Josephine Daskam Bacon was an author known for her adventure serials that featured female protagonists. But in 1929, she took a break from her regular fiction writing and slipped on her futurist goggles for an article in Century magazine titled “In Nineteen Seventy-Nine”.20 Bacon imagined just how much progress women will have made fifty years hence — and whether her granddaughter would be able to “have it all” as some people here in the future might say.

In the article, Bacon looks back at the generations of women that had come before her and pokes a bit of fun at the Hartford Woman’s Friday Club, who in 1878 decided that “electricity was too uncertain and dangerous to be put to any practical use.”

These women, Bacon explains, can be forgiven for not appreciating some aspects of the technological revolution that was to come.

A generation to which telephones and bathtubs were luxuries, which had never ridden in an automobile, to say nothing of an aeroplane, nor seen a moving picture, nor heard a radio concert, must be pardoned for its incredulity.

For many women at the turn of the 20th century, technology was interwoven into what it meant to be a feminist. Many utilized technology as a force for their cause — whether it was spreading their message through radio, driving cars despite ridicule from men, or even imagining the meal-in-a-pill as a great liberator from the drudgery of the kitchen.

But many younger women of the era were frustrated and shunned by their mothers and grandmothers who didn’t understand how certain technologies could play any role in the life of the average woman.

My grandmother, if any one had told her that her granddaughter could take her choice of going below in a submarine or sailing above in an aeroplane, would have answered, “Don’t be foolish!” She simply couldn’t believe it. But she knew whether I was going down, down to Hell or up, up to Heaven, and when and how and why. Oh, yes, she knew all about that! She could believe anything in that line, with perfect ease.

Bacon insisted that her grandchildren would be different, and that no one will bat an eye when a young woman of 1979 “expects to visit Mars or Venus.” The women who grew up in the 1920s wouldn’t be surprised at all, because they’d already seen such radical change.

Because I’ve seen the automobile and the X-ray and the aeroplane and the radio and the television born and developed and commercialized. You can’t stagger me.

Every generation seems to believe that they’re special and that technology is being developed at an increasingly rapid pace. And for Bacon, writing in 1929, it’s easy to see why she felt the same way. Her mother and grandmother had little to point to in the way of technological progress, she argued. And thus, social progress was even harder for them to imagine.

This explains why prophecy in 1929 is bound to be different from prophecy in 1879. We don’t look into our hearts or read old books or go into trances, to prophesy, nowadays. We observe what is being done, and push the idea further. In the case of science, this is a little dull: you simply say, “More electricity! More radium! More atoms!” You can’t go wrong.

Bacon had the proper scepticism that technology alone wasn’t going to fix everyone’s problems. But she understood that this collective ability to see into the future influenced the real world.

Once humanity pushed past the inability to properly envision change — technological or otherwise — then women would begin to see real social advancements, Bacon insisted. The woman of the year 1979 would have many options, especially when it came to things like working outside of the home.

And so I feel safe in foreseeing, before the next fifty years, an adjustment between the woman, her man, her child and her job. She may do this by marrying early, rearing her children, and tackling her job later in life, as many women have done. She may do it by combining job and children early in life, helped by kitchenettes, day nurseries, shorter working hours and higher pay, as many are doing to-day. She may have all job and no children, as she has surely a right to do, if she prefers this; or no job and all children, which some women will always prefer.

So how will the working woman of 1979 get to her job? By flying machine, of course.

That she will fly to her job in a plane we cannot well doubt, but we shall be foolish if we assume that she will therefore wear an aviator’s costume, because the motor veils and goggles and enveloping coats of my girlhood have long lain on the dust heap, and I have seen women in evening dresses and women in bathing suits driving cars with equal ease.

Motor veils and goggles to drive a car? Before the days of windshields these were indeed necessary, as you can see from the 1910 photo below.

But Bacon accurately predicted that just because aeroplanes will be common, doesn’t mean ground transportation will go away entirely:

Nor do I believe that the streets will be grass-grown, as some one suggested to me as the one certain prophecy. I remember too well that increased service on the elevated roads left the street cars and buses fuller, that subways saw the elevated roads still crowded, that motors, doubled and redoubled again, saw the subway still jammed. No, the most the aeroplanes can do is to ease the traffic a little, and spread the accidents over a wider surface.

Bacon described all kinds of shiny, futuristic things that would come to pass by the year 1979. But she always brought the article back to changes that many male futurist writers of the time were ignoring. Bacon even speculated what women of tomorrow might think of religion.

And her religion? Surely it is safe to assume that she will continue to grow less and less interested in what she may do when this life is ended, and more and more concerned with what she can accomplish while she is living it!

Bacon’s prescience truly shines at the end of the article. She begins to wonder about the life that her granddaughter will have, and what material prosperity will bring. Will she be happy to simply continue to work longer and harder hours, acquiring more and more things?

Yesterday, as soon as everybody had a bath-tub and an automobile and a radio set, he worked a little harder, so that to-day he has six bathtubs and two automobiles — and another radio set! Will my granddaughter think of nothing more original than to carry three times as many jobs as her mother carried?

I cannot believe this. Even now some of us are asking, “after prosperity — what?” Even now we are sadly realising that the good of an automobile depends largely upon where you go in it and what you do after you get there, and that sanitary plumbing may be the means of American life, but can hardly be expected to represent the end of it. If we can see this, we, who still sit in the shadow of that great war which shook so many social foundations and shattered so many naïve ideals surely our grandchildren will see it even clearer and refuse to keep working so that more and more people may jump prosperously from a bath-tub to an automobile — and then jump back again!

Sadly, we’re still asking ourselves the same questions about just what we’re working toward here almost a century later. The leisure society that we were promised never arrived. In fact, we’re working as hard as ever to maintain a mainstream American standard of living comparable to postwar levels.

“After prosperity, what?” may have been the question of a more optimistic age. But most Americans are still working for that prosperity part. Even for Bacon — who was writing in early 1929, just before the stock market crash of October — she still had the Great Depression and World War II yet to come.

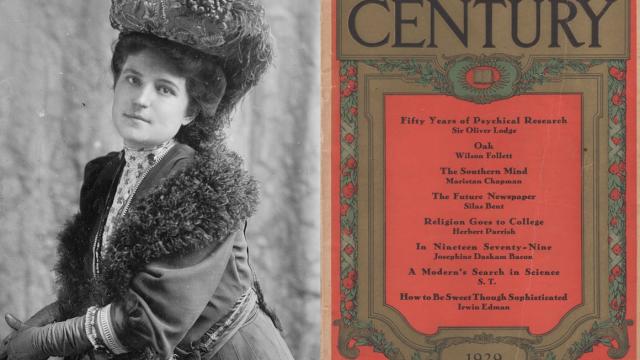

Pictures: Josephine Daskam Bacon in an undated photo from the Library of Congress; Scanned cover of the January 1929 issue of Century magazine; Woman and her dog on the seat of an automobile circa 1910 via Library of Congress