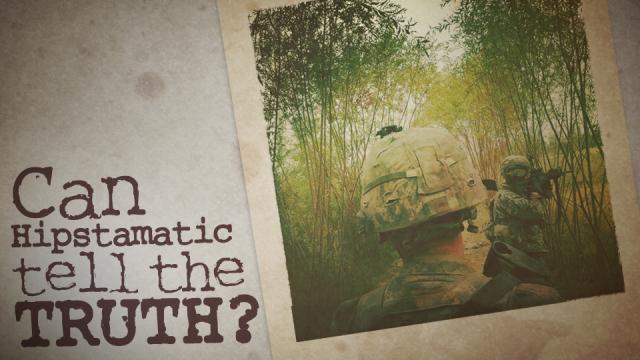

Pictures of the Year International is a photojournalism contest that’s a pretty big deal. This photo by New York Times photographer Damon Winter of the 2nd Platoon under fire in Afghanistan took third place this year. It was taken with the iPhone app Hipstamatic, which slathers photos with moody effects.

The fauxlaroids produced by Hipstamaddicts and Instagrammers are semi-controversial enough when they’re just throwaway snaps of everyday life, spewed hourly or daily by regular folk – TV-dinner art – but what about when these tinted, tilt-shifted and vignetted photos are the artifacts of photojournalism, photography that ostensibly tries to tell a truth? Like photos of war.

Chip Litherland, who’s shot for the NYT, WSJ and others, says of the winning Hipstaprint:

The fact it was shot on a phone isn’t relevant at all and fair game, but what is relevant is the fact it was processed through an app that changes what was there when he shot them. It’s now no longer photojournalism, but photography.

When a Reuters photographer altered a photo to make the aftermath of an Air Force bombing on the Lebanese capital of Beirut look more dramatic and devastating by adding more smoke billowing over the city, it was unquestionably not photojournalism. It was deceit.

The Times is no stranger to the debate of where the line between image “manipulation” and “enhancement” exactly falls, either. Here’s the Times ‘ official policy on image manipulation:

Images in our pages, in the paper or on the Web, that purport to depict reality must be genuine in every way. No people or objects may be added, rearranged, reversed, distorted or removed from a scene (except for the recognised practice of cropping to omit extraneous outer portions).

[Emphasis mine.]

Hipstamatic generates an atmosphere, an aesthetic that ostensibly doesn’t exist in reality. Our vision only tends to resemble 1970s photography when our minds are lubricated with pharmaceutical enhancements, after all. Is it photojournalism when an image is deliberately changed to heighten or affect mood that we literally can’t see with our eyes for the sake of aesthetics and emotion? Is the definition of reality here merely confined to the collection of objects depicted in the photograph?

Staring at the photo in question, “A Grunt’s Life”, I can see how the photographer – the person who was there, documenting a moment in a time – can reasonably argue that his Hipstamatic print more accurately depicts the feeling of what it was like to be there than if he had simply taken a conventional, straightforward photograph. A photo that, from a certain point of view, is perhaps more truthful.

I suspect the unease over its authenticity as an article of photojournalism comes precisely from the ease and deliberateness with which the effect is applied. The more convenient something is, the more fake it feels. Manipulating the mood of a photo in a dark room, toying with the way it looks to provoke a particular emotional response using chemicals probably wouldn’t provoke this kind of response. Nor would simply using an older camera that happened to produce that kind of image. It’s analogue, so by definition it’s authentic, the logic goes.

Either way, there’s no turning back. Winter might be the first photojournalist to use a slick photo app to document an event, but he won’t be the last.

[POYI via Chip Litherland, Original Image: Damon Winter/NYT]