For the last four years, the Dredge Research Collaborative has been looking at dredging and erosion control as a form of often unacknowledged landscape architecture. Part of their work is a series of festivals they’re calling DredgeFest that celebrate and examine the role that dredging plays in landscaping. Their next event is in Louisiana. Gizmodo asked them to explain why.

Rivers move. They move water, obviously. They move earth, too. Vast amounts of it. The Mississippi and its tributaries pick up about 200 million tons of sediment from the continental US and dump it into the Gulf of Mexico, every year. All that silt and sand and mud and muck gets sprayed out at the river’s mouth. Historically, a lot of it got washed away by the ocean, but not all of it, not fast enough. Over the last 4,000 years, that steady accumulation — which was once at least twice its current volume — formed the southern half of what is now Louisiana. Geographer Richard Campanella has called the Mississippi River “the land-making machine.” It makes land. At least, it used to.

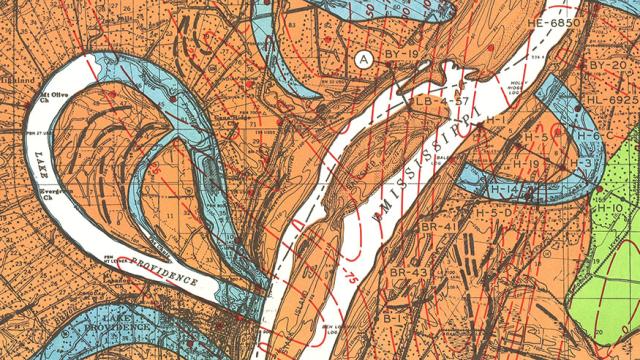

Map courtesy of the US Army Corps of Engineers

Rivers move themselves. Given time, their bends grow wider and wider until they begin to cross themselves, jumping into new channels. For a particularly meandering river like the Mississippi, this happens relatively often. Too often for human tastes. When you’ve built your industry on the banks of a river to float your products to market, it won’t do to have your highway dry up. When you’ve spent years building up a farm, it’s not acceptable for it to become a riverbed.

Rivers have a rhythm. The rhythm is seasonal, dependent on winter snow and spring rains and spring snowmelt. The rhythm is erratic, like the weather that it depends on; one year, the river may swell but never top its banks. The next, the river may swell so greatly that it overtops its natural banks, filling the floodplain beyond. And, some years, the river may swell so greatly that it not only overtops its natural banks, but also the piles of dirt — the levees — that humans mound along it to protect their settlements, their fields, and their homes. (Sometimes, when it does this, it does so explosively. This is called a crevasse.)

And so Americans, at once dependent on the Mississippi for their livelihoods and fearful of its erratic capacity to destroy, have attempted to freeze the river in time and place. Not the water, of course; that must be allowed to flow. But the course of the water has been set by policy and by infrastructure. Given that the flowing water is the reason for the changes of course, allowing one while preventing the other demands a great deal of policy and infrastructure indeed.

Image courtesy of the US Army Corps of Engineers

It can be difficult to see it up close, but take in the grand network of dams, channels, levees, spillways, banks, and marshlands, and it becomes clear that the Mississippi is one of the grandest projects of landscape architecture on the planet. It is a Sisyphean project. There is no moment when the landscaping of the Mississippi will be done. Instead it is a constant process of maintenance and control, which threatens to spiral out of control as a complex system of feedback loops absorbs the twin shocks of intensifying human activity and an increasingly wild climate.

In fact, left to its own devices, the Mississippi wouldn’t be the Mississippi anymore. The reason is a mixture of natural erosion — rivers move — and human intervention.

Travel upriver from New Orleans, and you can catch a glimpse. There’s a point where the corner of the state of Mississippi pokes into Louisiana; go a little further and you’ll find Old River Control. A thousand years ago, another river called the Red River ran parallel to the Mississippi, both rivers moving water from the middle of the continent to the Gulf of Mexico. But, about five hundred years ago, the Mississippi meandered far enough west that it connected with the Red. The bottom part of the Red became what is now known as the Atchafalaya. The meander, called Turnbull’s Bend, was a long, languid loop. You could travel 20 miles downriver and end up only one mile from where you started.

In 1831, motivated by the accelerating importance of the Mississippi as an industrial highway, river engineer Captain Henry M. Shreve cut a canal to straighten the route. This sped up travel time, but it also began to cause serious problems. The Atchafalaya, which takes a more direct route to the Gulf, started scouring a deeper and deeper channel, in the process siphoning more and more of the Mississippi’s flow. (Though accelerated by Shreve’s canal, this switch in direction is, in geologic time, ordinary and expected. The Mississippi has taken a number of different routes to the Gulf in recent millennia, each time building a new “lobe” of the Mississippi River Delta. The river always finds the shortest and steepest path to the Gulf.) In the 1950s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers determined that unless something was done, the Mississippi would divert course entirely by the 1990s, sending a mighty channel of water pouring down the Atchafalaya and marooning New Orleans along a shriveled river.

Image courtesy of the US Army Corps of Engineers

The Corps’ response was Old River Control. Built in 1964, its job is to stop the Mississippi from changing course, freezing for perpetuity the 70/30 split in waterflow of the mid-twentieth century. It nearly failed in 1973. It’s been reinforced and expanded twice since then. If it ever does fail, it will be one of the greatest infranatural catastrophes in American history, both for the immediate flooding in the Atchafalaya Basin and the long-term choking of New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and the industrial corridor along River Road between the two cities.

Like all large and complex infrastructural projects, the attempt to control the Mississippi has had enormous unintended consequences, most notably that the land-making machine is now thwarted. The same riverine rhythm that flood control infrastructures have understandably sought to tame was essential to the land-making power of the river, as floodwaters carried sediment from distant upstream sources into floodplains and marshes in such massive volumes as to cause land to rise out of the Gulf. Constrained by levees reinforced with articulated concrete mattresses, locked into a single course at Old River Control, and starved of sediment by massive upstream dams, the Mississippi no longer floods, so there is no source of sedimentary accumulation. Erosion gains the upper hand.

Image courtesy of the USGS

As a consequence, south Louisiana is disappearing — terrifyingly fast. Sea-level rise, salt water intrusion, and canal excavation for industrial purposes have all combined with the constrainment of the river via flood control infrastructures to radically alter the balance between deposition, subsidence, and erosion. Instead of growing, the delta is now shrinking. Louisiana has lost over 1700 square miles of land (an area greater than the state of Rhode Island) since 1930. Without a change in course, it is anticipated to double that loss in the next 50 years. By 2100, subsidence, erosion, and sea level rise are projected to combine to leave New Orleans little more than an island fortress, effectively isolated in the rising Gulf of Mexico.

Moreover, even where the land itself may not be entirely submerged, the loss of barrier islands and coastal marshes exposes human settlements ever more precariously to the vicious effects of hurricanes and tropical storms, including the destructive waves known as storm surge.

This situation is entirely untenable. You thought Katrina was a terrible disaster? (It was.) Imagine what happens to New Orleans when a Category 6 hurricane hits in 2086, when even the highest ground in the French Quarter and the Garden District is barely above sea level and well below the ever-thickening barriers the Army Corps will throw up to protect America’s newest island.

Image courtesy of CPRA

In response to this apocalyptic but plausible threat, Louisiana is engaging in the world’s first large-scale experiment in restoration sedimentology. With the aid of components of the federal government like the Army Corps of Engineers and a bounty of funds earmarked for coastal restoration and protection as a result of payments owed by BP for the damages wrought by the 2010 Deep Horizon oil disaster, Louisiana has accelerated its nascent crash-program in experimental land-making machines, rapidly prototyping a wide array of weird and wonderful techno-infrastructural strategies for building land. This is an effort to cobble together a synthetic analogue to the land-making machine that the Mississippi once was. If you want to understand the future of coastlines and deltas in a world of rising seas and surging storms, you should pay close attention to what is happening in Louisiana.

Marsh Terracing

Image courtesy of NOAA

Marsh terracing is perhaps most fascinating for what it does not do, which is make any attempt, as the great majority of landscape restoration techniques do, to hide its thoroughly anthropogenic origins. Instead, marsh terracing is boldly and rigorously geometric, imposing precisely engineered patterns composed of chevrons, squares, and perpendicular lines onto the fractal disorder of coastal marshes. These patterns are engineered from raw sources of imported sediment like dredge, often covered in marsh vegetation fastidiously hand-planted on their flanks, and intended to slow, trap, and accrete sediment as it washes out into the Gulf.

Dredge Pipelines

Image courtesy of NOAA

Dredging is typically understood as a linear industrial process: there is sediment in that navigation channel, ships need to pass through, so we suck or scoop the sediment up, transport it somewhere out of the way, and dump it. Dredging is maintenance, and sediment is the problem. But in places like south Louisiana spare sediment is not a nuisance to be disposed of as cheaply as possible, but rather a precious resource which can and should be utilized. The Mississippi needs to be dredged because it is a crucial industrial corridor, but the sediment captured in this process is too valuable to waste. Consequently, dredged sediment is frequently pumped long distances through dredge pipelines, rusting red-brown metal pipes which clang musically from the rhythmic passage of loose rocks, alternately tunnel through levees and pass across open water on pontoon platforms, and discharge into designated target areas with spectacular plumes of loose, watery sediment. This raw land-making material is typically contained by crudely geometric dykes which ghostly outline the intended expanse of new land, producing another distinctive contrast between the emergent form of spilled sediment and the obviously human borders.

Participatory Micro-dredging

Not every act of restoration occurs at the industrial scale of navigational channel dredging. The Audubon Society is experimenting with their own bespoke dredger. The idea is that the much-smaller-than-usual vessel can redistribute muck to create new land that will become habitat without unduly disturbing the environment or its occupants. The Audubon’s dredge takes about 400 hours to fill an acre, all told. With only one, that’s depressingly slow. But this is a prototype of what could be relatively inexpensive, local-scale dredges. It’s easy to imagine a swarm of dredgers, shaping and reshaping the land according to their local needs.

Sediment Diversions

Image courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory

The boldest and largest scale of the land-making machines currently proposed for the delta are sediment diversions. Modelled after earlier hydrological diversions constructed by the Army Corps (Davis Pond, Caernarvon), sediment diversions are physically simple (a concrete outlet in the otherwise continuous levee walls lining the Mississippi, allowing water and sediment to spill out of the main channel during flood events, mimicking the historic rhythm of the floodplain) and extremely cost-efficient. Yet they manage to both be incredibly controversial (unlike precision-guided dredge pipelines, which can transport sediment across farms and infrastructure and backyards, sediment diversions achieve their cost-effectiveness through restoring the cycle of flooding and sediment deposition across wide swathes of land, which in the delta is usually privately-owned and often the property of a single family for generations dating back to French settlement) and require awe-inspiringly complex feats of sedimentary computation.

Will this all work? It’s hard to say. These are early days of experimental approaches to a wicked problem. So far, all approaches to erosion control and balancing the needs of human residents with the tendencies of rivers have led to rather problematic unintended consequences. (This can be expected to continue.) Techniques are improving, but the situation is getting harder at the same time. For Louisiana, there’s the real possibility that even if every last particle coming down the Mississippi were captured and put to work by one of these new land making machines that it wouldn’t be enough. It may well be that too much sediment is trapped upstream behind dams and sea levels may be rising too fast. Louisiana is living in the future and the future isn’t always an easy place to live.

DredgeFest Louisiana runs Jan 11-17 with a public symposium on the 11th & 12th in New Orleans.