Military.com’s Matthew Cox.

What the statement didn’t mention was anything about why the Army had abandoned its massive, multi-year Camouflage Improvement Effort, or why talks with Crye about its newer pattern, MultiCam, had broken down. Or more importantly why, in the words of Military.com, the new pattern “mirrored MultiCam.” Here’s a comparison, with MultiCam on the left and the new pattern on the right:

Images: Wikipedia, US Army, via Military Times.

We reached out Crye Precision for a statement, but unsurprisingly didn’t receive a response from the tight-lipped company. Yet we can surmise a pretty good amount about what happened from an extremely rare public statement made by the founder of Crye in March, which slipped under the radar of the non-military media.

According to Crye, the Army had actually chosen Crye’s MultiCam to adopt, but it refused to accept proposals for a fee to licence their pattern. It seems the Army couldn’t afford to use a pattern developed over several years by an independent company, even if testing proved it the most effective pattern available.

That may have been thanks to the new 2014 Defence Authorization Act, which requires the Armed Forces to choose a single pattern to work across all of the services. Congress, imploring that a pattern already in the military’s library be used, effectively stopped the Camouflage Improvement Effort in its tracks.

To make matters worse, the amount it would have cost to adopt MultiCam is surprisingly small. According to Crye, the final proposal would have increased the cost of Army uniforms by just 1 per cent of the current price. “The Army rejected all of Crye’s proposals and did not present any counter proposals,” Crye wrote, “effectively saying that a proven increase in Soldier survivability was not worth a price difference of less than 1%.”

Instead, the Army chose a slightly altered pattern developed by Crye that it had owned since 2002, two years before its camo debacle even began. In other words, the past 12 years, billions of dollars, and incredible resource investment could have been easily avoided.

The government is cutting defence spending drastically, and the Army is bearing the brunt of the cuts. It even plans to dye some equipment and vests printed with the useless digital camo pattern that began this debacle brown so they can still be used. But it’s hard not to wonder if the Army’s abrupt adoption its own version of an older camo pattern — rather than MultiCam, which was created to improve upon that very pattern — isn’t just a repeat of the disastrous 2004 decision that set the events of the last decade into motion.

Hopefully it’s not. Hopefully, the new pattern is just as effective, even if it means Crye was thrown under the bus. Because in the end, whether or not it’s a rip off or a waste of money, the lives of hundreds of thousands of people depend on it.

UPDATE: An unnamed army official had the following to add to the story, adding that it “missed some points about the camo effort:”

The biggest one is the claim (oft-repeated) that it was a $US5 billion waste. That’s not true because people conflate the purchase of uniforms and equipment with the camouflage effort. They are different. For instance, the vast majority of that amount refers to the purchase of uniforms which were used, worn out and discarded during the time period which is referred to. So that was not “wasted” money. People got their use out of that gear. There WAS money spent on development of camouflage, and that, of course, is a sunk cost. But that is a matter of several million dollars, not $US100 million, and certainly not $US5 billion.

This is not a defence of UCP, which, although it performs pretty well under night conditions, will not be missed by the most Soldiers.