Tattoo is among humanity’s earliest and most ubiquitous art forms. Cultures from every habitable continent have embedded permanent dyes in their bodies for more than 5000 years — as mystical wards, status symbols, rites of passage, or simply as personal decoration. That tradition continues today, just with a much smaller chance of infection.

The Ancient Origins of Body Modification

Otzi’s tattoos – image: The South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology

Tattooing has been since at least the Stone Age. Otzi, the famous neolithic Ice Man, sported a series of 57 carbon-based tattoos (thought to be healing wards akin to acupuncture). As Joann Fletcher, research fellow in the department of archaeology at the University of York in Britain, explained to Smithsonian Magazine:

Following discussions with my colleague Professor Don Brothwell of the University of York, one of the specialists who examined him, the distribution of the tattooed dots and small crosses on his lower spine and right knee and ankle joints correspond to areas of strain-induced degeneration, with the suggestion that they may have been applied to alleviate joint pain and were therefore essentially therapeutic. This would also explain their somewhat ‘random’ distribution in areas of the body which would not have been that easy to display had they been applied as a form of status marker.

So too did numerous pre-Columbian cultures of Peru and Chile. For example, the enigmatic Moche civilisation that ruled over large swaths of the Andes around 500 BC and built the Moche Sun Pyramid — the largest adobe pyramid in the Americas — used tattooing to signify their leadership. Archaeologists had long assumed that the society was strictly patriarchal, until the discovery of an exceptionally well-preserved, heavily tattooed female mummy in 2006 indicated a more gender-equal community.

Bearing both religious figures and magical wards of spiders and snakes tattooed on her arms, legs, and feet, the 25-year-old woman is the first female Moche leader ever discovered. The fact that she was found buried with ceremonial war clubs, 23 spear throwers, and the corpse of a teenager (likely strangled as sacrifice during the burial), all support the notion that she was among the highest ranking members of society.

Tattooing was also routine among Native American tribes, often as religious insignia or as medals of victory in war. Just as later aviationists would stamp the number of enemies they’d shot down on their plane’s fuselages, young men in these societies would use their own bodies as scoreboards, notching their skin and rubbing in coal or okra for every head they’d taken in a skirmish or raid.

Image: George H. Wilkins – Library and Archives Canada

Not all tribes used tattoo for such macabre means. The Inuit, for example, have been tattooing themselves in the name of beauty and a peaceful afterlife since at least the 13th century. As Cardinal Guzman, author of The History of Tattoo, explains:

Eskimo women wore tattoos that, along with other facial decorations were considered to increase the feminine beauty. Such tattoos signaled a women’s social status, for example, that they were ready to get married and have children. The tattoos were often very extensive and included vertical lines on the chin with more intricate design by the rear parts of the cheek in front of the ears. The markings were made with needle and thread that was covered with soot and then dragged under the skin following a specific pattern. Piercing was also common, jewelry made of bone, shell, metal and beads were crafted into the lower lip.

The tattooist was an older woman, usually a relative, and according to belief only the souls of brave warriors and women with big, beautiful tattoos were granted access to the afterlife. The men often tattooed short lines in the face, and in the Western Arctic regions, the whale hunting men kept records of their success as hunters with the help of these lines.

Similarly, in the the Cree tribe, men would often tattoo their entire bodies while the women would wear ornate designs running from mid-torso to pelvis as protective wards for a safe pregnancy.

And along the Pacific coast, the Maidu tribe used tattoos for fashion alone. As Alfred L. Kroeber has pointed out in the Handbook of the Indians of California (1919):

The Maidu are on the fringe of the tattooing tribes. In the northern valley the women wore three to seven vertical lines on the chin, plus a diagonal line from each mouth corner toward the outer end of the eye. The process was one of fine close cuts with an obsidian splinter, as among the Shasta, with wild nutmeg charcoal rubbed in. For men there existed no universal fashion: the commonest mark was a narrow stripe upward from the root of the nose. As elsewhere in California, lines and dots were not uncommon on breast, arms, and hands of men and women; but no standardized pattern seems to have evolved except the female face.

A Young Daughter of the Picts, Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, ca. 1585

For pre-Christian Celtic and Germanic peoples, such as the Picts, who first inhabited the British Isles, tattooing was common among both sexes. In fact, the world Britain is derived from Britons or “people of the designs,” as the Picts were described by Julius Caesar himself in Book V of his Gallic Wars. However, whether the inking was religious, decorative, mystical, or a bit of all three remains up for debate.

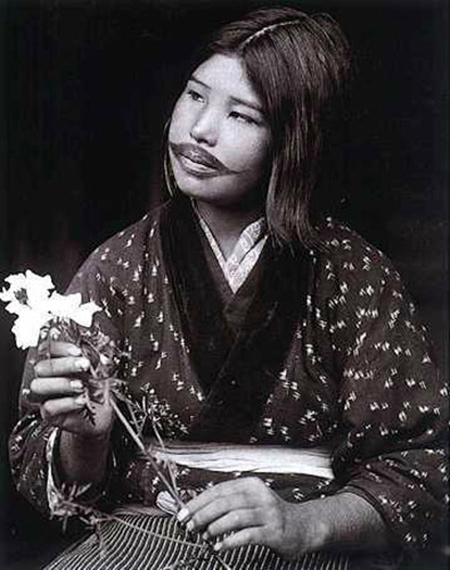

Tattooing was contemporaneously widespread throughout Asia. While the Chinese largely considered tattooing a barbaric practice, convicts and slaves were at times inscribed with marks denoting their status as criminals and property. Tattooing was popular among the indigenous Ainu people of Japan, whose women tattooed their mouths and forearms from a young age using birch bark soot. The Ainu’s mouth designs often resemble mustaches. This dovetails with another Ainu tradition wherein all men stop shaving a certain age and sport long full beards.

The tattooing tradition remains strong in Japan with members of the Yakuza, Japan’s organised crime syndicate, often sporting ornate, full-body artwork.

image: Jorge

Additionally, many indigenous tribes throughout Indonesia — such as the Dayak people of Kalimantan in Borneo — practice tattooing. Known as Kalingai or pantang, these designs were inscribed to protect their bearers from danger.

A traditional Dayak tattoo session – image: Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT)

Crude Tools

The very earliest method of tattooing involved cutting or pricking the skin and rubbing ash into the wound (in order to get the dye past the epidermis and into the dermis itself). Early tattoos were applied with what was essentially a long stick with a sharp point embedded in one end, a method that’s been in use since at least 3000 BCE, as discovered by archaeologist W.M.F. Petrie at the site of Abydos, Egypt. The implement he found used a set of wide flattened needles tied together at the end of the stick and created a dotted pattern when used.

In fact, tattooing was very common among women of the Pharoes’ court. As Fletcher told Smithsonian Magazine:

There’s certainly evidence that women had tattoos on their bodies and limbs from figurines c. 4000-3500 B.C. to occasional female figures represented in tomb scenes c. 1200 B.C. and in figurine form c. 1300 B.C., all with tattoos on their thighs. Also small bronze implements identified as tattooing tools were discovered at the town site of Gurob in northern Egypt and dated to c. 1450 B.C. And then, of course, there are the mummies with tattoos, from the three women dated to c. 2000 B.C. to several later examples of female mummies with these forms of permanent marks found in Greco-Roman burials at Akhmim.

The Tour Egypt website provides additional examples:

Among the best-preserved mummies is that of a woman from Thebes from Dynasty XI (2160-1994 BCE), whose tomb identifies her as Amunet, Priestess of Hathor. Sometimes described as a concubine of Mentuhotep II, tattoo patterns remain clearly visible on her flesh. No amulet designs for Amunet. Instead, she bore parallel lines on her arms and thighs and an elliptical pattern below the navel in the pelvic region…Several other female mummies from this period also clearly show similar tattoos as well as ornamental scarring (cicatrisation, still popular in parts of Africa) across the lower abdomen.

The Egyptian procedure, which involved runic designs, apparently changed very little over the course of 4000 years. Witnessed by 19th century traveller and writer William Lane, “the operation is performed with several needles (generally seven) tied together: with these the skin is pricked in a desired pattern: some smoke black (of wood or oil), mixed with milk from the breast of a woman, is then rubbed in…. It is generally performed at the age of about 5 or 6 years, and by gipsy-women.”

The Maori tribe of New Zealand and Polynesian cultures are perhaps the most well known examples of early tribal tattooing practices, which have been a vital part of their respective cultures for more than 2000 years.

image: unnamed Maori Chief – Sydney Parkinson, 1769

As with other generation-spanning cultural tattoos, the Polynesian tradition has changed very little over the past two millenia. The traditional tool, known as an au, is constructed from sharpened boar tusks fastened with a portion of turtle shell and attached to a wooden handle. After dipping the tusks in dye, the tattoo artist would whack the turtule shell backing with a mallet, driving the tusks into the person’s flesh. Given that men, especially high ranking members of the society, would be tattooed from mid-torso to knee, each session would last from sun up to sun down and take up to a year to full heal, requiring the skin to be repeatedly washed in salt water to remove impurities. The process was excruciating and often rife with potentially lethal infections.

Western Spread

The word tattoo is derived from the Tahitian “tatau”, and was introduced into the English language by Captain James Cook after returning from his voyages in the South Pacific in the mid-18th century. In his ship’s log book, Cook explains:

Both sexes paint their Bodys [sic], Tattow, as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the Colour of Black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible. This method of Tattowing I shall now describe…As this is a painful operation, especially the Tattowing of their Buttocks, it is performed but once in their Lifetimes.

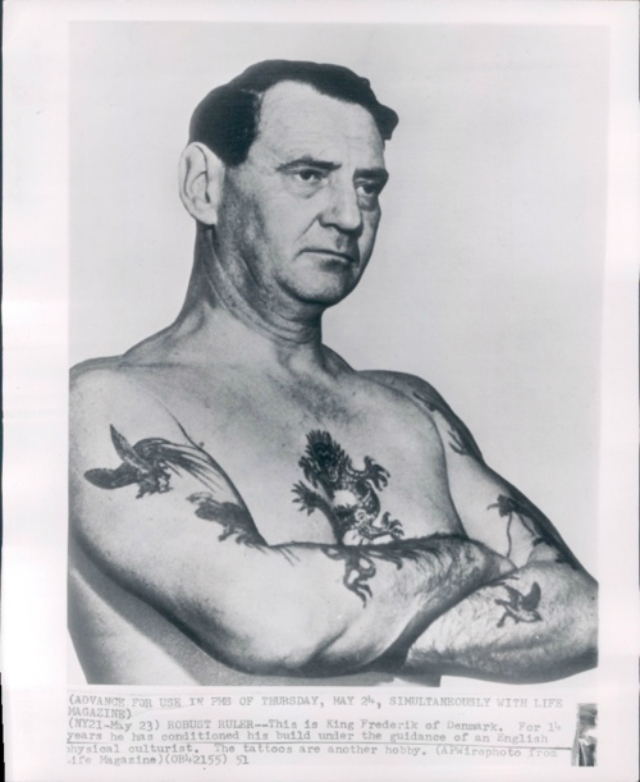

Not only did Cook’s expedition witness these procedures, many of his men — including his aristocratic Science Officer and Expedition Botanist, Sir Joseph Banks — returned to England with the marks. Thus began the popular association of sailors and tattoos (think Popeye) and helped further spread the practice around the globe. In fact, by the 19th century, many of Europe’s aristocracy sported tats, including English Kings Edward VII and George V, King Frederick IX of Denmark, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and even Tsar Nicholas II of Russia.

King Frederick IX of Denmark, 1921 – Time Magazine

The practice became popular in America around the end of the 18th century when American sailors would routinely be impressed into service aboard British ships. As Catherine McNeur of Common Place illustrates:

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, tattoos were as much about self-expression as they were about having a unique way to identify a sailor’s body should he be lost at sea or impressed by the British navy. The best source for early American tattoos is the protection papers issued following a 1796 congressional act to safeguard American seamen from impressment. These proto-passports catalogued tattoos alongside birthmarks, scars, race, and height.

Using simple techniques and tools, tattoo artists in the early republic typically worked on board ships using anything available as pigments, even gunpowder and urine. Men marked their arms and hands with initials of themselves and loved ones, significant dates, symbols of the seafaring life, liberty poles, crucifixes, and other symbols.”

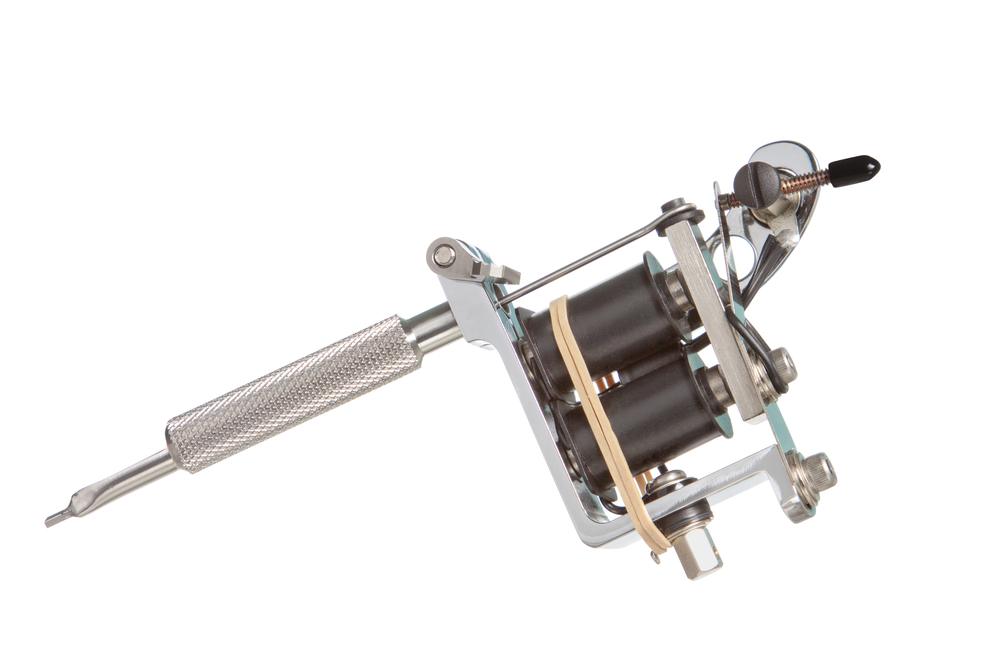

While people can — and still routinely do — get tattooed using the traditional Polynesian needle-stick method, the tribal arm band that your barrister is rocking was most likely applied with the modern method: a needle gun. Comprising a sterilized needle driven by an electric motor, the gun injects dye about a millimetre under the skin at a rate of 50 to 3,000 pricks per minute and is controlled via a sewing machine-style foot pedal.

Rise of Modern Tattoo Machines

A rotary tattoo machine – image: Access Tattoo

The modern tattoo gun traces its roots back to Samuel O’Reilly’s 1891 invention of the rotary tattoo machine, the world’s first such patented device. Based on an earlier patent by Thomas Edison designed to make copies of office documents by punching through the original and depositing ink in a second leaf of paper underneath. This device employed an electric motor to drive a rotating crankshaft which lifted and lowered the needle.

A coil tattoo gun – image: dondesigns

Later improvements on this initial design integrated a fitted ramp that increased the drive’s efficiency. Known as coil (or hybrid rotary) tattoo machines, these are the most commonly used type of tattoo gun. Unlike their rotary forerunners, which used a physical mechanism to drive the needle, coil guns use an electromagnetic circuit to do so, generally causing less damage to the skin.

A pneumatic tattoo machine

The latest revolution to tattoo technology came in 2000 when Tattoo Carson Hill debuted the world’s first pneumatic tattoo machine. Unlike electrical guns, a pneumatic tattoo machine is gas driven and, more importantly, can be sterilized sterilized in an autoclave. This drastically reduces the rate of post-inking infection. Going beyond that, the Neuma company introduced a hybrid pneumatic-electric machine in 2009 that actively released an antimicrobial agent whenever the needle touches liquid. This all but eliminates the chances of the machine picking up a blood-borne pathogen which can be spread to the next customer.

The Modern Tattoo Renaissance

Tattoo artist Ron Ackers at work in Bristol, Great Britain c. 1950’s – image: Vintage Gal

These days, it’s not just sailors and ruffians that get inked. Everyone from soccer mums to CEOs, grandfathers to Miss America contestants, all sport tattoos. Since the 1950s, in fact, there has been a global renaissance in tattooing, especially in Western cultures. Led by seminal tattoo artists like Lyle Tuttle (who did the famous heart tattoo on Janis Joplin’s left breast), Cliff Raven, Don Nolan, Zeke Owens, Spider Webb, and Don Ed Hardy. The revitalization of tattooing has been led in part by continual refinements to the machines’ technology as well as rapidly changing social mores and a new generation of people attempting to reconnect with their cultural heritages through the practice.

Masters Series: Paul Timman, Hollywood Tattoo Artist

Hype around tattoo culture reached fever pitch in the early naughts, with shows like Inked, Miami Ink, and LA Ink bringing the art of tattoo into the realm of pop culture. Today, tattoos are considered high art with numerous contemporary art exhibitions and visual art institutions featuring tattoos as gallery art. And there are all kinds of technological advances just around the bend. [Motherboard – Extreme Tech – Tattoo Archive – Tattooing Today – PBS – Smithsonian Magazine – Wiki 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 – Red Orbit – The History of Tattoo]

Top picture: A portrait of Tukukino – Gottfried Lindauer