As you kick back under a glittering shower of high-production-value pyrotechnics tonight, take a second to remember how the modern firework started out: As a tiny, but startling, accident.

In China, roughly 2200 years ago, the first firework was just a reed of bamboo roasting over a fire. And just like with corn kernels, all of that applied heat caused the air inside the reed to expand. Within minutes, the reed’s thin casing could no longer handle the internal pressure, and — bam! — fireworks. The noise gave the nearby humans such a start, they decided it could be effectively deployed to frighten away evil spirits.

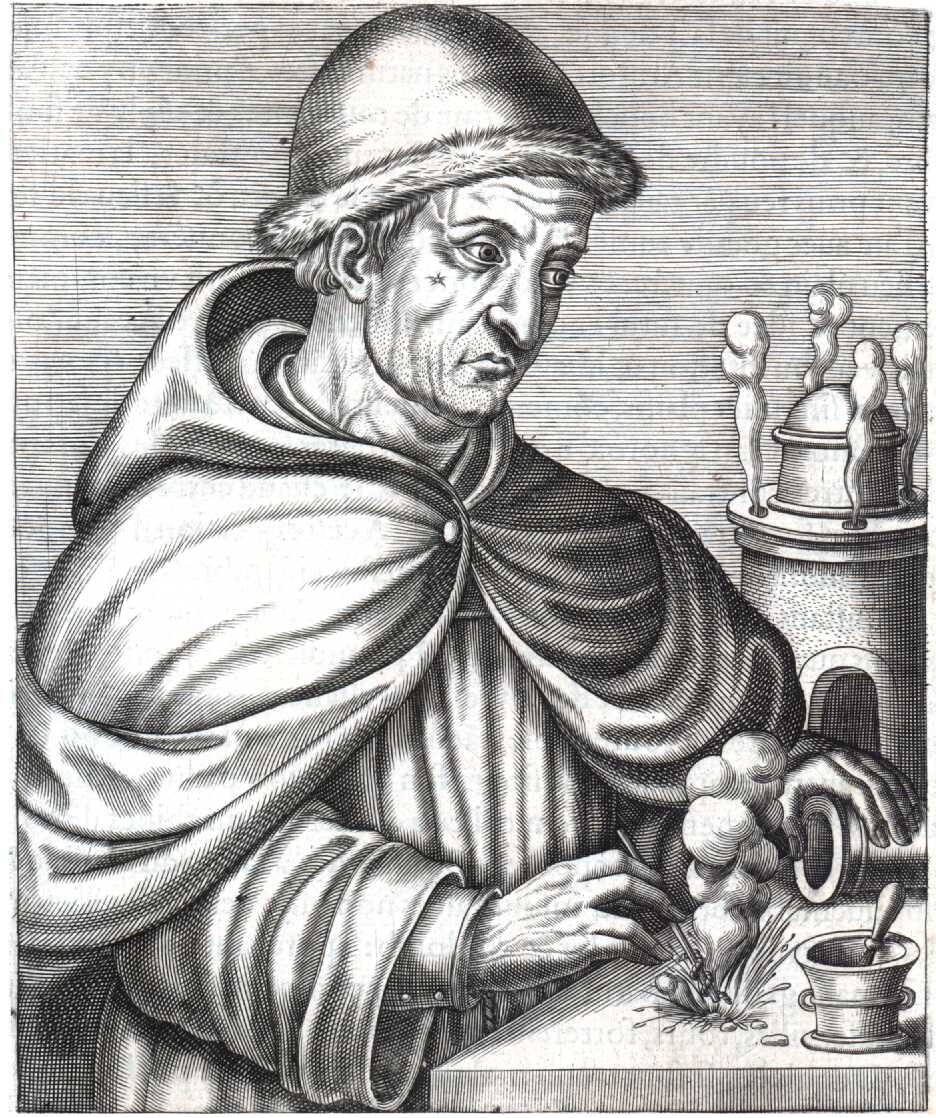

An engraving shows the invention of gunpowder.

In the grand scheme of firework history, barbecued bamboo was more party trick than show stopper. That all changed when the Chinese invented gunpowder, in the 9th century. Tinkering alchemists — who had experimented with saltpeter for years — finally landed on the perfect recipe: 75 per cent saltpeter (potassium nitrate), 15 per cent charcoal, and 10 per cent sulfur (the same ratio is used today). Their discovery held the key to a huge range of inventions — among them, modern fireworks and the multistage rocket.

Naturally, others were eager to get their hands on this explosive technology. In fact, the Mongols were so desperate to learn its secrets, they captured Chinese artisans and forced them to reveal their trade recipes. Ultimately, the Mongols used their knowledge to conquer eastern Europe, where gunpowder was unknown. And just like the invaders who brought it with them, gunpowder soon seemed to be everywhere.

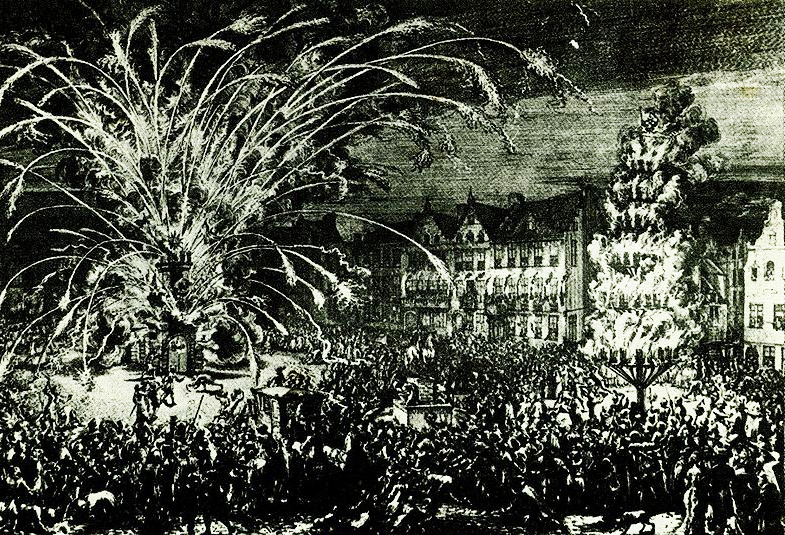

A fireworks celebration, in 1686, in Brussels.

By the 14th century, both the holy festivals taking place at Christian religious sites and the chest-pounding taking place on European battlefields were often punctuated with sprays of gunpowder-fired explosions. Designing and igniting the displays took special skill (and precision), so groups of gunners were created to take on the task. But fireworks still hadn’t become an art. That didn’t happen until 1743, when five Italian brothers named Ruggieri brought this so-called “Chinese fire” to the stage of Paris’ Comédie Italienne.

The Ruggieri brothers could do magical things with a bit of gunpowder. They fixed crosses, polygons, wheels, and stars to iron axles supporting the displays, creating spinning bursts of fire behind the actors. Soon enough, the fireworks were stealing the show — they were even given their own stage names, like “Magical Combat,” “Gardens of Flowers,” “The Palace of Fairies,” and “The Forges of Vulcan.” (Way better names than “Killer Bees,” amirite?) The brothers were born innovators, and their techniques — which focused on creating moving fireworks, rather than stationary ones — upstaged the shot-by-shot deployment of their contemporaries. The trick even earned the brothers an appointment making displays for Louis XV’s court.

A Ruggieri display at the French court.

The promotion was great for the Ruggieri, but it pissed off quite a few pyro-practitioners working locally. Tensions came to a head in 1749, when the competing factions got into an argument over which group would service an event. When neither group would step down, they both decided to set their work alight at the same time. What ensued was a disaster of epic proportions: The quarrel killed 40 people and injured 300.

An illustration of the Ruggieri fireworks show, which Handel scored with Music for the Royal Fireworks.

The Ruggieri endured in the courts, though — in 1750, Georg Friedrich Handel even composed a Music for the Royal Fireworks to accompany one of their displays. Yet the intensity of the Ruggieri pyrotechnics would prove deadly more than once. In 1770, during Marie Antoinette’s nuptials, Petroni Ruggieri lit up a celebratory display that spooked the crowd. The huge group onlookers quickly transformed into a freaked-out mob, and several people were trampled to death. The Ruggieri, it seemed, were done for.

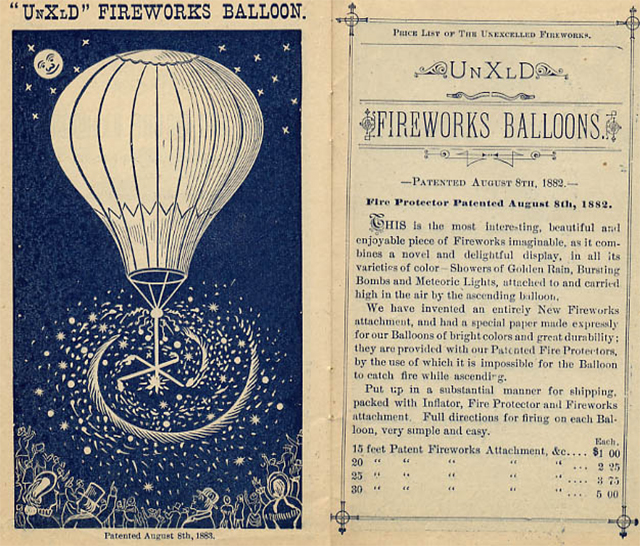

How do you stage a comeback when you’re out of favour with the court? With science — and no small amount of flair. Claude-Fortuné Ruggieri, a member of the Ruggieri family’s next generation of pyro-artists, grew up around modern chemistry — and he put this new knowledge to use in the family business. Even compared to his wild predecessors, Claude-Fortuné was a modernist, experimenting with oxygen and phosphorus and igniting his displays from hot air balloons. But his biggest contribution to his field were the special metallic salts that he engineered to manipulate colour. By adding a dash to other active ingredients, Ruggieri found that he could turn a flame green. And if he added a combination of chlorinated powder and strontium, he could create red, barium green, and copper blue.

A brochure from the Unexcelled Fireworks Company, from 1887, sold items like the balloon-based fireworks seen above. Image via.

Thanks to Claude-Fortuné’s chemical know-how, the modern firework had been born. By the end of the 18th century, fireworks were being used for celebrations all over the world. They took on special important in fledgling America, when John Adams requested a special display to mark the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The basic recipe for fireworks hasn’t changed much since Adams’ day, though pyrotechnicians have improved the control and intensity of modern-day displays.

At-home fireworks were sold in the US beginning in the early 20th century. Image via.

In the US, Baseball became synonymous with fireworks in 1909, thanks to the Pittsburgh Pirates’ owner Barney Dreyfuss. Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field had opened just a few days before, and Dreyfuss requested the team’s doubleheader end with a grand display of patriotic explosions for the 40,000 attending fans. The display was a huge hit — the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette even called it “the altar upon which the marriage of baseball and fireworks was consummated.”

For the fans’ sake, lets hope they used protection.

Lead image, “Fireworks in Naples” by Oswald Achenbachm in 1975, from the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.