There is only one true sexbot that you can go out and buy today. Her name is Roxxxy, and she is a ‘robot companion’ intended to look human, or something very close. She’s 5’7″ and slender. She’s got a wide range of hair and eye colours. And depending on the model you choose, she can ‘hear’ you, ‘talk’ to you, and ‘feel’ you.

Roxxxy is decidedly a robot. Unlike some of the gynoids and actroids, Roxxxy does not quite produce the ‘uncanny valley’ effect, where a robot is so close to being human but different enough to create a feeling of revulsion. Roxxxy is mannequin-like, and comes with her very own personality. While she likes the same things as her owner, she has moods too, and can sometimes get sleepy. She can also take on additional preprogrammed characteristics, such as ‘Mature Martha’, ‘Young Yoko’ or ‘Frigid Farrah’. Young Yoko is aged just over 18, but she’s inexperienced and wants to learn, whereas Mature Martha can show her owner the ropes. Wild Wendy is up for anything, while Frigid Farrah needs a lot of coaxing.

The personalities offered by Roxxxy are crude types, but they are instructive, insofar as they tell us what sexbots are likely to proliferate, especially as the technology to customise them becomes more sophisticated. In a few decades time, sexbots might be as commonplace as vibrators. We’d do well to start thinking about what they might mean for human culture.

In 1902, Hamilton Beach Brands filed a patent that enabled them to sell vibrators directly to consumers, rather than only as a medical device. With this patent, the vibrator became the fifth electrified domestic appliance, beaten only by the sewing machine, the fan, the tea kettle, and the toaster. The vibrator was still advertised as a health and medical device but, in the 1920s, the sexual use of vibrators became more explicit through pornography.

There are toys for men too, although unlike toys for women, which straddle solo and partner play, heterosexual men’s toys are largely masturbatory devices. There is the Fleshlight, a sleeve of ‘flesh-like’ material housed inside a fake plastic flashlight. Remove the cap and the top of the material is shaped like a vagina, an anus, or a mouth, ready to be lubricated and penetrated. Or there’s the Soloflesh Personal Satisfaction Device, a sex toy shaped like a floating pair of buttocks with a vagina; just fill it with warm water and it’s ready for sex.

From there, things shade into something more sexbot-like, such as FriXion, which uses sensors and robotic accessories to assist in remote-controlled sex. The robot appendages use haptic technology, which allows users to grip or penetrate their partners across long distances, with touch not words.

Some of the newest and most intriguing sex technology veers away from traditional sex toys in a particular way: it is based around sharing and connecting. By and large, teledildonics and sexbots are made for and marketed either to couples or to men. Almost none are marketed directly to women, which means that the way we create and view sex technology is being filtered through a very particular perspective: a heterosexual male one.

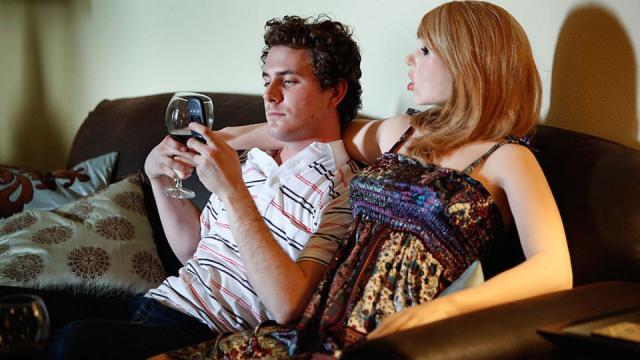

Much of the discourse around emerging sex tech is male-focused. Roxxxy’s roots were in the recreation of a friend lost in the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, but she has grown into a sexbot who exists to match and please her owner. Some find this servitude unobjectionable, because AI is still very much not human. But what if we think about sex technology and sexbots as part of a shared experience? What if we work to program these sexbots so that they are not simply objects to control and swap like livestock, but beings with whom to share intimacy?

Perhaps the best-known work on intimate relationships with robots is by the British author, chessmaster, and CEO of Intelligent Toys Ltd, David Levy. Levy argues that as long as sexbots are artefacts, without ‘artificial consciousness’, there are no ethical implications in having sex with them or using them for prostitution. However, should sexbots attain artificial consciousness, Levy argues there may be both legal and ethical implications not only for humans but for the robots themselves.

If women are the model on which most sexbots are based, we run the risk of recreating essentialised gender roles, especially around sex. And that would be too bad, because sex technology has the potential to alleviate longstanding human problems, for both men and women. Sex tech can help us take on sexual dysfunction and profound loneliness, but if we simply create a new variety of second-class citizen, a sexual creature to be owned, we risk alienating ourselves from each other all over again.

This article has been excerpted with permission from Aeon Magazine. To read in its entirety, head here.

Aeon is a new digital magazine of ideas and culture, publishing an original essay every weekday. It sets out to invigorate conversations about worldviews, commissioning fine writers in a range of genres, including memoir, science and social reportage.